The Avitourist’s Guide to the Big Island

Easily the weirdest of the Big Island’s endemic birds is the Akiapola’au. © Eric VanderWerf

Comprising nearly two-thirds of Hawaiian soil, the Big Island accounts for its largest complement of bird diversity. With eight remaining species found nowhere else, the Big Island counts the most endemics among the Hawaiian Islands. Those that have survived into the 2020s are the Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, Hawaiian Crow, Oma’o, Palila, Akiapola’au, Hawaii Creeper, and Hawaii Akepa—but as of 2021 the crow exists only in captivity, leaving seven single-island endemics for visitors to observe in nature.

Highlands

The Big Island’s endemics are concentrated in a few remaining montane forests at middle elevations of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Its four unique honeycreepers are confined to such forests, while its endemic hawk, monarch, and thrush all occur in these forests and also across a wider set of habitats.

Endemic Birds of the Big Island

The Big Island endemic Hawaiian Hawk is plump and broad-winged compared to its closest continental relatives. © Alan Schmierer

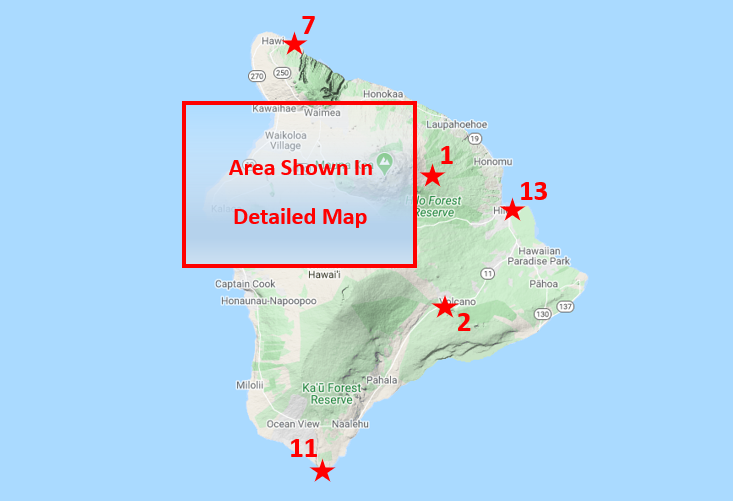

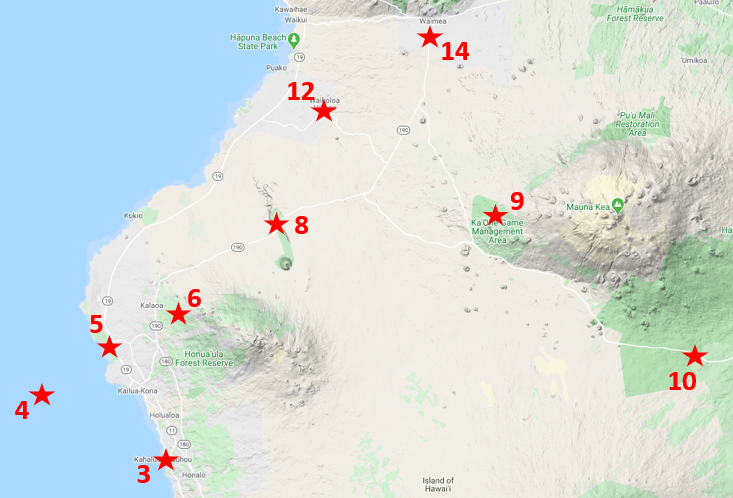

To maximize the odds of seeing all of the findable endemics, prospective travelers should research the conditions for visiting Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge (Site #1 on the map below), a remote tract on the northeastern slopes of Mauna Kea, where access has been restricted due in part to invasive diseases killing the trees. That is the only accessible area where Hawaii Creeper and Hawaii Akepa are readily found, and it is the most reliable site for Akiapola’au. All three of these rarities can also be found, but less reliably, where public access is not restricted, in the kipukas along Saddle Road (Site #10)—the Pu’u O’o Trail is best for Akiapola’au, while the “3-Mile Kipuka” is best for the other two.

