Birdfinding.info ⇒ A widespread, familiar habitat generalist in North America, where it is present year-round nearly throughout the continent. Common in many areas, but mostly nocturnal, so it is usually found through either effort or luck—often around an active nest or as a deep voice hooting in the distance. In South America it is much less common and much more localized, occurring mainly in open and semi-open landscapes, including the Chaco, Argentine Mesopotamia, southeastern Brazil, and the pampas of Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay.

Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

The Americas from Alaska to Argentina.

Approximate distribution of the Great Horned Owl. © BirdLife International 2018

Resident essentially throughout North America in all types of habitats north to the treeline and south to the southern tip of Baja California and Oaxaca, but absent from humid tropical lowlands south of Colima and Tamaulipas.

East of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, disjunct populations are resident on the Yucatán Peninsula (south to Palenque and northern Belize) and in the highlands from western Chiapas to northwestern Nicaragua—and formerly or sporadically south to central Costa Rica (one recent record: Volcan Irazú National Park; December 27, 2015). Also recently reported from the Mosquitia savanna in northeastern Nicaragua.

Patchily distributed in northern South America, with small populations in five areas: (1) the Caribbean coastal lowlands of Colombia and northwestern Venezuela; (2) the Andes from central Colombia to northern Peru, mainly at elevations of 3200-4500 m; (3) the Llanos of Colombia and western Venezuela; (4) the savannas of Roraima and Guyana; and (5) the Atlantic coastal lowlands from the Orinoco River delta to the Amazon River delta, with some records upriver to the Santarém area.

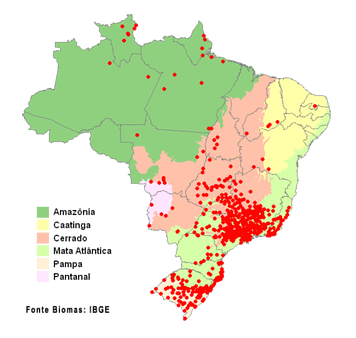

Brazilian records of the Great Horned Owl, by municipality, showing localized distribution, with clusters in the southeast and far south. © WikiAves 2023

In central and eastern South America it occurs mainly in savannas, brushlands, and lightly wooded habitats from easternmost Peru across northern Bolivia, southern Mato Grosso, extreme southeastern Pará, and Tocantins to southern Piauí, western Bahía, and Espírito Santo, south to central Argentina (to Córdoba and Buenos Aires City) and Uruguay.

Occasionally found outside of its principal South American range, including well-documented reports from: the Peruvian Andes (Calipuy National Sanctuary, La Libertad; May 13, 2023); near Iquitos (Maniti, Loreto; January 25, 2009); and far northeastern Brazil (Serra da Formiga; Rio Grande do Norte; November 2, 2018); and scattered records from Brazilian Amazonia.

Identification

A large brown owl with prominent ear-tufts. Widespread, familiar, and readily identifiable as the only “eagle-owl” in most of its range—although it overlaps to some extent in the Peruvian Andes and possibly also northwestern and central Argentina with the slightly smaller, extremely similar Lesser Horned Owl, which is distinguishable mainly by voice.

Great Horned Owl, showing coloration that is typical over much of its range. (Saguenay, Quebec; December 5, 2021.) © Yannick Fleury

Plumage coloration varies regionally and individually. Across most of its range, the typical plumage appears mostly brown overall, with intricately patterned upperparts and boldly barred underparts. The facial disk varies from rufous to gray. The eyes are yellow in most populations, but typically orange in eastern South America.

Great Horned Owl, a relatively pale individual. (Inglewood Bird Sanctuary, Calgary, Alberta; January 11, 2021.) © Ken Pride

The spectrum of typical plumages ranges from pale-gray and white in far northern populations, to blackish overall in the Pacific Northwest, whereas some in the western interior of the U.S. can be sandy-brown. However, relatively blackish, brownish, rusty, and grayish individuals occur to some extent in most populations.

Great Horned Owl, a blackish adult with a nestling. (Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge, Washington; March 7, 2023.) © Brent Angelo

Great Horned Owl, a very pale individual. (Riverwood Park, Fargo, North Dakota; March 18, 2022.) © Dan Mason

Great Horned Owl, a sandy-brown individual. (Chico Basin Ranch, Pueblo, Colorado; September 12, 2021.) © Jim Merritt

Great Horned Owl, a warm-brown individual with the orange eyes typical in eastern South America. (Pinhamondhangaba, São Paulo, Brazil; January 7, 2017.) © Juliano Gomes

The throat feathers are cotton-white, a feature that is often conspicuous when vocalizing and in flight, but subtle or concealed at other times.

Great Horned Owl, a grayish-brown individual, vocalizing and showing its white throat-patch. (Mugaha Marsh, Mackenzie, British Columbia; September 10, 2019.) © Blair Dudeck

Great Horned Owl in flight, showing typical pattern and coloration. (Denver International Airport, Colorado; November 5, 2017.) © Ryan Clear

Often appears distinctly long-winged and hawk-like in flight. The flight feathers show prominent bands above and below. On some individuals, the upperside of the wing shows rich buffy or cinnamon flight feathers.

Great Horned Owl in flight, showing bright-cinnamon flight feathers. (St. Albert, Alberta; February 21, 2021.) © Connor Bowhay

Great Horned Owl in flight, with wings fully outstretched, showing buteo-like profile. (Bruneau, Idaho; October 31, 2015.) © Zak Pohlen

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of fifteen recognized subspecies. Formerly considered conspecific with the Lesser Horned Owl (B. magellanicus).

More Images of the Great Horned Owl

Great Horned Owl, a rusty-brown individual showing the intricate mottling on its upperparts. (Vienna Township, Michigan; September 5, 2017.) © Dennis MacNeill

Great Horned Owl with an angry Fork-tailed Flycatcher onboard. (Mostardas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil; January 21, 2021.) © Kacau Oliveira

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2021. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Third Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2018. Bubo virginianus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T61752071A132039486. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T61752071A132039486.en. (Accessed October 9, 2023.)

eBird. 2023. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed October 9, 2023.)

Erize, F., J.R. Rodriguez Mata, and M. Rumboll. 2006. Birds of South America: Non-Passerines: Rheas to Woodpeckers. Princeton University Press.

Fagan, J., and O. Komar. 2016. Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

iNaturalist. 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/. (Accessed October 9, 2023.)

König, C., and F. Weick. 2008. Owls of the World (Second Edition). Yale University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mikkola, H. 2012. Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide. Firefly Books, London.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Salt, W.R., and J.R. Salt. 1976. The Birds of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Stiles, F.G., A.F. Skutch, and D. Gardner. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wikiaves. 2023. Jacurutu, http://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/jacurutu. (Accessed October 2, 2023.)

Xeno-Canto. 2023. Great Horned Owl – Bubo virginianus. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Bubo-virginianus. (Accessed October 9, 2023.)