Birdfinding.info ⇒ Fairly common in some portions of its enormous range; scarce or localized in other areas. Regions where it is generally numerous include the western U.S. from Oregon and California to Texas and south through most of Mexico, and eastern South America from central Brazil to central Argentina. (For the potentially distinct, localized West Indian forms, see “White-winged Barn Owl”, “Curaçao Barn Owl”, and “Bonaire Barn Owl”.)

American Barn Owl

Tyto furcata

Temperate and tropical Americas from southern Canada to Tierra del Fuego.

Approximate distribution of the American Barn Owl. © Xeno-Canto 2023

Comprises four potentially distinct forms: the widespread “American Barn Owl” (tuidara plus pratincola, guatemalae, bondi, hellmayri, and contempta) and three localized West Indian forms (which are covered separately on their own pages): the “White-winged Barn Owl” (furcata), of Cuba, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands; the “Curaçao Barn Owl” (bargei), of Curaçao; and the “Bonaire Barn Owl” (ssp. nova), of Bonaire.

In North America, resident from southwestern British Columbia, Idaho, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey southward. In summer, small numbers move north to breed, sporadically reaching as far north as the southern Prairie Provinces, southern Quebec, and the Maritimes. A small portion of the northerly wanderers typically remain to overwinter.

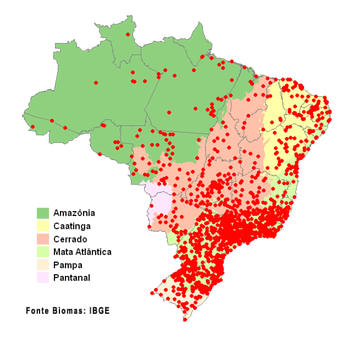

Brazilian records of the American Barn Owl, by municipality. © WikiAves 2023

In Middle America, resident throughout Mexico and Central America, and on a few Caribbean islands: the northern Bahamas; Hispaniola; Cozumel; the Honduran Bay Islands Roatán and Guanaja; and Panama’s Pearl Islands. Also wanders somewhat regularly as a vagrant to Bermuda.

In South America, resident essentially throughout the continent from lowlands up to approximately 4,000 m, but highly localized in the Amazon Basin, which it appears to be colonizing in response to deforestation. Also resident on many adjacent islands, including Isla Margarita (Venezuela), Trinidad, Tobago, Chiloé (Chile), Tierra del Fuego, and the Falkland Islands.

Introduced populations are well established on all of the main Hawaiian Islands and Lord Howe Island (Australia).

Identification

As the only barn owl across most of its range, the American Barn Owl is readily identifiable if seen well. Distinctive features include a heart-shaped facial disk, pale underparts, and blotchy tan, brown, and gray upperparts.

American Barn Owl, showing upperparts with typical patches of grayish, buffy, rusty, and pale-brown and both white and blackish spots. (Juazeiro, Bahia, Brazil; March 31, 2022.) © Nathália Diniz

Like all barn owls, its facial disk has a strongly defined border that is indented on the forehead. When resting, it pinches its facial disk inward, creating a vertical ridge from the forehead to the bill with a furrow on either side.

American Barn Owl with facial disk pinched inward while resting. (Portal, Arizona; August 24, 2018.) © Eric Heisey

The coloration of the plumage varies somewhat—as in other barn owls, males are generally paler than females.

The upperparts typically appear brown at a distance, but close study reveals a mix of grayish patches with white spots and buffy or rusty patches with black spots. The folded wings typically appear pale brown with dark spots.

American Barn Owl, likely female with heavily speckled buffy underparts and mostly dark upperparts. (Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazil; January 14, 2015.) © Marcelo Camacho

Some individuals show almost uniformly dark upperparts, including the folded wings.

The underparts coloration varies from pure white in some males to rich orangish buff in some females. Most individuals show noticeable speckling over some or all of the underparts.

