Birdfinding.info ⇒ The eastern Pacific form of Band-rumped Storm-Petrel is fairly common in the Galápagos archipelago year-round, often seen at sea on transits among the islands. Rarely seen elsewhere, though sightings indicate that it is likely regular in the offshore waters of Costa Rica and Panama.

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”

Hydrobates castro bangsi

Breeds in the Galápagos; disperses across the eastern tropical Pacific.

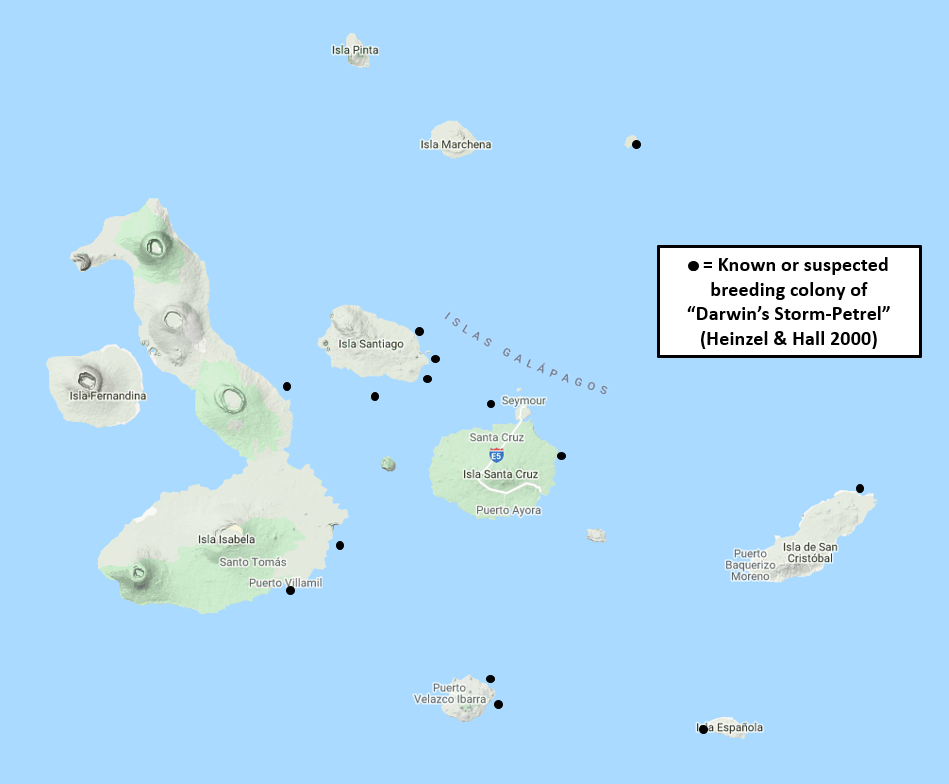

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel” breeding sites, from Heinzel & Hall (2000).

Breeds in several colonies scattered essentially throughout the Galápagos archipelago, in two seasonally segregated populations. One population breeds from May to October and the other breeds from December to May. (Note that Howell & Zufelt regard the former as “Darwin’s” and the latter as a distinct form or species, “Spear’s Storm-Petrel”. This classification has not been widely adopted, pending further elucidation of possible differences between the populations.)

Most of the reported colonies are on islets or coastal cliffs of the major islands: Isabela (on three eastern islets); Santiago (on Rábida, Chino, and two more eastern islets); Santa Cruz (on Plaza Norte and Daphne Major); Genovesa (near Great Darwin Bay); Floreana (on two eastern islets); San Cristóbal (on one northeastern islet); and Española (Punta Suarez).

When not breeding both populations either remain within Galápagos waters or disperse elsewhere in the eastern Pacific. The extent of dispersal is not fully understood, but it has been found regularly north to Costa Rican and Panamanian waters, south to the latitudes of southern Peru and west across the Pacific past the longitude of Easter Island.

May also wander north and west to distant offshore waters southwest of Baja California and east-southeast of Hawaii—a vast area of open ocean where long-haul oceanographic cruises have produced a few reports of band-rumped-type storm-petrels that could be either “Darwin’s” or “Hawaiian”.

Identification

As a form or potentially cryptic species within the Band-rumped Storm-Petrel complex, “Darwin’s” is visually indistinguishable from other Pacific band-rumped-type storm-petrels.

