Birdfinding.info ⇒ Short-eared Owls are generally uncommon and localized across their enormous near-global range. The widespread “Northern” form breeds in tundra and other grasslands, mainly in remote areas, and winters in low-lying grasslands and marshes, often along lakeshores and coasts. The “Hawaiian” form is locally conspicuous in uplands of Maui and the Big Island. The “Antillean” form is very localized on Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, and Cuba; and strays regularly to the Florida Keys in late spring. The “Southern” form is fairly common in Argentina and portions of southern Chile and south-central Brazil, and very localized in the central and northern Andes.

Short-eared Owl

Asio flammeus

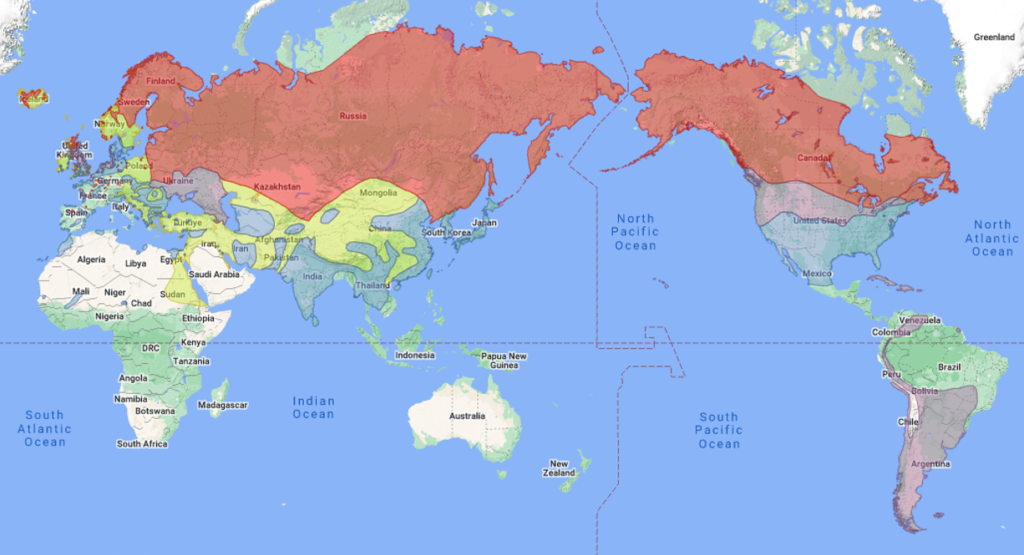

Widespread in the Northern Hemisphere: breeds on arctic and temperate plains and winters in temperate and tropical grasslands. Nonmigratory populations are found in Hawaii, the West Indies, and South America.

Approximate distribution of the Short-eared Owl. © Xeno-Canto 2023

Comprises three or four potentially distinct forms:

“Northern Short-eared Owl” (flammeus): Eurasia and North America; highly migratory.

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl” (sandwichensis): resident in the main Hawaiian Islands; apparently indistinguishable from “Northern”.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl” (domingensis): resident in the Greater Antilles.

“Southern Short-eared Owl” (suinda): South America; largely resident, but seasonally dispersive.

Breeding. The “Northern” form breeds on tundra, prairies, steppes, and marshlands across Eurasia and North America, mostly at high latitudes, but also south locally into the southern temperate zone.

In Eurasia, it breeds from Iceland, Great Britain, and northern continental Europe east across Scandinavia and nearly throughout the Russian Federation to the Bering Sea, south locally to central Spain, Serbia, eastern Turkey, the Caucasus, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Heilongjiang, and Sakhalin.

Breeding Bird Survey Abundance Map: Short-eared Owl. U.S. Geological Survey 2015

In North America, it breeds nearly throughout Alaska east across Canada to Newfoundland, north to southern and central portions of the Arctic Archipelago, and south to the Great Basin and the northern Great Plains; very locally south to southern California, the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence Valley, and Nova Scotia.

Nonbreeding. The “Northern” form winters in southern portions of breeding range and significantly farther south into the tropics.

