Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii

Haleakala National Park protects a large portion of Maui’s highlands, all formed by the volcano Haleakala (HAH-lay-ah-kuh-LAH). The main portion of the park that is publicly accessible is mostly open alpine terrain, with some patches of trees and brush. The most localized bird commonly found in the park is a Maui endemic, the Maui Alauahio. Another localized Maui endemic, the Akohekohe, is found very rarely. In the breeding season, the park hosts the world’s second largest colony of Hawaiian Petrel, which can be heard and sometimes seen at night along the main road. Several additional Hawaiian endemics can usually be found: Hawaiian Goose, “Hawaiian Short-eared Owl”, Apapane, I’iwi, and Common Amakihi.

Orientation

Directions

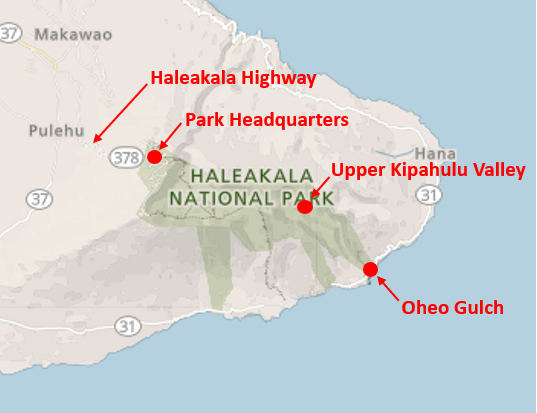

Haleakala National Park includes two accessible areas that are widely separated: (1) the main section, along road up to Haleakalā Crater and Peak; and (2) Oheo Gulch, along the southeastern coast of Maui, accessible via the Hana Highway. The latter is remote, has very few birds, and receives very few visitors.

To reach the main section of the park, take the Haleakala Highway: Route 37 past Pukalani, then turn left onto Route 377, then at Kula turn left again onto Route 378, which winds its way up to the park entrance.

Birdfinding

Most visitors to Haleakala National Park will approach the main sector via the Haleakala Highway and follow the main road into the park and up to the summit, stopping at a few key points along the way.

Haleakala Highway. The road winding uphill from Kula passes through a large park expanse of ranchland en route to the park. This drive often produces sightings of Common Pheasant, “Hawaiian Short-eared Owl”, and Eurasian Skylark.

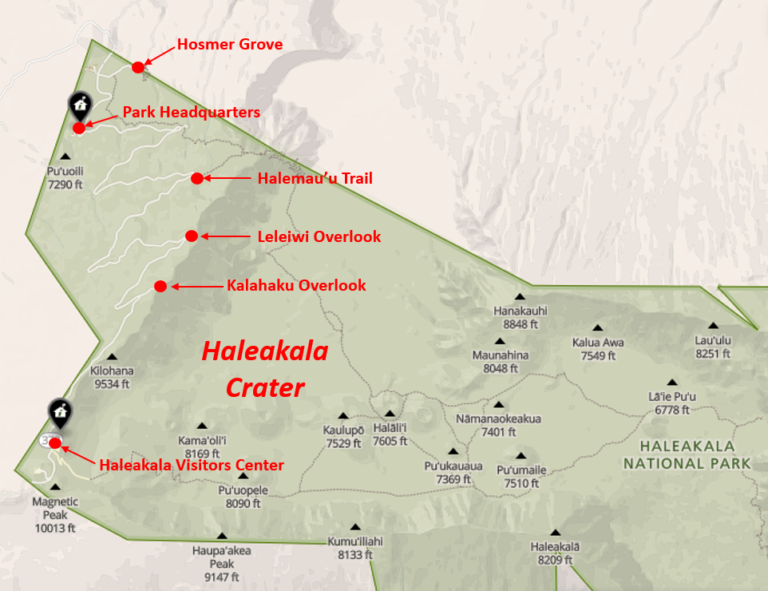

Hosmer Grove. Almost immediately after entering the park, a lefthand turn leads to the Hosmer Grove Campground, where there is a small nature trail that leads into a mostly non-native forest with a few native trees and flowers. With the exception of the adjacent Waikamoi Preserve, to which access is limited, the Hosmer Grove is Maui’s best option for searching for native landbirds. Species that are reliably present include four honeycreepers (Maui Alauahio, Apapane, I’iwi, and Common Amakihi), while a fifth, the rare endemic Akohekohe, has been seen here from time to time (especially in December), but is not to be expected. Hawaiian Goose can often be seen in open areas around the campground.

Maui Alauahio at the Hosmer Grove. © James Telford

Park Headquarters. Less than a mile upslope from the Hosmer Grove, the park headquarters area has been a consistent spot for Hawaiian Goose, usually “park tame” (wild but acclimated) individuals and Chukar.

Upper Elevations. The higher, rockier portion of the park are not embarrassed by an overabundance of birds, nor an excess of diversity. The most notable species to be found in the upper elevations are Hawaiian Goose, Chukar, and Hawaiian Petrel.

Chukar can be found anywhere along the road and at the trails and overlooks: Halemau’u Trail, Leleiwi Overlook, and Kalahaku Overlook.

Chukar is common at upper elevations of Haleakala National Park. © Hal and Kristen Snyder

Hawaiian Goose can usually be found at Haleakala National Park. © Graham Gerdeman

The second-largest colony of Hawaiian Petrels is along the rim of Haleakala Crater. © Jim Denny

Hawaiian Petrel can often be heard at night (and sometimes seen arriving around dusk) along the rim of Haleakala Crater from early March to mid-August. Several hundred pairs nest in burrows on the upper slopes and call persistently from soon after sunset to around midnight. The best place to hear (and sometimes see) them is along the main road about 500 m downhill from the Haleakala Visitors Center. The road passes close to the rim of the crater, and the petrels often fly low over this area.

Haleakala Crater. © Niagara66

Oheo Gulch. Far from the upper elevations of Haleakala, on the most remote stretch of the Hana Highway, at its southeasternmost point, the national park meets the coast at the bottom of the Kipahulu Valley. The Pipiwai Trail up to Waimoku Falls is good for Chinese Hwamei, and the ocean access at the Kipahulu Campground provides a good chance of seeing Yellow-billed Tropicbird, Great Frigatebird, “Hawaiian Noddy”, and occasionally other seabirds.

Upper Kipahulu Valley. The northeastern portion of the park is a special protected area, unfortunately off-limits to public visitation, that supports a significant portion of the remaining Maui Parrotbill and Akohekohe populations.

As recently as the 1990s, this remote area seemed to hold some prospect of preserving four species that are now almost certainly extinct: Bishop’s O’o, Po’o-uli, Maui Nukupu’u, and Maui Akepa. Each of these species is mysterious in its own way, and among them only the Po’o-uli was incontrovertibly present in eastern Maui in the late 1900s. The likelihood of rediscovering any of these is minuscule, although hopes for the Maui Akepa might run slightly higher because the species may have been somewhat nomadic and its voice was not well-documented, which makes it at least conceivable that past surveys could have overlooked a surviving population.

Akohekohe is rare in the publicly accessible portions of Haleakala National Park. © Jim Denny

Haleakala Crater. © sightalks

Notes

When to Visit

To find Hawaiian Petrels nesting, visit between early March and mid-August.

Hazards & Hassles

Haleakala National Park has seen its share of hiking trips that had unnecessarily tragic endings. A hike across the crater may seem straightforward enough, but with inadequate preparation (especially water) it can be a one-way trip.

Links