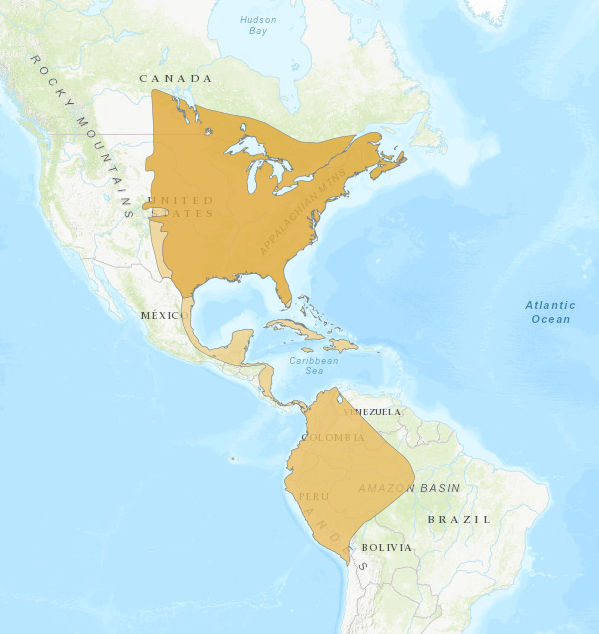

Birdfinding.info ⇒ Very common in summer across much of the central and eastern U.S. and southeastern Canada. From May to August, it is nearly ubiquitous from Nebraska and central Texas to the Eastern Seaboard, and from the Great Lakes and southern New England to the Gulf of Mexico and southern Florida. At other times of year, it can be locally abundant on migration, mainly on coastal plains of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean slope of Central America. From November to February, most of the world’s population presumably retreats to a few favored areas in Ecuador and Peru, though these areas apparently remain undiscovered.

Chimney Swift

Chaetura pelagica

Breeds in eastern North America. Winters in western South America.

Breeding Bird Survey Abundance Map. U.S. Geological Survey 2015

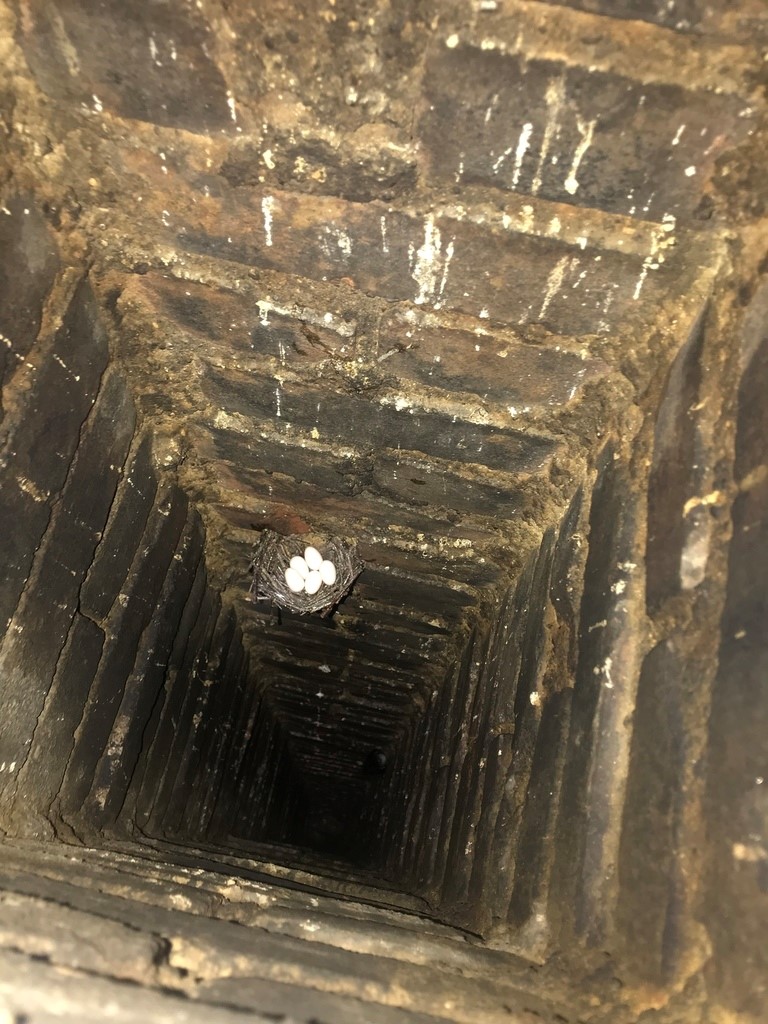

Breeding. Nests semi-colonially in hollow trees and sinkholes, but has adapted to the availability of chimneys, mine shafts, and various types of disused structures. Favors mixed habitats, including agricultural and urban areas.

Breeds across the Great Plains and Acadian forest region from eastern Saskatchewan and central Montana east to Nova Scotia and south to the Rio Grande Valley southern Texas and northeastern Mexico (eastern Coahuila and probably northern Tamaulipas), the Gulf Coast, and southern Florida.

