Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common and widespread in grassy areas near water throughout most of India east to West Bengal. Generally uncommon and localized elsewhere. Near Bangkok, one place where it can often be found is Lat Krabang. In northern Thailand, the campuses of Mae Jo University and Mae Hia Agricultural College in Chiang Mai are consistent sites. In Fiji, it is common around Nadi; in Portugal, at Barroca d’Alva and Herdade da Alfarófia; in Spain, at Badajoz, Madrigalejo, Montehermoso, and Soto Gutiérrez; and on Guadeloupe, at Barrage de Gaschet. In Hawaii, it is common in the lowlands of Oahu (e.g., Kapolei, Honouliuli, Kawainui, and James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge) and Kauai (Poipu and Lihue Airport), but less so on the Big Island (where Kealakehe Wastewater Treatment Plant, Pu’u Anahulu, and the end of Waikoloa Road are consistent sites).

Red Avadavat

Amandava amandava

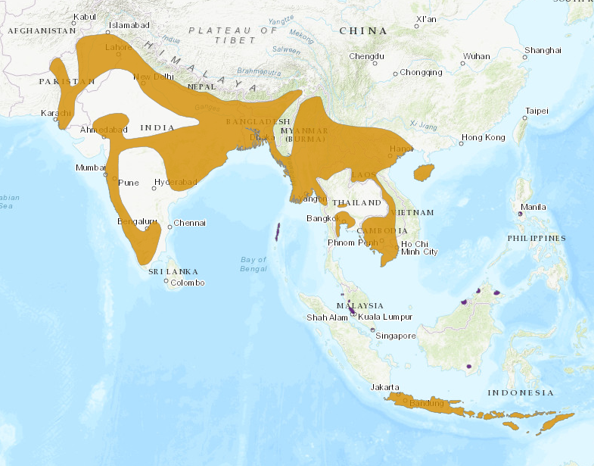

Southern Asia and Indonesia; widely introduced elsewhere. Occurs in open grassy habitats, usually near water and often in marshes, mainly in humid lowlands, but locally up to 2,400 m elevation.

Approximate natural range of the Red Avadavat (with some sites of reported introduced populations shown in purple). © BirdLife International 2016

In South Asia, widespread across the subcontinent from northeastern Pakistan east across most of India, the Nepalese lowlands, and Bangladesh—but not in Sri Lanka.

In Southeast Asia, local in valleys and plains of Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia. Also occurs very locally in adjacent portions of western Yunnan, southwestern Laos, and southern Vietnam.

In Indonesia, found on Java, Bali, Lombok, Flores, Sumba, Roti, Alor, Timor, and Wetai—but apparently not on Sumbawa (between Lombok and Flores).

Widely introduced worldwide, with significant populations established in several areas, including: central and southern Portugal and Spain; along the Nile River in Egypt; Singapore; Fiji (several islands); and Hawaii (Kauai, Oahu, and the Big Island).

Smaller populations appear to be established in: northern Italy (near Pisa); northeastern Greece (around Lake Ismarida); Saudi Arabia (Riyadh area); the United Arab Emirates (Dubai area); peninsular Malaysia (Penang); northern Borneo (Sabah); Guadeloupe; and possibly also Martinique.

Populations currently designated as A. a. flavidiventris (and sometimes as the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat”) occupy two disjunct areas: northern Indochina (most of Myanmar and adjacent portions of China and northern Thailand) and the Lesser Sundas (from Flores to Timor). (See Notes below, Frontiers of Taxonomy: Why the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat” Is Probably a Color Morph, Not a Distinct Taxonomic Form.)

Identification

Male in breeding plumage is unique: vivid red overall, with a rosy bill and brown wings, back, and tail, and dappled with crisp, white specks on the wings, sides, chest, rump, and tail.

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage showing black lores and white crescent below the eye. (Rajarhat Wetlands I, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, India; October 2, 2018.) © Souvik Roychoudhury

Often has black lores and a fine white crescent below the eye. The belly and vent are blackish throughout most of its range, but in the “Yellow-bellied” populations of northern Indochina and the Lesser Sundas, the male’s belly is paler, shading from orange to yellow.