The Palila is limited to dry montane forest with abundant seed pods, most reliably at Pu’u La’au (Site #9) on the southwestern slopes of Mauna Kea, where access is not restricted but may require special effort. It can sometimes also be found, but much less reliably, where the paved road ends a few miles east at the Mauna Kea Visitor Center, also accessed from Saddle Road.

The Big Island endemic Hawaiian Crow. © San Diego Zoo Global

The most critically endangered Big Island endemic, the Hawaiian Crow, disappeared as a wild species in 2002, but has been preserved through a captive breeding program. Reintroduction efforts began tentatively in 2016 at Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve on the eastern slopes of Mauna Loa, a few miles north of the headquarters of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (Site #2), but hope for free-flying crows in the park dimmed when an unsustainably high mortality rate forced abandonment of this phase of reintroduction.

The three widespread Big Island endemics can be found at all of the sites mentioned above: the Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, and Oma’o. These three can also be found, but much less reliably, on the forested hillsides above Kailua-Kona at Kaloko Mauka (Site #6), on the western slope of the dormant volcano Hualalai.

Other Hawaiian Endemics Found on the Big Island

In addition to the aforementioned Big Island endemics, these montane forest sites are home to three more widespread honeycreepers that are endemic to Hawaii but occur on multiple islands: Apapane (on all the major islands), I’iwi (also on Maui and Kauai), and Common Amakihi (also on Maui and Molokai). Most of these sites also have potential for Hawaiian Goose, which occurs in meadows at all elevations throughout the Big Island (and also on Kauai, Maui, and Molokai).

Wetlands

The Big Island has fewer wetlands than Kauai and Oahu, but some are highly productive. Between Kailua-Kona and its airport, Kealakehe Wastewater Treatment Plant and Aimakapa Pond (in the heart of the Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park, Site #5) support breeding populations of Hawaiian Coot and “Hawaiian Stilt” (a distinct form of Black-necked Stilt). On the other side of the island, in Hilo, the coot can be found at Wailoa River State Park (Site #13), along with Hawaiian Goose.

The many golf courses along the Kona coast have ponds that attract waterfowl and shorebirds, including Hawaiian Goose, Pacific Golden-Plover and Bristle-thighed Curlew. The goose can be found on most of these golf courses, but is especially reliable at the Makani Golf Club (Pu’u Anahulu, Site #8) and Waikoloa (Site #12). The curlew has been a regular visitor to Mauna Lani Golf Course west of Waikoloa.

The most challenging endemic Hawaiian waterbird that occurs on the Big Island is the Hawaiian Duck, which is localized mainly along rivers and streams of the Kohala Range. It is found most often in bottoms of the Pololu (Niuli’i, Site #7) and Waipio Valleys, and less often on ponds and streams in the vicinity of Waimea (Site #14).

Seabirds

The Big Island counts two of the most productive seawatch points in Hawaii, Keahole Point and Keokea Beach Park, where a wide array of pelagic species can be seen from shore—especially when aided by high-powered optics.

The latter site, at Niuli’i (Site #7), near the northern tip of the island, has proven to be consistent, in season, for five Pterodroma petrels (Black-winged, Cook’s, Mottled, Juan Fernández, and Hawaiian) and five shearwaters (Wedge-tailed, Buller’s, Sooty, Short-tailed, and Newell’s), as well as Yellow-billed and Red-tailed Tropicbirds, Great Frigatebird, Red-footed and Brown Boobies, and “Hawaiian Noddy” (a distinct form of Black Noddy that seems likely to be recognized as a separate species).

The former site, conveniently located beside Kona International Airport (and the Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park, Site #5), has less diversity but regularly produces “Hawaiian Storm-Petrel” (a potentially distinct form of Band-rumped Storm-Petrel), Bulwer’s Petrel, and Masked Booby, among others.

For those who can coordinate their visits accordingly, the Big Island birdwatching community has often (a few times per year in the late 2010s and early ‘20s) organized pelagic boat trips to the waters offshore from Kailua-Kona (Site #4). These excursions have produced sightings of most of the species listed above, and others, such as Stejneger’s, Kermadec, Murphy’s and White-necked Petrels, and Christmas Shearwater.