Has also been found or suspected of breeding in California, at least sporadically, at scattered locations along the coast from Mendocino County to San Diego, and in the interior (mainly Owens Valley), but is not known to do so regularly.

Nonbreeding. Wintering grounds are not well known, but the few midwinter records indicate regular presence in the Pacific lowlands of South America from western Ecuador to northern Chile (Arica), intermontane valleys of northern Peru, and western Amazonia from eastern Ecuador to southeastern Peru (and very few confirmed or suspected records from western Brazil).

Movements. Northbound migrants funnel through Panama during February and March and follow the Caribbean slope of Central America and eastern Mexico, arriving in southern Texas during April. Some portion of the population flies directly north from the Yucatán Peninsula across the Gulf of Mexico, but the majority tracks near the western shore. Arrival in most breeding areas occurs during May.

Southbound migration begins in mid-August and by early September very few remain at their breeding sites. Despite near-synchronous departures from the north, their return to the tropics is staggered. Some flocks linger along the Gulf Coast into November, while others have already arrived in South America.

Chimney Swift nest in ventilation shaft. (Wexford, Pennsylvania; June 19, 2019.) © Ken Knapp

Scarce during migration in the West Indies. Fairly regular in April and early May in the Cayman Islands and northern Bahamas—presumably reflecting a portion of northbound migrants straying offshore and finding these outposts. Vagrants are more widespread on fall migration, and have occurred nearly throughout the region.

Often strays across the Atlantic to Bermuda (annually), the Azores, Canary Islands, the British Isles, and the Iberian Peninsula. Most trans-Atlantic records are from late October or early November. A few have appeared in early May.

On the Pacific side, strays annually in April and May to the western states, mostly central and southern California, but several records from northern California and western Oregon. There are several November records from the Galápagos and one June record from the Pribilof Islands (St. Paul, June 16, 1981).

Identification

A mid-sized swift with uniformly dark-brown upperparts and underparts that progress from pale on the throat to darker on the undertail. Usually shows a distinctly darker, blackish mask.

The upperparts are typically more uniform than other Chaetura swifts, but the rump and uppertail are usually slightly paler than the back—on some individuals or in some lighting this contrast appears pronounced (which can cause confusion with other species).

The underparts also vary individually and with lighting and other factors. The throat and chest are usually whitish. The belly and undertail are usually sooty. The mid-section usually blends from pale to dark. However, a few individuals appear all-dark, and a few may appear mostly pale.

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Reeds Lake, East Grand Rapids, Michigan; May 9, 2020.) © Caleb Putnam

Chimney Swift, showing typical blackish mask and gradual shading of underparts from pale to sooty. (Mertzon, Texas; May 31, 2020.) © tvasquez

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Commons Ford Ranch Metro Park, Austin, Texas; May 20, 2020.) © T. Jay Adams

Chimney Swift, showing typically uniform upperparts. (Hutchinson Island, Georgia; June 8, 2017.) © Steve Calver

Chimney Swift, showing typically uniform upperparts. (Lake Erie Bluffs Metropark, North Perry, Ohio; May 12, 2017.) © Karl Bardon

Chimney Swift, showing typically uniform upperparts. (Lake Erie Bluffs Metropark, North Perry, Ohio; May 12, 2017.) © Karl Bardon

Chimney Swift, showing typically weak contrast between dark back and slightly paler rump. (Higbee Beach, Cape May, New Jersey; September 8, 2017.) © Tom Johnson

Chimney Swift, showing typically weak contrast between dark back and slightly paler rump. (Egypt Lane Ponds, Fairhaven, Massachusetts; June 26, 2018.) © Sean Williams

Chimney Swift, showing typically weak contrast between dark back and slightly paler rump. (Blue Heron Nature Reserve, Kent Island, Maryland; May 11, 2020.) © Jonathan Irons

Chimney Swift, showing an atypically pale back and rump. (Sandy Hook, New Jersey; September 9, 2017.) © Jeff Ellerbusch

Chimney Swift, showing an unusually strong contrast between dark back and paler rump. (Higbee Beach, Cape May, New Jersey; September 8, 2017.) © Tom Johnson

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Lakefront Nature Preserve, Cleveland, Ohio; May 5, 2020.) © Gautam Apte

Chimney Swift, showing atypical, mostly uniformly dark underparts with slightly paler throat. (Cape May Point State Park, Cape May, New Jersey; July 19, 2016.) © Tom Johnson

Chimney Swift, showing atypical, uniformly dark underparts. (Higbee Beach, Cape May, New Jersey; September 8, 2017.) © Tom Johnson

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat apparently contrasting with otherwise uniformly sooty underparts. (North English, Iowa; July 22, 2018.) © Dean Hester

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat apparently contrasting with otherwise uniformly sooty underparts. (Lake Erie Bluffs Metropark, North Perry, Ohio; May 12, 2017.) © Karl Bardon

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat, but otherwise uniform underparts in strong light. (Meyer Nature Preserve, Washtenaw County, Michigan; May 9, 2017.) © Brendan Klick

