Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common and conspicuous across much of its large range: e.g., the coastal plains around the Gulf of Mexico, throughout the West Indies, the Pacific lowlands of California, Mexico, Ecuador, and Peru, and across most of eastern and south-central South America, where it is generally among the most ubiquitous birds in bodies of standing freshwater. In the U.S., it is especially abundant from coastal Texas to South Carolina, including all of Florida. (For the Hawaiian and Andean forms, see “Hawaiian Gallinule” and “Altiplano Gallinule”.)

Common Gallinule

Gallinula galeata

The Americas from Canada to Argentina, in ponds, lakes, and wetlands with a mix of open water and emergent vegetation.

Approximate distribution of the Common Gallinule (including “Altiplano Gallinule”). © Xeno-Canto 2021

Comprises three distinct forms: the widespread “American Gallinule” (galeata plus cachinnans, cerceris, barbadensis, and pauxilla) and two localized forms, each covered separately: the “Hawaiian Gallinule” (sandvicensis), of the southeastern Hawaiian Islands; and the “Altiplano Gallinule” (garmani), of the central Andean Plateau from north-central Peru to northern Chile and northwestern Argentina.

In North America, breeds locally in interior wetlands of the West north to northern California, southern Nevada, and New Mexico, and in bottomlands of the East from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley south to the Gulf of Mexico, and along the Atlantic coastal plain from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to Florida. Winters mainly along the southern tier of states from California to Florida.

In spring, overshooting migrants regularly wander north to Oregon, Utah, Colorado, and the Maritime provinces; more exceptionally to British Columbia, Montana, Manitoba, and Newfoundland.

In Middle America: breeds locally in appropriate habitat throughout Mexico and Central America. In winter it becomes more numerous and widespread.

In the West Indies, resident essentially throughout: from Cuba and the Bahamas to the ABC Islands and Trinidad. Also resident on Bermuda and the Galápagos Islands.

In South America, resident in the Pacific lowlands from Colombia to southern Peru, and locally south to central Chile; in the intermontane valleys of Colombia; throughout the Caribbean lowlands, locally south into the Llanos of Colombia and Venezuela and east through the Guianas; sparse and localized in Amazonia; then widespread south and east of Amazonia to central Argentina (to Mendoza, northern La Pampa, and southern Buenos Aires Province).

Wanderers regularly disperse south to Valdivia, Chile; and exceptionally to Chiloé Island and Tierra del Fuego.

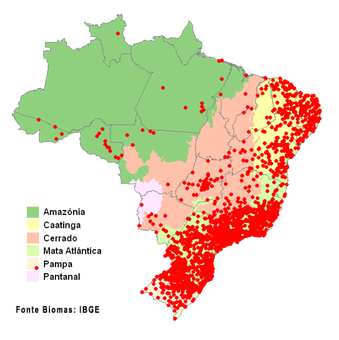

Brazilian records from © Wikiaves

Identification

The familiar gallinule (or moorhen) of the Americas: a large, plump, aquatic rail that often swims like a duck.

Predominantly black or blackish overall with a bold red bill, white undertail coverts, and white streaks on the flanks.

The bill and frontal shield are strikingly vivid red with a yellow tip.

The back and wings are usually brownish, but the extent and tone vary from warm-brown to black.

The legs are mostly greenish, but partly red above the “knees” and sometimes partly red below as well.

Common Gallinule. (Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, Texas; July 21, 2017.) © Dwayne Litteer

Common Gallinule. (Fluvanna Ruritan Lake, Virginia; June 1, 2020.) © Tucker Beamer

Common Gallinule. (Add Lake, Los Angeles, California; November 6, 2020.) © Steven Kurniawidjaja

Common Gallinule. (South Padre Island, Texas; February 23, 2020.) © Chris Charlesworth

Common Gallinule. (Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive, Apopka, Florida; January 11, 2020.) © Reanna Thomas

Common Gallinule. (Emily Renzel Wetlands, Palo Alto, California; June 19, 2019.) © Jim Dehnert

Common Gallinule. (Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District, San Rafael, California; May 30, 2016.) © Matt Davis