A major tourist destination that offers unique opportunities to see pelagic birds is Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (Site #2), where Yellow-billed Tropicbirds nest on the walls of the caldera and “Hawaiian Noddies” routinely fly within easy view of the Chain of Craters Road. Finally, the southernmost promontory of the fifty states, South Point (Site # 11), is not as prolific a seawatch as its prime location might suggest, but it is reliable for a handful of oceanic birds, and during 2021 produced the first U.S. record of Inca Tern, proving its potential.

Exotics

The Big Island has a disproportionate share of share of exotic (i.e., non-native) species, including four (Kalij Pheasant, Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse, Lavender Waxbill, and Yellow-billed Cardinal) that are not established anywhere else in the U.S., and two more with small populations that would be unique if they became well established: Tanimbar Corella and Burrowing Parakeet.

The Big Island’s introduced population of Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse is the sole representative of its family in the U.S. © Ramesh Desai

There are, in addition, many introduced species that can be found more readily on the Big Island than other islands: California Quail, Wild Turkey, Chukar, Erckel’s Francolin, Japanese Quail, Indian Peafowl, Red-masked Parakeet, Rosy-faced Lovebird, Eurasian Skylark, Red-billed Leiothrix, Red Avadavat, Yellow-fronted Canary, and Saffron Finch.

One area in particular, the ranchland around Pu’u Anahulu (Site #8) was the gateway though which many species from around the globe were released into Hawaii. The largest portions of these experimental introduction efforts were gamebirds and finches. Most did not become established, though a few—such as Red-billed Francolin, Red-cheeked Cordonbleu, and Black-rumped Waxbill—seemed close to succeeding before they apparently succumbed.

The Big Island – Orientation Map

Planning a Visit

The Big Island is large and challenging enough that prospective visitors should consider their options and prioritize before committing to plans or accommodations. The endemic landbirds are concentrated in montane forests of Mauna Kea, best accessed from Saddle Road, which spans from Hilo to Waimea. Most of the island’s grassland can be found in adjacent areas. Seabirds are best sought around Kailua-Kona, ideally through an organized boat excursion to offshore waters. The most unusual exotics are also concentrated along the Kona Coast, as are most of the productive ponds. The northern tip is somewhat distant, but it offers a few unusual possibilities and may reward exploration. The south and east are dominated by volcanoes and the national park, essential sights for the Hawaiian nature tourist, but less so for Hawaiian birds.

Mauna Kea

All of the Big Island’s seven findable endemics can be found on the slopes of Mauna Kea. The key sites vary in their accessibility and the amount of preparation required to visit them. Along the well-paved cross-island highway, Saddle Road, it is possible to reach sites that offer at least a reasonable prospect of finding each species. For higher odds of finding the rarer species, it is necessary to venture farther from the beaten path: to Pu’u La’au for the Palila and Hakalau Forest for the Akiapola’au, Hawaii Creeper, and Hawaii Akepa. Pu’u La’au requires either a high-clearance vehicle or a fairly long hike. Hakalau Forest requires advance planning and the additional expense of hiring one of the few authorized guides.

Saddle Road (Site #10): Kipukas are patches of forest that are spared from destruction in a volcanic eruption and afterward remain as intact habitat islands surrounded by barren expanses of lava. The most accessible examples are along Saddle Road on the southeastern flank of Mauna Kea, part of a landscape that supports the highest diversity of surviving endemic Hawaiian birds, including small populations of four endangered honeycreepers (Palila, Akiapola’au, Hawaii Creeper, and Hawaii Akepa), as well as Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, Oma’o, and three common honeycreepers (Apapane, I’iwi, and Common Amakihi).

The Big Island endemic Palila. © Michael Walther

Pu’u La’au (Site #9): If you want to see a Palila, there is no better place than the Palila Forest Discovery Trail at Pu’u La’au. The remnants of native dry forest high on the western slope of Mauna Kea are the last stronghold of this unique honeycreeper, also home to a distinctive population of Hawaii Elepaio, and an abundance of Common Amakihi. Among the many introduced species present, Erckel’s Francolin is notably common and Japanese Quail is uncommon but significant because of its global decline.

Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge (Site #1): On the wet, windward, northeastern flank of Mauna Kea is a remote forested refuge that protects the healthiest remaining populations of three endangered honeycreepers, the Hawaii Akepa, Hawaii Creeper, and the rare and peculiar Akiapola’au. Hakalau Forest is a challenging destination due to both remoteness and protective restrictions on visitor access, requiring the services of a permitted guide. Besides its signature specialties, the refuge is home to several other Hawaiian endemics, including Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, Oma’o, Apapane, I’iwi, and Common Amakihi.

