Cape Hatteras, North Carolina

The tip of Hatteras Island is a strategic location for bird diversity. It projects farther away from the continental coast than any other island on the East Coast, it holds the only significant tract of woodland along the Outer Banks, and it is where the warm Gulf Stream current meets the cold Labrador Current. Its location exceptionally combines terrestrial with oceanic and northern with southern influences, bringing warblers and shearwaters together, along with representatives of arctic, temperate, and tropical domains.

Orientation

Directions

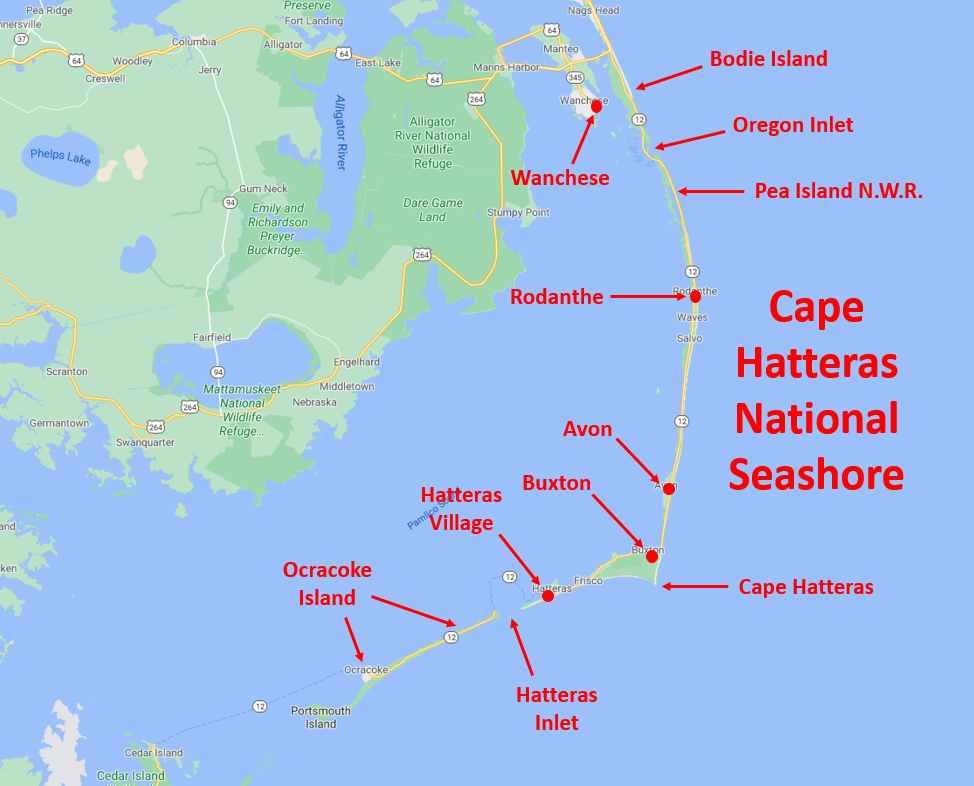

Cape Hatteras is the southeastern elbow projection of Hatteras Island on North Carolina’s Outer Banks, about an hour’s drive (50 miles) south of Nags Head, two hours and 40 minutes (130 miles) south of Norfolk, Virginia, and six hours (330 miles) south of Washington, D.C.