In Eurasia, it winters north to Scotland, southern Scandinavia, western Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Heilongjiang, and Hokkaido, and south to the Senegal, Ethiopia, Oman, southern India, Thailand, and southeastern China (to Zhejiang).

In North America, it winters from south-coastal Alaska and southern Canada south to northern Mexico and the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida. Winters sparingly south to Baja California Sur, the Mexico City area, and southern Veracruz.

Nonbreeding. The “Northern” form winters in southern portions of breeding range and significantly farther south into the tropics.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, blending into its surroundings on its snowy, temperate wintering grounds. (Howe, Idaho; December 31, 2016.) © Darren Clark

In Eurasia, it winters north to Scotland, southern Scandinavia, western Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Heilongjiang, and Hokkaido, and south to the Senegal, Ethiopia, Oman, southern India, Thailand, and southeastern China (to Zhejiang).

In North America, it winters from south-coastal Alaska and southern Canada south to northern Mexico and the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida. Winters sparingly south to Baja California Sur, the Mexico City area, and southern Veracruz.

Movements. The “Northern” form is among the most migratory of owls, the only one that regularly migrates from the arctic to the tropics, and the only one that regularly strays over the open ocean.

Somewhat regular as a transoceanic vagrant to several remote island groups, including Bermuda, the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the Northwest Chain of Hawaii—and presumably also to the main Hawaiian Islands where it would be indistinguishable from the resident “Hawaiian” form.

The putative subspecies ponapensis of Pohnpei in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia is often regarded as an established taxon, but that island appears too small to support a viable population so the Short-eared Owls there seem likely to be vagrant “Northerns” that arrived accidentally and were able to survive.

Winter vagrants have been recorded south to Guatemala, Nicaragua, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and Johnston Atoll.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, blending into its surroundings on its tropical wintering grounds. (Banni Grassland, Kachchh, Gujarat, India; December 19, 2017.) © Savio Fonseca

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl”. Endemic to Hawaii, where it is resident on all eight of the major islands from Niihau to the Big Island, where it occurs in all open habitats with sufficient ground cover for roosting.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl”. Local resident of the Greater Antilles: Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and their satellites, including the Isle of Youth, Vieques, and Culebra.

Found at low densities in suitable habitat: scrubby grassland without excessive disturbance, usually near marshes or other waterbodies. Dispersive or partly nomadic within its normal range.

Occurs as a semi-regular wanderer to Florida (exceptionally to Georgia), the Bahamas, and the Cayman Islands. Most or all such birds have been found in spring and summer, evidently dispersing from Cuba after the breeding season.

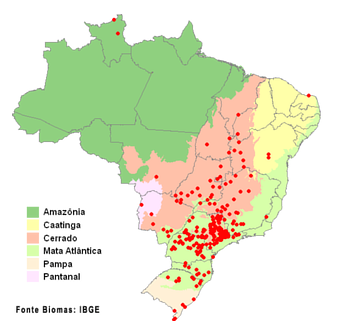

“Southern Short-eared Owl”. Occurs locally in several regions of South America, but inexplicably absent or scarce in many areas of extensive, apparently suitable habitat.

In the north, it is resident in the Andes of central Colombia and disjunctively in the Andes of Ecuador and southwestern Colombia, mainly at elevations of ~2,500-4,000 m.

Brazilian records of the “Southern Short-eared Owl”, by municipality. © WikiAves 2023

It is occasionally detected in the Llanos of Colombia and western Venezuela, and in the grasslands of Roraima and western Guyana, but the scarcity of records suggests that it is not permanently established in these areas.

In the center-west, it is rare and local in wetlands along the coast from Lambayeque to Tacna, and in the Andes of Cajamarca, Junín, Ayacucho, Cuzco, Puno, La Paz, and Cochabamba. Whether it is a resident or occasional visitor in many of these areas remains unclear.

In the east and south, it occurs more or less contiguously from central Chile, northern Argentina (Jujuy), and the Brazilian cerrado (north to southern Mato Grosso and southern Piauí) south to Tierra del Fuego. Within this area, its main centers of abundance are: south-central Chile; southern Patagonia; the pampas of central and eastern Argentina; and south-central Brazil (São Paulo and Paraná).