Identification is based solely on geographical probability—i.e., any band-rumped-type storm-petrel observed in the tropical eastern Pacific is generally presumed to be “Darwin’s”, although this presumption becomes weaker westward, gradually shifting to “Hawaiian”.

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi, showing typical pattern and gliding flight posture. (Offshore south of Isla San Cristóbal, Galápagos, Ecuador; November 25, 2019.) © David M. Bell

Like other band-rumped-type storm-petrels, “Darwin’s” is dark-brown overall, with an even white band across the rump that usually extends partway down the sides of the rump to the undertail. Its tail usually appears either square-tipped or shallowly notched.

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi, lateral profile view, showing white extending down the side of the rump. (Offshore south of Isla San Cristóbal, Galápagos, Ecuador; November 25, 2019.) © David M. Bell

As with most dark storm-petrels, all band-rumped-types typically show a paler brown or whitish diagonal stripe on the wing coverts, but the boldness varies depending on molt-stage and lighting. So the apparent color and boldness of the wingbar can provide clues to the age and molt-stage of closely observed individuals.

Juveniles and freshly molted adults have the most pronounced wingbars. On juveniles the bar appears silvery. On fresh adults, the bar is blond. With feather-wear, the bar diminishes and may disappear entirely by the time the next molt begins.

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi. (Offshore south of Isla San Cristóbal, Galápagos, Ecuador; November 25, 2019.) © David M. Bell

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi, in hand following a nonlethal collision with a vessel. (Offshore west of Isla San Cristobal, Galápagos, Ecuador; July 17, 2010.) © Michael O’Brien

Voice. There appear to be no publicly available recordings. In general, band-rumped-type storm-petrels give two main call-types at breeding colonies, chattering and purring, but they differ in their patterns.

Studies of the vocalizations of North Atlantic band-rumpeds have been instrumental to understanding the relationships among similar-looking forms. Such studies in the Pacific will likely be needed to understand the taxonomic status of each breeding population.

Notes

Monotypic form, one of seven or more potentially distinct forms of Band-rumped Storm-Petrel (castro), which is in the midst of taxonomic revisions. Eventually, it seems likely that the Pacific forms will be classified as one or more species separate from the Atlantic forms.

Howell and Zufelt (2019) provisionally classify of each Pacific breeding population as a separate species: “Japanese” (kamagai), “Hawaiian” (cryptoleucurus), “Darwin’s” (bangsi), and “Spear’s” (sp. nova). The latter two forms refer to seasonally distinct breeding populations of the Galápagos, which are not known to be distinguishable except based on their egg-laying calendars.

A study published in 2019 (Taylor et al.) concluded that all of the Pacific forms were closely related to one another, but also to one of the South Atlantic forms (helena). The close affiliation of the Pacific populations is not surprising, but their apparent affiliation with one Atlantic population presents an unanticipated complication.

Additional Photos of “Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi, showing long, thin wings. (Offshore northwest of Isla Isabela, Galápagos, Ecuador; May 29, 2016.) © Charles Davies

“Darwin’s Storm-Petrel”, H. c. bangsi (as identified by the photographer), on nest. (Great Darwin Bay, Isla Genovesa, Galápagos, Ecuador; November 30, 2013.) © John Hannan

References

BirdLife International. 2018. Hydrobates castro. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T132341128A132433305. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T132341128A132433305.en. (Accessed December 20, 2021.)

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed December 20, 2021.)

Harris, M.P. 1973. The Galápagos Avifauna. The Condor 75:265-278.

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Heinzel, H., and B. Hall. 2000. Galápagos Diary: A Complete Guide to the Archipelago’s Birdlife. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Howell, S.N.G. 2012. Petrels, Albatrosses & Storm-Petrels of North America. Princeton University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press.

Onley, D., and P. Scofield. 2007. Albatrosses, Petrels & Shearwaters of the World. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Taylor, R.S., M. Bolton, A. Beard, T. Birt, P. Deane-Coe, A.F. Raine, J. González-Solís, S.C. Lougheed, and V.L. Friesen. 2019. Cryptic species and independent origins of allochronic populations within a seabird species complex (Hydrobates spp.). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 139:106552.