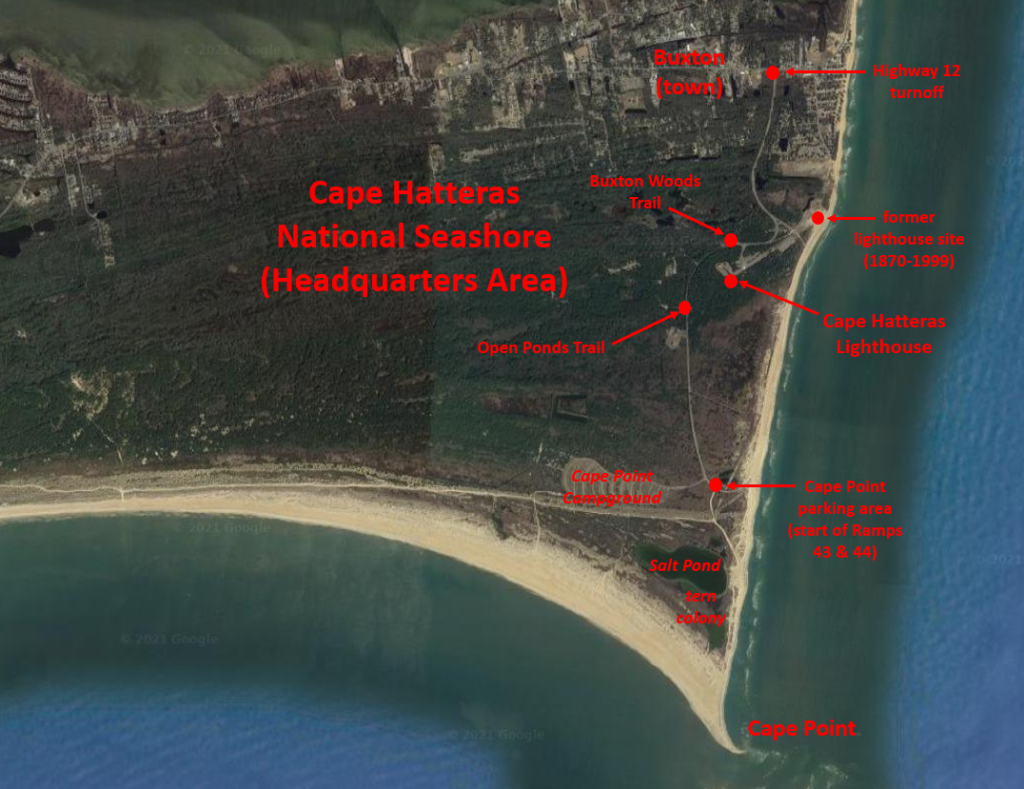

Follow NC Highway 12 south to Buxton, where the highway makes a wide 90-degree bend to west. At the end of this bend on the left (south) side of the highway are two Lighthouse Roads—the first is Old Lighthouse Road and the second is just Lighthouse Road. The latter is the entrance to the headquarters area of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, as the prominent signs indicate.

Attractions

Cape Hatteras is approximately 12 miles east of Hatteras Village, which is the departure port for deep-sea fishing and pelagic birdwatching trips in the Gulf Stream.

Birdfinding

Cape Hatteras National Seashore encompasses a very large portion of the Outer Banks, stretching from the southern boundary of Nags Head on Bodie Island south to Ocracoke Inlet. Birdlife is interesting throughout this extensive natural area, but the peak of its diversity is in the vicinity of Cape Hatteras itself, at the elbow of Hatteras Island, where the Gulf Stream meets the “Virginia Drift” (a vestige of the Labrador Current), and where the island is widest and most heavily wooded.

From the Highway 12 turnoff to the cape itself (i.e., Cape Point) is about 3.5 miles. The first 2.5 miles are on Lighthouse Road, which is paved to the Cape Point parking area. The last mile is dirt, gravel, or sand, which can be driven in a high-clearance vehicle or hiked.

The most obvious landmark along the road is the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the 200-foot-tall, black-and-white-striped pillar which is the only structure on Hatteras Island that pokes above the horizon and can be seen from long distance. The lighthouse area includes a visitor center and the Museum of the Sea, housed in a historical lighthouse keeper’s residence. Access to this compound is via a side-road 0.9 miles south of the Highway 12 turnoff.

Points that are generally of greater interest for birds and nature exploration include: the Old Lighthouse Area, Buxton Woods Trail, Open Ponds Trail, Cape Point Campground, and Salt Pond.

Entrance Road: The first mile of Lighthouse Road south from Highway 12 passes through a mixture of habitats that include marshes, fields, brush, low woodland, and ponds. Great Crested Flycatcher breeds in this area.

At around 0.6 miles, where the road passes through a wetland complex, a fairly large pond on the eastern side of the road often holds a few waterbirds, mostly in winter, regularly including Gadwall, American Black Duck, Redhead, Ring-necked Duck, Bufflehead, Pied-billed Grebe, and American Coot.

Old Lighthouse Area: About 0.8 miles from the highway, a side-road leads to the site where the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse stood from 1870 until 1999 (when it was relocated to avoid a gradual collapse into the ocean). The side-road forks, leading to two parking areas. The one on the left (north) is closer to the old lighthouse site.

Northern Gannet is common at Cape Hatteras from October to May. © Andrew Rapp

The beach can be good for coastal seabirds, especially in winter, when Northern Gannet is common. Beside the old lighthouse site, an erosion-control groin that extends out from the beach has a history of attracting winter rarities including Harlequin Duck, King Eider, Common Eider, Red-necked Grebe, Purple Sandpiper, Thick-billed Murre, Razorbill, and Little Gull.