Also occurs on the Falkland Islands and Juan Fernández Islands (at least on Isla Robinson Crusoe and Santa Clara). Its status on the latter islands is unclear in light of their remoteness and small land area—seemingly too small to support an owl population and too remote for regular inflow from mainland populations.

Southern populations appear to be partly sedentary and partly migratory or dispersive. Vagrants have been recorded from Trinidad, Barbados, and Rio Grande do Norte. Its apparently sporadic occurrence in several areas (e.g., the Llanos, Roraima, Guyana, the Peruvian coastal plain, and the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes) may be the result of dispersal or migration from well-established population centers farther south.

Identification

Distinctive: an open-country owl that often hunts on the wing, flying low over grasslands and marshes, with a meandering, harrier-like flight pattern that alternates between deep, floppy wingbeats and long glides. It also hunts while stationary, perched on top of a bush or fencepost, watching and waiting, then swooping down onto its prey. Largely diurnal, but also active at night and most active around dusk.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, an individual with boldly contrasting black and white upperparts (Avon, New York; March 11, 2018.) © Josh Ketry

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, a relatively pale individual with mostly warm-brown upperparts. (Etzikom, Alberta; July 13, 2016.) © Brian Hoffe

The two apparently divergent forms (possibly separate species) are discussed briefly below and in more detail on separate pages: “Antillean” of the West Indies; and “Southern” of Panama and Costa Rica. The widespread “Northern” form and closely related “Hawaiian” form appear to be indistinguishable.

Short-eared Owls are named for an inconspicuous feature: two short tufts on the crown that are sometimes raised but often lie flat.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, a dark individual showing mostly blackish upperparts, lacking a distinct frame around the facial disk; and with short tufts on the crown raised. (Little Rann of Kutch, Kachchh, Gujarat, India; October 29, 2017.) © Bhaarat Vyas

The plumage is mainly dark-brown and whitish. The upperparts are mostly dark-brown with pale spots; and the underparts are mostly whitish with dark-brown streaks.

The streaking on the underparts is dense and thick on the chest, becoming progressively sparser on the lower breast and belly.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, showing typical underparts pattern: heavy streaking on the chest that becomes progressively sparser on the belly. (North Grand Pré, Nova Scotia; January 20, 2022.) © Guy Stevens

Sometimes shows a distinct facial disk and sometimes not. Some individuals show a distinct contrasting white frame, some have a thin blackish frame, and some have no discernible frame.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, a buffy-brown individual that lacks a distinct facial disk. (Lillooet, British Columbia; October 1, 2008.) © Ian Routley

The eyes are vivid amber-yellow surrounded by black feathers.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, showing distinct white-framed facial disk. (Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Reserve, Juneau, Alaska; November 9, 2022.) © Nathan Kelley

In flight, the upperside of the wing appears mostly brown with large buffy patch in the primaries.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, dorsal view in flight, showing mostly brownish upperwings with buffy windows in the primaries. (Gratiot-Saginaw State Game Area, Michigan; January 1, 2017.) © Darlene Friedman

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, in flight, showing mostly pale underwings with dark-brown crescents on the primaries. (Bear Run Mine, Sullivan County, Indiana; January 2, 2023.) © Ryan Sanderson

The underside of the wing is mostly pale with a prominent black crescent at the base of the primaries. Typically shows one or two additional dark crescents near the tips of the primaries.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl”. Very similar to the widespread “Northern” form, but darker overall, more solid brown above, and buffier below. Unlike most “Northerns”, “Antillean” consistently shows a dark frame around its facial disk.