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage, ventral view showing blackish belly and white specks across chest. (Bangalore, India; September 11, 2016.) © Shreyan M.L.

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, male in breeding plumage. (Nam Kham Nature Reserve, Chiang Rai, Thailand; December 4, 2018.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage. (New Mumbai, Maharashtra, India; October 12, 2017.) © Mayureshl Khatavkar

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage showing black lores and belly. (Pariej Lake, Kheda, Gujarat, India; December 19, 2015.) © Manish Panchal

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage. (Lat Krabang, Bangkok, Thailand; January 21, 2018.) © Bird Soong

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage with limited white speckling. (The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India; August 26, 2017.) © Renuka Vijayaraghavan

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage with limited white speckling—note that this bird has a black belly and is in the range of the putative “Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris. (Mae Jo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; September 4, 2018.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage with large white spots. (Kotagiri, Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu, India; October 10, 2019.) © Manjula Mathur

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage, appearing darker and browner than most. (Naihati, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, India; October 6, 2019.) © Nikhil Adhikary

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, male in breeding plumage. (Nam Kham Nature Reserve, Chiang Rai, Thailand.) © Woraphot Bunkwhamdi

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage—note that this photo was taken along India’s western coast, far from the range of the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris. (Ganeshghat, Dombivli, Thane, Maharashtra, India; November 22, 2018.) © Sujata Phadke

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage, dull brownish-red overall. (Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India; May 15, 2012.) © Jugal Tiwari

Red Avadavat, moulting male. (Ganeshghat, Dombivli, Thane, Maharashtra, India; March 28, 2019.) © Sujata Phadke

Red Avadavat, male. (Soto Gutiérrez, Sureste Nature Park, Madrid, Spain; March 29, 2019.) © José Martín

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, moulting male. (Sumba, Indonesia, Indonesia; July 23, 2018.) © Yovie Jehabut

Red Avadavat, moulting male. (Hosakote Kere, Bangalore, Karnataka, India; March 10, 2018.) © Sivaguru Noopuran PRS

Red Avadavat, moulting male. (Deobali Jalah, Nagaon District, Assam, India; February 27, 2018.) © Sapon Baruah

Red Avadavat, male in nonbreeding plumage with a few red feathers on the nape. (Punjab, Pakistan; December 25, 2017.) © Imran Shah

Female is brownish above and paler below, with a vivid red rump, rosy or dark bill, a black mask, and crisp, white speckles on the wings and tail.

The upperparts vary in tone from grayish to olive, and the underparts vary from gray or tan to yellow—females of the “Yellow-bellied” populations tend to be more olive above yellower below than the others

Red Avadavat, female. (Hazratpur Wetlands, Bareilly District, Uttar Pradesh, India; September 3, 2016.) © Kaajal Dasgupta

Red Avadavat, female with extensively yellowish underparts. (Dankuni Wetland, Hooghly District, West Bengal, India; September 2, 2018.) © Santanu Chatterjee

Red Avadavat, female. (Rampura Grassland, Dahod District, Gujarat, India; December 1, 2017.) © Pragnesh R. Patel

Red Avadavat, female with extensively yellowish underparts. (The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India; August 12, 2018.) © Renuka Vijayaraghavan

Red Avadavat, female with predominantly gray plumage. (Dhanauri Wetlands, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India; April 19, 2018.) © Vijay Kumar Sethi

Red Avadavat, pale female with crisp black mask. (Pashchim Medinipur, West Bengal, India; September 23, 2016.) © Sourav Dinda

Red Avadavat, female with predominantly drab brown-and-gray plumage. (Hoskote Lake, Bangalore, India; January 26, 2016.) © Sachin Shurpali

Red Avadavat, female appearing mostly plain and nondescript. (Ban Khum fish ponds and paddies, Phetchaburi, Thailand; January 20, 2016.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Red Avadavat, female with plain-gray underparts. (Herdade da Alfarófia, Elvas, Portalegre, Portugal; April 23, 2012.) © Jorge Safara