Kona

Most visitors to the Big Island arrive at Kona International Airport, and a large portion make their temporary home somewhere along the Kona Coast. In addition to being the island’s commercial and leisure capital, it also provides the best access to marine activities, including deep-sea fishing and pelagic birdwatching. The coastline includes many sheltered bays and prehistoric fishponds that attract various waterbirds, and the many manicured, well-irrigated resorts and golf courses support a diverse assortment of introduced birds.

Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park (Site #5): The coastal zone between Kailua-Kona and its airport contains the Big Island’s two most productive waterbird sites, Aimakapa Pond and the Kealakehe Wastewater Treatment Plant, and one of its best seawatching sites, Keahole Point. Hawaiian Coot and “Hawaiian Stilt” breed locally, and migratory waterfowl and shorebirds are seasonally numerous and diverse, often including vagrants from both sides of the Pacific. Exotic landbirds of interest include Black and Gray Francolins and Red-masked Parakeet. Seabirds seen regularly from shore include “Hawaiian Storm-Petrel”, Bulwer’s Petrel, and Masked Booby, in addition to commoner species.

“Hawaiian Storm-Petrel” can sometimes be seen from shore at Keahole Point. © Annie B. Douglas / Cascadia Research Collective

Kahaluu-Keauhou (Site #3): The coastline south of Kailua-Kona is arid and naturally barren, but coastal development and irrigation provide habitat for the only introduced populations of Lavender Waxbill and (more tenuously) Burrowing Parakeet, as well as the also-rare but more widely introduced Red-masked Parakeet and Java Sparrow. A few native species persist along the Kona coast, including Yellow-billed Tropicbird, Wandering Tattler, and Hawaiian Hawk.

Kaloko Mauka (Site #6): Most visitors to the dry Kona Coast are unaware that just a few miles away is a lush cloud forest. Parts of that forest are accessible along Kaloko Drive, which winds for seven miles up the dormant Hualalai volcano through the Kaloko Mauka (i.e., Kaloko Heights) subdivision, which was one of the last accessible sites for Hawaiian Crow. The endangered crows have vanished, but the area remains scenic and supports a mixture of introduced and native species, including Erckel’s Francolin, Kalij Pheasant, Hawaiian Hawk, Red-masked Parakeet, Tanimbar Corella, Hawaii Elepaio, Red-billed Leiothrix, Apapane, I’iwi, and Common Amakihi.

Pu’u Anahulu (Site #8): In the early and mid-1900s the ranchland around Pu’u Anahulu was Ground Zero for a steady stream of intentional introductions of non-native birds, especially gamebirds and finches, including a few that still persist. Most of the species introduced did not become established, and some flourished briefly then disappeared. Into the early 2000s, Pu’u Anahulu had eight waxbill species: Lavender, Common, and Black-rumped, Red-cheeked Cordonbleu, Red Avadavat, African Silverbill, Scaly-breasted Munia, and Java Sparrow. At least six of them remain, along with several other exotics, and the area still supports a few endemics, including Hawaiian Goose, Hawaiian Coot, “Hawaiian Stilt”, Hawaiian Hawk, and Common Amakihi.

Kailua-Kona, Offshore (Site #4): Hawaiian pelagic birdwatching remains a largely unexplored frontier, yet the productive waters just offshore from Kailua-Kona are within easy reach of any traveler, even those on a tight budget. The distance from the shore to deep ocean is minimal, and over twenty species of tubenoses are known to occur regularly: including at least five Pterodroma petrels and six shearwaters. This is among the most accessible areas that are consistent for several species, including “Hawaiian Storm-Petrel” and Black-winged, White-necked, Juan Fernández, and Bulwer’s Petrels. Other seabirds seen regularly include two species of tropicbird, three boobies, and South Polar Skua.