Structurally, “Antillean” differs from “Northern” in having slightly shorter wings and tail, and significantly (~20%) longer legs, but these differences are not likely to be discernible in the field.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis— note dark brown upperparts with buffy spots and fine streaks on buffy belly. (Bodden Town, Grand Cayman; December 29, 2016.) © Denny Swaby

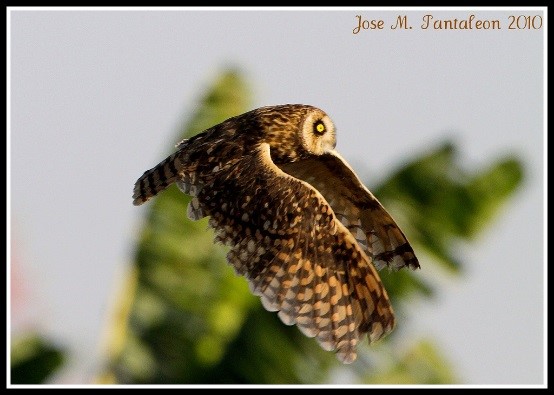

In flight, the upperside of the wing appears mostly brown with a large buffy or cinnamon patch in the primaries.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, showing cinnamon patch in the primaries. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; April 3, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Southern Short-eared Owl”. The plumage patterns and coloration of the “Southern” form are roughly intermediate between the “Northern” and “Antillean” forms.

Like the “Antillean” form, “Southern” typically shows dark-brown upperparts with buffy spots, buffy underparts, and a distinct dark frame around its facial disk.

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda (or possibly pallidicaudus—if this is a valid taxon, which seems unlikely), showing mostly dark-brown upperparts with buffy spots and a distinct dark frame around its facial disk. (Caroni ricefields, Trinidad; May 30, 2012.) © Nigel Lallsingh

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, showing buffy underparts with fine streaks on the belly and contrasting white crescents at the outer edge of the facial disk. (Americana, São Paulo, Brazil; June 19, 2013.) © Rosemari Julio

Like the “Northern” form, many “Southerns” also have contrasting white crescents at the outer edge of the facial disk. On some individuals the frame is predominantly white.

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, dorsal view in flight showing buffy or cinnamon patches in the primaries. (São Sebastião do Paraíso, Minas Gerais, Brazil; December 14, 2014.) © Jose Quintino

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, ventral view in flight showing prominent black crescents at the bases of the primaries. (Americana, São Paulo, Brazil; June 3, 2015.) © Antonio Bordignon

Voice. The “Northern Short-eared Owl” has well-known vocalizations, including hoots, barks, growls, and screeches. The “Hawaiian” form is not known to be vocally distinct from the “Northern”; whereas the “Southern” form may differ significantly (judging from the few publicly available recordings—see below). The voice of the “Antillean” form is not reliably described in available references, and should be studied for similarities to or differences from those of the “Northern” and “Southern” forms: Sometimes the hoots are higher-pitched:Rapid bouts of wing-clapping are often heard:Contact calls include a hoarse, nasal bark or yip with a rising inflection and sudden stop:Sometimes calls in bouts of 2-10 barks that resemble the scolding of a jay:Or soft, low growls given in quick series:Alarm calls include harsh, catlike growls and screeches:

The most frequently recorded vocalizations of the “Southern Short-eared Owl” are nasal barks:

Sometimes calls in bouts of 2-10 barks that resemble the scolding of a jay:

Around the nest, adults sometimes call to one another with a soft, nasal wa-a-ah:

Publicly available recordings of the “Southern” form apparently include no examples of the hooting calls given by “Northern” males. (Hypothetically, if this call is truly absent from the “Southern” form’s repertoire, then that would seem to be a significant factor in assessing its divergence from the other forms.) Isolated hoots have been recorded:

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of up to ten recognized subspecies, subdivided into three to five potentially distinct forms: “Northern” (flammeus); “Southern” (suinda plus bogotensis, pallidicaudus, and sanfordi); “Antillean” (domingensis plus portoricensis and cubensis); “Hawaiian” (sandwichensis); and “Pohnpei” (ponapensis).

However, the validity of several of the subspecies is dubious. Ponapensis is known only from a few individuals found on the small Micronesian island of Pohnpei, which is mostly forested and seems unlikely to support a viable population of Short-eared Owls on a long-term basis as would be needed to sustain a distinct taxon. Sandwichensis apparently receives a regular inflow of vagrant flammeus, and is not known to differ from flammeus in any feature. Both of these tropical Pacific subspecies appear to be recent arrivals, and ponapensis seems inherently ephemeral—which would likely disqualify it from subspecies status.