Common Gallinule. (Bávaro, Dominican Republic; January 18, 2018.) © Aves del NEA

Common Gallinule. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; July 16, 2019.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule, showing extensive red on the legs. (New Providence, Bahamas; February 24, 2017.) © Corey Finger

Common Gallinule, showing broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive, Apopka, Florida; June 25, 2016.) © S.K. Jones

Common Gallinule, showing its broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (South Padre Island, Texas; January 21, 2018.) © Andrew Simon

Common Gallinule, close-up view of broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District, Marin County, California; March 31, 2018.) © Matt Davis

Common Gallinule, close-up view of frontal shield, showing a more rounded top edge than most. (Lagunas de Doña Ana Park, Cartago, Costa Rica; December 30, 2017.) © Jose Pablo Castillo

Common Gallinule. (Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, Florida; December 12, 2016.) © John Whigham

Common Gallinule. (South Padre Island, Texas; October 1, 2019.) © Ad Konings

Common Gallinule, showing mostly blackish upperparts. (Leonabelle Turnbull Birding Center, Port Aransas, Texas; January 27, 2016.) © Scott Martin

Common Gallinule, showing mostly blackish upperparts. (South Hero Marsh Trail, Grand Isle, Vermont; May 17, 2020.) © Henry Trombley

Common Gallinule, with rusty-brown upperparts. (South Padre Island, Texas; June 3, 2017.) © Marky Mutchler

Common Gallinule, close-up view of broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (South Padre Island, Texas; June 3, 2017.) © Marky Mutchler

Common Gallinule, showing a maximally broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (Gamboa Rainforest Resort, Panama; February 18, 2018.) © Marie O’Neill

Common Gallinule. (Graeme Hall Nature Sanctuary, Barbados; February 24, 2014.) © Stephen Gast

Common Gallinule. (South Padre Island, Texas; October 1, 2019.) © Don Danko

Common Gallinule. (Papago Park, Phoenix, Arizona; January 27, 2018.) © Sean Fitzgerald

Common Gallinule. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; March 17, 2019.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; October 14, 2020.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule. (Finca Maragrícola, Nariño, Colombia; January 7, 2020.) © Sean Williams

Common Gallinule. (Finca Maragrícola, Nariño, Colombia; January 7, 2020.) © Sean Williams

Geographical Variation. Both localized forms—“Hawaiian Gallinule” and “Altiplano Gallinule”—typically have blacker upperparts than the widespread “American Gallinule”.

The localized forms also differ to some extent in size and structure. Most notably, “Altiplano” is heavier and longer-winged than the others.

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing mostly blackish upperparts as is typical of this form. (Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, Kauai, Hawaii; June 9, 2018.) © Sharif Uddin

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing extensive red on the tarsus—which is more common in this form than in others. (Koloa, Kauai, Hawaii; March 12, 2020.) © Bruce Davis

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing an exceptionally large frontal shield. (Ohiki Road, Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, Kauai, Hawaii; December 28, 2015.) © Carl Giometti

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing mostly blackish upperparts as is typical of this form. (Hokuala Golf Course, Lihue, Kauai, Hawaii; February 9, 2020.) © Jan Liang

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing mostly blackish upperparts and extensive red on the tarsus—both typical of this form. (Hokuala Golf Course, Lihue, Kauai, Hawaii; October 3, 2015.) © Noam Markus

“Hawaiian Gallinule,” G. g. sandvicensis, showing an exceedingly broad, flat-topped frontal shield, as well as mostly blackish upperparts and extensive red on the tarsus—all typical of this form. (Pouhala Marsh, Oahu, Hawaii; July 24, 2012.) © Erik Atwell

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Parque del Bicentenario, Salta, Argentina; December 12, 2017.) © Michael Weymann

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing large and almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Laguna Huasao, Cuzco, Peru; September 30, 2016.) © Robin Oxley

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing large and almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Humedal de Huayllarcocha, Cuzco, Peru; July 14, 2018.) © David Coates

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Humedal de Huayllarcocha, Cuzco, Peru; July 14, 2018.) © David Coates