Black-winged Petrel can often be found offshore from Kailua-Kona. © Hiroyuki & Shoko Tanoi

Juan Fernández Petrel can often be found offshore from Kailua-Kona. © Hiroyuki & Shoko Tanoi

North

The northernmost portion of the Big Island is the Kohala Peninsula, a collection of rural communities which most tourists do not even consider exploring. Its windswept coastline has gained some attention for productive seawatching, mostly at Keokea Beach Park, and the area apparently supports small breeding populations of Red-tailed Tropicbird and Hawaiian Duck. The two routes into Kohala pass through Waikoloa and Waimea, each of which has a few unusual species to pursue.

Niuli’i (Site #7): The road through Kohala ends at a village called Niuli’i, where a remarkably diverse set of seabirds often approach close enough to be seen from shore through strong optics. Five Pterodroma petrels appear to be regular—Black-winged, Cook’s, Mottled, Juan Fernández, and Hawaiian—and five shearwater species have been reported regularly: Wedge-tailed, Buller’s, Sooty, Short-tailed, and Newell’s. Both Yellow-billed and Red-tailed Tropicbirds apparently nest high on the cliffs, with “Hawaiian Noddies” at the bottom, and Hawaiian Ducks and Hawaiian Hawks in the adjacent valley.

Waikoloa (Site #12): Waikoloa Village is an artificial oasis in the Big Island’s northern desert. Among birdwatchers it has become known as the most convenient place in the U.S. to see Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse, and a reliable spot for Hawaiian Goose, Gray Francolin, and Rosy-faced Lovebird. The nearby South Kohala coastline, from Waikoloa Beach to Holoholokai Beach, is dominated by seaside resorts and golf courses that regularly host a flock of Bristle-thighed Curlew.

Waimea (Site #14): The Big Island’s agricultural center, Waimea, is notable for two scarce species—Hawaiian Duck and Japanese Quail—that have been found repeatedly, though not often, along its back roads. Tucked away in the northern interior of the island, not adjacent to any beach, mountain, or lava flow, Waimea receives little attention from most tourists. However, its low profile and central location make it a convenient base for exploring many of the Big Island’s highlights.

South and East

The southern and eastern portions of the Big Island include large expanses of wild and publicly inaccessible land, preserving populations of all the island’s remaining endemics except the Palila. The Hawaiian Crow reintroduction effort launched on one of these restricted tracts, the Pu’u Maka’ala Natural Area Reserve, in 2016, and was planned to proceed to two others, but its mortality rate was unsustainable, so that effort seems more likely to resume on Maui instead. The accessible areas of interest to visitors are concentrated in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, where the scenery and geology outperform the birdlife.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (Site #2): Hawaii Volcanoes National Park has a well-deserved reputation for scenic grandeur, fascinating geological formations, and the thrills of persistent volcanic activity. This awe-inspiring landscape is home to three Big Island endemics—Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, and Oma’o—and several multi-island endemics: Hawaiian Goose, “Hawaiian Noddy”, Apapane, I’iwi, Common Amakihi. Other notable avian highlights include locally numerous Kalij Pheasant and Yellow-billed Tropicbird nesting in the active part of the volcano.

The I’iwi has declined but can still be found at upper elevations of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. © Sharif Uddin

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park supports a high density of introduced Kalij Pheasants. © Michael Walther

South Point (Site #11): The southernmost piece of solid ground in the fifty states is a barren, windswept headland facing thousands of miles of open ocean. Travelers of the Mamalahoa Highway are drawn to it. Those who reach the point are likely to find Pacific Golden-Plover, Wedge-tailed Shearwater, “Hawaiian Noddy”, and Eurasian Skylark. A well-timed visit might yield Bristle-thighed Curlew or unusual seabirds. Inland along the highway nearby are a few trails where Erckel’s Francolin, Hawaiian Hawk, Hawaii Elepaio, Red-billed Leiothrix, Apapane, and Common Amakihi can be found.

Wailoa River State Park (Site #13): Hilo’s airport sits between two large ponds that attract a diverse mix of migratory waterfowl and other aquatic birds, especially in fall and winter. Waiakea Pond is an estuary at the center of the town’s main greenspace, Wailoa River State Park, and Lokowaka Pond is an attractive seaside lagoon on the eastern outskirts. Hawaiian Goose is common year-round at Waiakea Pond, a few Hawaiian Coots are typically present at both, and Hawaiian Hawk is sporadic throughout the area.