The three “Antillean” subspecies appear essentially indistinguishable from one another and show a tendency to disperse between islands, which suggests that they effectively form a single population and lack the genetic isolation that would justify treatment as multiple subspecies. In northern South America, pallidicaudus appear to consist of occasionally wanderers from the Andes or Brazil rather than an established population. Meanwhile, in the Falkland Islands, sanfordi may also be an artifact of semi-regular vagrancy.

Traditionally regarded as conspecific with the Galápagos Short-eared Owl (galapagoensis), which is provisionally treated as a separate species here because both of the recent guidebooks to the owls of the world, König and Weick (2008) and Mikkola (2017), recognize it as such. Their principal bases for distinguishing galapagoensis from flammeus are its apparent genetic isolation and differences in voice, plumage, wing-length, and ecology—among these factors, voice appears to be the most persuasive in light of its importance to owls in general. This is a close judgment call that could go either way.

More Images of the Short-eared Owl

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, holding a rodent in its bill. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; December 18, 2009.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, holding a rodent in its talons. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; December 18, 2009.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda. (Americana, São Paulo, Brazil; April 14, 2018.) © Cristiane Stubing

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, with atypically uniform brown upperparts. (El Milagro, La Libertad, Peru; October 16, 2018.) © Cliff Cordy

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda. (Uquisilla, Puno, Peru; June 13, 2015.) © Ronald Hinojosa Cardenas

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, a relatively dark individual with a distinct white-framed facial disk. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; March 25, 2019.) © Jan Thom

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, showing dark brown upperparts with buffy spots. (Bodden Town, Grand Cayman; December 29, 2016.) © Denny Swaby

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; December 4, 2019.) © William Richards

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, in weak light, but showing dark upperparts with buffy spots. (Dominican Republic.) © Pedro Genaro Rodríguez

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; August 28, 2017.) © Michael Bolte

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, showing dark brown upperparts with buffy spots. (Dominican Republic; July 30, 2016.) © Timoteo Estévez

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Kawaiele State Waterbird Sanctuary, Kauai, Hawaii; September 22, 2017.) © Patrick Baglee

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Hawaii Belt Road, Big Island, Hawaii; May 19, 2015.) © Darren Dowell

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Miki Road, Lanai, Hawaii; April 20, 2006.) © Michael Walther

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, typically indistinguishable from the “Northern” form. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; May 26, 2017.) © Rudy Nuissl

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, a relatively dark-brown individual showing short ear-tufts on the crown partly raised. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; January 1, 2020.) © David McQuade

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis—note fine streaks on buffy belly. (Cabo Rojo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico; September 21, 2012.) © Michael J. Morel

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. sanfordi. (Kidney Island, Falkland Islands; February 19, 2006.) © Alan Henry

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, showing dark brown upperparts with buffy spots. (Dominican Republic; January 31, 2013.) © Mario Dávalos P.

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Maui, Hawaii; February 25, 2017.) © Mark Salvidge

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Old Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2019.) © Michael Bolte

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waimea Canyon, Kauai, Hawaii; March 20, 2019.) © Barry Langdon-Lassagne

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, ventral view showing streaking on the underparts. (Coyhaique, Aisén del General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, Chile; September 22, 2017.) © Juan Pastor Medina Avilés

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; March 28, 2018.) © Bill Lisowsky

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i, Big Island, Hawaii; January 23, 2020.) © Christopher Escott

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, showing typical underparts pattern: heavy streaking on the chest that becomes progressively sparser on the belly. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; April 12, 2020.) © Sherman Wing

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; August 28, 2017.) © Michael Bolte

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; April 27, 2019.) © Lizabeth Southworth

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; June 5, 2016.) © Michael Bolte

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Old Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2019.) © Michael Bolte

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, holding a rodent in its bill. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; December 18, 2009.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, with short ear-tufts on the crown raised. (Golf Dorval, Pointe-Claire, Quebec; February 23, 2019.) © Daniel Jauvin

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, facial close-up showing whitish coloration in the border of the facial disk. (Americana, São Paulo, Brazil; April 3, 2019.) © Marcelo Figueiroa