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Purmamarca, Jujuy, Argentina; September 15, 2002.) © Tini & Jacob Wijpkema

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, appearing almost all-black, as is typical of this form. (Islas Uros, Lake Titicaca, Puno, Peru; August 22, 2012.) © Tim Avery

“Altiplano Gallinule,” G. g. garmani, showing brownish upperparts—not typical but not uncommon in this form. (Laguna Pomacochas, Amazonas, Peru; May 29, 2019.) © Michael Clay

“American Gallinule,” G. g. cachinnans, dark adult with chick. (Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, Florida; August 5, 2015.) © Hal and Kirsten Snyder

“American Gallinule,” G. g. galeata, such as this one, can also appear mostly black. (Costanera Sur Ecological Reserve, Buenos Aires, Argentina; January 20, 2018.) © Ricardo A. Palonsky

Immature Plumages. Immatures resemble adults but have more muted coloration: gray overall with brown back and wings and a dull brownish, pale-tipped bill.

Subadults go through a stage when they have mostly adult plumage but the bill is dull and shieldless. The bill then grows the frontal shield and flushes with the bright red and yellow of adulthood.

Common Gallinule, immature. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; November 3, 2019.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule, immature. (Buckeye Lake, Licking County, Ohio; September 4, 2018.) © Brad Imhoff

Common Gallinule, immature. (Sasaki Seasonal Pond, Aruba; May 26, 2017.) © Michael Tromp

Common Gallinule, immature. (Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, California; November 1, 2020.) © Matt Davis

Common Gallinule, subadult, showing mostly adult plumage with dull brownish bill. (Riparian Preserve at Gilbert Water Ranch, Gilbert, Arizona; January 1, 2020.) © Gordon Karre

Common Gallinule, subadult, showing mostly adult plumage with dull brownish bill. (Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, Sacramento, California; January 6, 2017.) © Matt Davis

Common Gallinule, immature. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; July 29, 2019.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule, immature. (Bubali Bird Sanctuary, Aruba; March 29, 2018.) © Michiel Oversteegen

Common Gallinule, adult and immature. (Lake Lucerne, Orlando, Florida; August 30, 2017.) © Bobbie Elbert

Common Gallinule, subadult. (Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York; November 14, 2017.) © Sean Sime

Common Gallinule, subadult, showing mostly adult plumage with dull brownish bill. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; October 14, 2020.) © Harlan Stewart

Common Gallinule, subadult, showing mostly adult plumage with dull brownish bill. (Tyrrell Park, Beaumont, Texas; October 14, 2020.) © Harlan Stewart

Voice. Vocal repertoire includes various clucks, grunts, chirps, bleats, and squeaks. Its most distinctive call is an exuberant cackle: Typical contact call is a soft but sharp squeak or grunt: Also trumpets weakly:

Cf. Eurasian Moorhen. The Eurasian Moorhen and its New World counterpart, the Common Gallinule, were traditionally classified as separate species, then for a few decades were widely regarded as conspecific, then in 2011 again formally reclassified as separate. They are extremely similar in appearance, and the visible differences between them are subtle characteristics that vary within each species and overlap between them.

They do not normally occur together, so geographical probability is usually sufficient for identification. However, both are capable of long-distance vagrancy, and it seems likely that they occur in one other’s ranges much more often than the few records would suggest—as their similarities are so strong that most vagrants would go undetected even if studied carefully.

The main differences are: (1) general proportions; (2) size and shape of the frontal shield; (3) vocalizations; and (4) eye color.

Eurasian Moorhen. (Campania, Italy.) © Ciro de Simone

Common Gallinule. (Leonabelle Turnbull Birding Center, Port Aransas, Texas; January 27, 2016.) © Scott Martin

General Proportions: The Common Gallinule averages slightly larger overall than Eurasian Moorhen, but its proportions are lankier and give it the appearance of being significantly larger. Its legs and neck are proportionately longer and its head has a more angular shape—whereas the moorhen appears compact, plump, rounded, and dove-headed. These distinctions are not absolute and are often difficult to evaluate in isolation.