American Barn Owl, buffy female and white male with limited speckling. (Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; September 18, 2015.) © Arthur Goulart

American Barn Owl, dorsal view in flight, showing pronounced blackish bands on the tail and flight feathers. (Farmington Bay Wildlife Management Area, Utah; January 6, 2017.) © Jerry Liguori

When viewed in flight, the uppersides of the spread wings and tail typically appear buffy or whitish overall, with pronounced blackish bands.

American Barn Owl, ventral view in flight, showing ghostly-white appearance, typical of sightings at night. (São Manuel, São Paulo, Brazil; May 14, 2021.) © João Salvador

The undersides of the wings and tail typically appear strikingly white, sometimes with faint bands that are barely visible under most viewing conditions.

“White-winged Barn Owl”. The Greater Antillean endemic form, inhabiting Cuba, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands, typically shows extensively white or buffy wings and tail—i.e., both undersides and uppersides. It averages somewhat larger than the widespread “American Barn Owl” and often appears differently proportioned, with a smaller-looking head and larger body and wings.

“White-winged Barn Owl,” T. f. furcata. (Green Castle Estate, Jamaica; November 5, 2013.) © Alan Van Norman

The coloration of the wings and tail is often distinctive, but variable. On most individuals, the uppersides of the flight feathers and tail are mostly whitish or pale buffy with gray spots—but on some males, all the flight and tail feathers can appear pure white.

On some individuals—presumably females—the flight and tail feathers can appear mostly buffy with large dark spots, making them visually indistinguishable from the widespread “American Barn Owl” (which occurs at least occasionally in Cuba).

“White-winged Barn Owl,” T. f. furcata, presumptive male with pure white secondaries. (Remedios, Villa Clara, Cuba; January 19, 2016.) © Michael J. Good

“White-winged Barn Owl,” T. f. furcata, likely female. (Anchovy Gardens, Jamaica; March 28, 2023.) © Emily Hjalmarson

“Curaçao Barn Owl”. The Curaçao endemic form is an undescribed subspecies with a tiny population, and is the only owl known from Bonaire. Based on the single specimen that has been measured, it is distinctly smaller than all other populations of American Barn Owl, including the population on Bonaire, 20 miles east of Curaçao.

The “Curaçao Barn Owl” is probably not visually differentiable from continental populations, but is substantially smaller: with measurements ~75-80% as large. Judging from the few published photos, it tends to have largely gray-brown upperparts and black-speckled white underparts, making its plumage more contrasty than on most American Barn Owls.

“Curaçao Barn Owl”, T. f. bargei, a pair showing gray-brown upperparts and black-speckled white underparts. © Peter van der Wolf

“Bonaire Barn Owl”. The Bonaire endemic form is an undescribed subspecies with a tiny population, and is the only owl known from Bonaire. Based on the single specimen that has been measured, it is distinctly smaller than all other populations of American Barn Owl, but distinctly larger than the barn owls on Curaçao, 20 miles west of Bonaire.

The “Bonaire Barn Owl” is probably not visually differentiable from continental populations. Judging from the few published photos, it tends to have largely gray-brown upperparts and black-speckled white underparts, making its plumage more contrasty than on most American Barn Owls. Some individuals, presumably females, appear darker overall, with warm-brown upperparts and a buffy wash on the head and underparts.

“Bonaire Barn Owl”, T. f. ssp. nova, a pair showing gray-brown upperparts and black-speckled white underparts. (Washikemba, Bonaire; April 17, 2023.) © Susan Davis

Voice. The most typical call is an abrupt, harsh rasp (like rough sandpaper scraping metal), often repeated frequently and at length:Sometimes more excited and given in a rapid series:The male’s territorial call is a harsh scream, often given in flight, repeated irregularly:The varied repertoire also includes excited metallic clinking and rattling:Alarm calls are often long, drawn-out rasps or hisses:Calls of the “White-winged Barn Owl” are similar, but judging from the publicly accessible recordings, appear to be somewhat softer and less harsh than the corresponding calls of the widespread “American Barn Owl”. The typical call is a soft rasp (sandpapery scraping noise), often repeated frequently and at length:

The male “White-winged’s” territorial scream appears clearer than that of the continental form’s equivalent call (at least, it does in this recording):

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of eight or nine recognized and one undescribed subspecies that are subdivided into three potentially distinct forms: “White-winged Barn Owl” (furcata, of Cuba, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands, plus the sometimes-recognized niveicauda of the Isle of Youth); “Curaçao Barn Owl” (bargei, of Curaçao); “Bonaire Barn Owl” (ssp. nova, of Bonaire); and the widespread “American Barn Owl” (tuidara plus pratincola, guatemalae, bondi, contempta, and hellmayri).

Three more subspecies are usually regarded as conspecific with the American Barn Owl, but are provisionally recognized here as comprising two separate species: the Galápagos Barn Owl (punctatissima); and the Lesser Antillean Barn Owl (insularis plus the potentially distinct “Dominica Barn Owl”, nigrescens).

Worldwide barn owl taxonomy is unsettled. The American Barn Owl has traditionally been classified together with many Old World taxa as comprising the cosmopolitan Barn Owl, Tyto alba. Many, if not most, taxonomic authorities maintain this classification. However, the emerging consensus is that the traditional T. alba represents three major lineages that should each be recognized as one or more species: the Western Barn Owl (alba) of western Eurasia and Africa; the Eastern Barn Owl (javanica) of southern Asia and Australasia; and the American Barn Owl (furcata) of the New World. Each of these clades includes distinctive insular forms that may be best regarded as separate species. The provisional subdivision of American barn owl taxa outlined here adopts the approach shared by both recent guidebooks to the owls of the world, König and Weick (2008) and Mikkola (2012).

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2021. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Third Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Aliabadian, M., N. Alaei-Kakhki, O. Mirshamsi, V. Nijman, and A. Roulin. 2016. Phylogeny, biogeography, and diversification of barn owls (Aves: Strigiformes). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 119:904-918.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2019. Tyto alba (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22688504A155542941. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22688504A155542941.en. (Accessed September 13, 2023.)

eBird. 2023. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed September 15, 2023.)

Enríquez, P.L., K. Eisermann, H. Mikkola, and J.C. Motta-Junior. 2017. A Review of the Systematics of Neotropical Owls (Strigiformes), Neotropical Owls: Diversity and Conservation (P.L. Enríquez, ed.). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland.

Erize, F., J.R. Rodriguez Mata, and M. Rumboll. 2006. Birds of South America: Non-Passerines: Rheas to Woodpeckers. Princeton University Press.

Fagan, J., and O. Komar. 2016. Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garrigues, R., and R. Dean. 2014. The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (Second Edition). Cornell University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

iNaturalist. 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/. (Accessed September 15, 2023.)

Jaramillo, A. 2003. Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

Kenefick, M., R. Restall, and F. Hayes. 2008. Field Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago. Yale University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

König, C., and F. Weick. 2008. Owls of the World (Second Edition). Yale University Press, New Haven.

Martínez Piña, D.E., and G.E. González Cifuentes. 2021. Field Guide to the Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mikkola, H. 2013. Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide (Second Edition). Firefly Books, London.

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pueo Hui / Hawaiian Short-eared Owl Group, The Barn Owl, https://www.pueoproject.com/other-owl-species-the-barn-owl. (Accessed September 13, 2017.)

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Stiles, F.G., A.F. Skutch, and D. Gardner. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2023. Suindara, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/suindara. (Accessed September 15, 2023.)

Wink, M., P. Heidrich, H. Sauer-Gurth, A. El-Sayed, and J. González. 2008. Molecular phylogeny and systematics of owls (Strigiformes), in Owls of the World (C. König and F. Weick, eds.). Christopher Helm, London.

Xeno-Canto. 2023. American Barn Owl – Tyto furcata. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Tyto-furcata. (Accessed September 15, 2023.)