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis. (Dominican Republic.) © Miguel A. Landestoy T.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis, showing fine streaks on buffy belly. (Jekyll Island, Georgia; May 17, 2019.) © Ian Morrison

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, dorsal view in flight showing the large buffy patch in the primaries. (São Roque de Minas, Minas Gerais, Brazil; March 19, 2013.) © Fabio Rage

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, an exceptionally dark brown and buffy individual. (Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary, Lincoln Park, Chicago, Illinois; November 12, 2022.) © Matt Zuro

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis—note dark crescents on the underwing. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; April 3, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; April 3, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; April 3, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; April 3, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Antillean Short-eared Owl,” A. f. domingensis. (San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic; January 20, 2010.) © José M. Pantaleon I.

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, dorsal view in flight, showing mostly brownish upperwings with buffy windows in the primaries. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; November 17, 2019.) © Patrick Vaughan

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; January 21, 2020.) © Richard Pollard

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, a relatively pale-brown individual in flight. (Hosmer Grove, Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii; October 15, 2017.) © Sharif Uddin

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; February 5, 2020.) © Kent Forward

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Saddle Road, Big Island, Hawaii; April 27, 2019.) © Lizabeth Southworth

“Southern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. suinda, ventral view in flight showing the prominent black crescents at the bases of the primaries. (Americana, São Paulo, Brazil; June 14, 2014.) © Rogério Machado

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis, ventral view in flight, showing mostly pale underwings with dark-brown crescents on the primaries. (Waiki’i Ranch, Big Island, Hawaii; February 26, 2014.) © Doug Cooper

“Hawaiian Short-eared Owl,” A. f. sandwichensis. (Hosmer Grove, Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii; July 18, 2018.) © Chris Rohrer

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus, ventral view in flight, showing mostly pale underwings with dark-brown crescents on the primaries. (Kyle, Saskatchewan; March 9, 2017.) © Nick Saunders

“Northern Short-eared Owl”, A. f. flammeus. (Avon, New York; January 7, 2018.) © Josh Ketry

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2021. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Third Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2021. Asio flammeus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T22689531A202226582. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22689531A202226582.en. (Accessed July 6, 2023.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

de la Peña, M.R., and M. Rumboll. 1998. Birds of Southern South America and Antarctica. Princeton University Press.

Denny, J. 2010. A Photographic Guide to the Birds of Hawai’i: The Main Islands and Offshore Waters. University of Hawai’i Press.

eBird. 2023. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed July 6, 2023.)

Enríquez, P.L., K. Eisermann, H. Mikkola, and J.C. Motta-Junior. 2017. A Review of the Systematics of Neotropical Owls (Strigiformes). In Neotropical Owls: Diversity and Conservation (P.L. Enríquez, ed.). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland.

Erize, F., J.R. Rodriguez Mata, and M. Rumboll. 2006. Birds of South America: Non-Passerines: Rheas to Woodpeckers. Princeton University Press.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Garrido, O.H, and A. Kirkconnell. 2000. Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Gemmill, D. 2015. Birds of Vieques Island, Puerto Rico: status, abundance, and conservation. Special issue of The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology.

Hoffmann, W., G.E. Woolfenden, and P.W. Smith. 1999. Antillean Short-eared Owls Invade Southern Florida. Wilson Bulletin 111:303-313.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

iNaturalist. 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/. (Accessed July 6, 2023.)

Kenefick, M., R. Restall, and F. Hayes. 2008. Field Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago. Yale University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

König, C., and F. Weick. 2008. Owls of the World (Second Edition). Yale University Press.

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Martínez Piña, D.E., and G.E. González Cifuentes. 2021. Field Guide to the Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mikkola, H. 2017. Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide: Second Edition. Firefly Books, London.

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Raffaele, H. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Redman, R., T. Stevenson, T., and J. Fanshawe. 2009. Birds of the Horn of Africa: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Socotra. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Salt, W.R., and J.R. Salt. 1976. The Birds of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Wikiaves. 2023. Mocho-dos-banhados, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/mocho-dos-banhados. (Accessed July 6, 2023.)

Xeno-Canto. 2023. Short-eared Owl – Asio flammeus. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Asio-flammeus. (Accessed July 6, 2023.)