Buxton Woods Trail: Just past the previous fork, on the right side of the road is a small parking area and the head of the Buxton Woods Trail. The three-quarter-mile loop winds through stunted island forest, and is generally most interesting in spring and fall when migrant landbirds can be numerous. In summer, the heat, humidity, and mosquitoes can severely degrade the hiking experience.

Palm Warblers winter along the seashore at Cape Hatteras. © Sue Barth

The trail is especially good for migrant warblers from late September into October, with the following species all regular: Ovenbird, Northern Waterthrush, Black-and-white, Common Yellowthroat (year-round), American Redstart, Cape May, Northern Parula, Magnolia, Blackpoll, Black-throated Blue, Palm, Pine, and Myrtle. Chuck-will’s-widow is found surprisingly often during May and June.

Open Ponds Trail: After another 0.2 miles another inland hiking trail begins at the World War II British Sailor Cemetery. The Open Ponds Trail heads west for about 1.5 miles, ending at a wetland. White-eyed Vireo and Pine Warbler breed in this area, and the latter is present year-round.

White-eyed Vireos breed along the Open Ponds Trail at Cape Hatteras. © Mike Stewart

Cape Point Campground: Just before the main road ends, a side-road on its western side leads to a large open campground. There is a guard-shack and gate, but access is controlled only during certain times of year, mainly summer. In the colder months the campground is typically closed to camping but open to explore. In March and April, especially after heavy rains, King Rail and Sora can often be found in the swales, and during fall and winter American Pipit and Palm Warbler are often present.

Salt Pond: The most reliably productive location at Cape Hatteras is the large pond just inland from Cape Point, south of the campground and west of the off-road vehicle route called Ramp 44. For a few months each summer, access is restricted to protect a substantial tern nesting colony—the location and extent of the colony and access restrictions vary, but nesting activity is usually concentrated on the southwestern side of the pond. At these times the viewing conditions are often suboptimal, but at other seasons the pond can be approached at various points on all sides.

The main nesting species are Least, Gull-billed, Common, Royal, and Cabot’s Terns, plus Black Skimmer. Non-nesting tern species that occur regularly in late summer include Caspian, Black, and Forster’s. Local tern diversity is occasionally augmented by vagrants, which have included Sooty, Bridled, White-winged, Roseate, and Arctic. A few shorebirds also breed along with terns: American Oystercatcher, Killdeer, and Piping Plover.

Black Skimmers nest among the terns at Cape Point. © Eric Carpenter

Over the course of the year, many other waterbirds visit the pond, including many species of waterfowl, waders, shorebirds, and gulls.

Cape Point: The tip is about one mile south of the Cape Point parking area. The most direct route is Ramp 44, which begins as a hard-packed gravel road, but transitions to sand partway to the beach. It is also possible to reach the tip by walking east from the parking area directly to the beach, then walking south—slightly longer, with the advantage of being on the beach.

Depending on the time of year and weather, the immediate vicinity of the point is among the best seawatching points along the Eastern Seaboard. Northern Gannet occurs regularly from October to May. Parasitic Jaeger is fairly common in April and May. In the summer months, Wilson’s Storm-Petrel and Sooty and Cory’s Shearwaters are seen fairly often when the conditions are favorable.

Only recently recognized as a separate species, Scopoli’s Shearwater likely occurs regularly at Cape Hatteras but has been overlooked due to its similarity to Cory’s Shearwater. © Steve Kelling

Pelagic birds approach within view of the shore most consistently in late May, the local peak of northbound seabird migration. A glance at a regional map will make the primary reason for this apparent: a bird migrating north over waters of the Georgia Bight would come ashore southwest of Cape Hatteras unless they turn east, so the coastline has a funneling effect that tends to channel oceanic species along the southern Outer Banks and concentrate them at Cape Point.

In winter the local gull flock often includes one or more uncommon species such as Little, Black-headed, Iceland, or Glaucous. Razorbill occurs regularly from January to April. Some winters bring flights of Dovekie, and Atlantic Puffin is sporadic.

Services

Accommodations

In Buxton:

Cape Pines Motel, 1-252-995-5666

Cape Hatteras Motel, 1-252-995-5611

Hatteras Island Inn, 1-252-995-6100

Lighthouse View Motel, 1-252-995-5680

Outer Banks Motel, 1-252-995-5601

Notes

When to Visit

Cape Hatteras can be rewarding to visit at any time of year. While most tourists visit in the summer, the other seasons have at least as much potential for interesting birds. For example, the depths of winter bring alcids and rare gulls, spring brings pelagic species close to shore, and fall brings migrant landbirds offshore.

Links