Chimney Swift, brightly illuminated by low-angle light, but showing whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Crowder Road Landing, Tallahassee, Florida; October 31, 2018.) © Jeff O’Connell

Chimney Swift, with mouth open to catch prey. (Reeds Lake, East Grand Rapids, Michigan; May 9, 2020.) © Caleb Putnam

Chimney Swift, showing typical underparts pattern—whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Wheatley, Ontario; May 10, 2019.) © Brandon Holden

Chimney Swift, showing atypical, uniformly dark underparts. (Crescent Beach, St. Johns County, Florida; July 11, 2014.) © Nikolaj Mølgaard Thomsen

Chimney Swift, showing typical underparts pattern—whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Baytown Nature Center, Baytown, Texas; June 16, 2013.) © Greg Page

Chimney Swift, showing typical underparts pattern—whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Onondaga Lake, New York; May 15, 2019.) © Deborah Dohne

Chimney Swift, showing typical underparts pattern—whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Onondaga Lake, New York; May 15, 2019.) © Deborah Dohne

Chimney Swift, molting its secondaries, and showing typical underparts pattern—whitish throat and progressively darker chest, breast, belly, and undertail. (Cape May Point State Park, Cape May, New Jersey; July 20, 2017.) © Tom Johnson

Chimney Swift, showing typically uniform upperparts. (Edwardsville, Illinois; May 22, 2020.) © keemas

Chimney Swift, fledglings beside and in nest. (Tichora Conservancy, Green Lake, Wisconsin; August 8, 2018.) © Thomas Schultz

Chimney Swift, fledglings beside nest. (Tichora Conservancy, Green Lake, Wisconsin; August 12, 2018.) © Thomas Schultz

Chimney Swift, showing whitish throat. (Athens, Georgia; May 29, 2019.) © Katherine Edison

Chimney Swift. (Camdenton, Missouri; August 20, 2018.) © mcartor

Chimney Swift, showing uniformly grayish throat and chest and uniformly dark-brown upperparts. (Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico; June 16, 2019.) © alvaroguardiana

Chimney Swift, showing uniformly grayish throat and chest. (Long Point National Wildlife Area, Ontario; September 4, 2010.) © Mike V.A. Burrell

Cf. Chapman’s and Amazonian Swifts. Chimney Swift’s wintering grounds are not fully understood, but appear to be centered in Peru—from the Pacific lowlands to the Amazon Basin. While in South America, it overlaps with two similar species: Amazonian on its Peruvian wintering grounds and Chapman’s mainly while in transit through Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and to a lesser extent east to Trinidad. None of these species are well-known in the area of overlap: Amazonian and Chapman’s are both rare and mysterious, while Chimney surely visits this region in large numbers, but is rarely detected (except in Panama).

Amazonian, Chapman’s and Chimney are essentially the same size and shape, and would be distinguishable only under favorable viewing conditions. The main difference between Chimney and the others is the underparts: Amazonian and Chapman’s are darker and more uniform below than Chimney.

Conversely, on the upperparts, Amazonian and Chapman’s are paler and more contrasty than Chimney. Both are distinctly paler from the lower back to the uppertail coverts. Chimney usually shows little contrast on the upperparts but under some conditions (perhaps lighting combined with individual variation) it can also show a paler posterior half.

Cf. Sick’s Swift. Chimney and Sick’s Swifts are not known to occur in the same place at the same season, but some portion of both species regularly migrate to Amazonia, so they could potentially overlap. They are essentially the same size and shape, and would be distinguishable only under favorable viewing conditions. Sick’s generally has darker underparts overall and tends to show paler undertail coverts. On the upperparts, Sick’s has paler and more contrasty rump and uppertail coverts than Chimney (i.e., Sick’s resembles Amazonian and Chapman’s Swifts more than Chimney).

Cf. Vaux’s Swift. In central and western North America during summer and especially farther south during migration, Vaux’s and Chimney Swifts may overlap to some extent. Both are Chaetura swifts without strongly distinguishing features, and they are easily confused—although each resembles other species more than they do one another.

Chimney is larger, with longer wings and body, so Vaux’s appears proportionately stumpy-bodied and broad-winged. Chimney typically has almost uniform upperparts, whereas Vaux’s typically shows a noticeably paler rump and uppertail coverts. Finally, Vaux’s gives a wider variety of calls, including some that are either higher-pitched or buzzier than Chimney’s.

Notes

Monotypic species.

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2018. Chaetura pelagica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22686709A131792415. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22686709A131792415.en. (Accessed October 26, 2020.)

Chantler, P. 2000. Swifts: A Guide to the Swifts and Treeswifts of the World (Second Edition). Yale University Press.

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed October 26, 2020.)

Fagan, J., and O. Komar. 2016. Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Garrigues, R., and R. Dean. 2014. The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (Second Edition). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Jaramillo, A. 2003. Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2020. Andorinhão-migrante, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/andorinhao-migrante. (Accessed October 26, 2020.)

Xeno-Canto. 2020. Chimney Swift – Chaetura pelagica. https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Chaetura-pelagica. (Accessed October 26, 2020.)