Eurasian Moorhen. (Brüglingen Botanischen Gartens, Basel, Switzerland; October 16, 2019.) © Maryse Neukomm

Common Gallinule. (Peaceful Waters Sanctuary, Palm Beach County, Florida; August 3, 2019.) © David Hall

Common Gallinule, close-up view of broad, flat-topped frontal shield. (Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District, Marin County, California; March 31, 2018.) © Matt Davis

Eurasian Moorhen, close-up view of small, narrow frontal shield—but with a flatter-than-average top edge. (Phoenixsee, Dortmund, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany; February 1, 2019.) © Guido Bennen

Frontal Shield: The most objective and generally consistent visible distinction appears to be the shape of the red frontal shield: the gallinule’s averages larger, broader, and more flat-topped than the moorhen’s—perhaps the best indication is distance to the eye, which is greater on the moorhen. On the Eurasian Moorhen, the sides of the shield are mostly parallel until it curves inward near the upper edge, whereas on the Common Gallinule, its sides tend to broaden and reach distinct corners at the upper edge. However, when comparing frontal shields it quickly becomes apparent that their sizes and shapes vary widely within each species. In particular, the gallinule’s shield starts small, then grows, so an individual with a small shield could belong to either species.

Vocalizations: The moorhen and gallinule are vocally distinct. Both have large repertoires, however, and some vocalizations might be difficult to identify in the field. Both sometimes give sharp squeaks, grunts, and chirps, with no particular pattern—in these cases the gallinule’s notes tend to be higher-pitched. The moorhen characteristically gives percussive polysyllabic or rolling calls (e.g., ti-ti-ti or p-r-r-r-t), whereas she gallinule’s characteristic calls are exuberant cackles and weak trumpets or squeals.

Eurasian Moorhen with a larger-than-average frontal shield—appearing more typical of Common Gallinule. (Slimbridge Wetland Centre, Gloucestershire, England; March 11, 2012.) © Simon Bradfield

Eye Color: Eurasian Moorhen typically shows distinctly reddish irises, whereas Common Gallinule’s eyes typically appear dark-brown. However, eye color varies somewhat, especially in the moorhen, and is subject to strong differences due to lighting.

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of seven recognized subspecies which represent three potentially distinct forms: the widespread “American Gallinule” (galeata, cachinnans, cerceris, barbadensis, and pauxilla) and the regional “Hawaiian Gallinule” (sandvicensis) and “Altiplano Gallinule” (garmani).

For several decades, regarded as conspecific with its Old World counterpart, the Eurasian Moorhen (chloropus), known collectively as the Common Moorhen (G. chloropus) but classified as separate species since 2011.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2016. Gallinula galeata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T62120280A95189182. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T62120280A95189182.en. (Accessed January 2, 2021.)

de la Peña, M.R., and M. Rumboll. 1998. Birds of Southern South America and Antarctica. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed January 3, 2021.)

Fagan, J., and O. Komar. 2016. Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garrigues, R., and R. Dean. 2014. The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (Second Edition). Cornell University Press.

Haynes-Sutton, A., A. Downer, R. Sutton, and Y.-J. Rey-Millet. 1986. A Photographic Guide to the Birds of Jamaica. Princeton University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Jaramillo, A. 2003. Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pratt, H.D. 1993. Enjoying Birds in Hawaii: A Birdfinding Guide to the Fiftieth State (Second Edition). Mutual Publishing, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Raine, H., and A.F. Raine. 2020. ABA Field Guide to the Birds of Hawai’i. Scott & Nix, Inc., New York.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Ripley, S.D. 1977. Rails of the World: A Monograph of the Family Rallidae. David R. Godine, Publisher, Boston.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Taylor, B., and B. van Perlo. 1998. Rails: A Guide to the Rails, Crakes, Gallinules, and Coots of the World. Yale University Press.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2021. Frango-d’água-comum. http://www.wikiaves.com/wiki/frango-d_agua-comum, (Accessed January 3, 2021.)

Xeno-Canto. 2021. Common Gallinule – Gallinula galeata. https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Gallinula-galeata. (Accessed January 3, 2021.)