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, female showing predominantly olive plumage. (Bulong Prefectural Nature Reserve, Mengsong, Yunnan, China; February 1, 2012.) © Craig Brelsford

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, female showing predominantly olive plumage. (Nam Kham Nature Reserve, Chiang Mai, Thailand.) © Woraphot Bunkwhamdi

Red Avadavat, female preening its rump. (Garden of the Sleeping Giant, Nadi, Vitu Levu, Fiji; March 3, 2018.) © David Irving

Immature is brownish with a dark bill, buffy wingbars, and often pale eye-crescents and white margins on the outer tail feathers.

Red Avadavat, immature. (Abhera Wetland, Kota, Rajasthan, India; November 26, 2011.) © Sunil Singhal

Red Avadavat, immature with a generally sooty appearance. (Okhla Bird Sanctuary, Uttar Pradesh, India; December 30, 2019.) © Srikumar Bose

Red Avadavat, immature with a pinkish bill, bold white eye-crescents, strong wingbars, and upright, flycatcher-like posture. (Abhera Wetland, Kota, Rajasthan, India; November 26, 2011.) © Sunil Singhal

Red Avadavat, immature. (Chilla Khader, Delhi, India; February 13, 2019.) © Rajeth Kalmar

Red Avadavat, immature. (Bhandup Pumping Station, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India; January 30, 2016.) © Avinash Bhagat

Red Avadavat, immature, dorsal view showing a mostly drab, nondescript small songbird, lacking any notable features. (University of Hawaii – West Oahu, Kapolei, Hawaii; March 9, 2018.) © Sharif Uddin

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of three recognized subspecies, amandava, punicea, and flavidiventris (the latter sometimes considered a distinct form, the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat”; see “Notes”).

Alternative names include Red Munia and Strawberry Finch (traditional among aviculturists).

Frontiers of Taxonomy: Why the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat” Is Probably a Color Morph, Not a Distinct Taxonomic Form.

Whereas most male Red Avadavats have extensively black bellies, in two widely separated portions of its range, northern Indochina and the Lesser Sundas of Indonesia, the males have mostly yellow-to-orange bellies. These populations are recognized as a single subspecies, A. a. flavidiventris, often referred to as the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat.” They are visually distinctive (males more so than females) and have received some attention as a potential candidate for full species status, but the available evidence suggests that these are regional variants or color morphs of Red Avadavat, not an independent branch of the taxonomic tree.

Red Avadavat, typical black-bellied male in breeding plumage. (Rajarhat Wetlands I, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, India; October 2, 2018.) © Souvik Roychoudhury

“Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris, male in breeding plumage. (Nam Kham Nature Reserve, Chiang Rai, Thailand; December 4, 2018.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

The basic observation that points to this conclusion is biogeographic: the Red Avadavat’s natural range (as it is understood) consists of two widely separated regions (southern Asia and parts of Indonesia) and both regions have black-bellied and yellow-bellied populations in them. To draw a taxonomic distinction between black-bellied and yellow-bellied “forms”—i.e., as separate species or incipient species—would entail that the two sets of yellow-bellied populations are more closely related to one another than to the adjacent black-bellied populations. But their peculiar distribution makes this appear unlikely (conceivable, but unlikely).

Based on our understanding of speciation, the current distribution of black-bellied and yellow-bellied populations could have three possible origins: (1) the widespread ancestral species was black-bellied and an isolated population developed yellow bellies; (2) the widespread ancestral species was yellow-bellied and an isolated population developed black bellies; or (3) the widespread ancestral species was black-bellied and two isolated populations developed yellow bellies. Each of the possible origins raises its own peculiar set of implications.

Single split from black to yellow: If the common ancestral stock was black-bellied and a yellow-bellied population developed—presumably in either northern Indochina and the Lesser Sundas—it is difficult to imagine the sequence of historical events that would result in the current distribution.

The regions of northern Indochina and the Lesser Sundas are approximately 2,000 miles apart, with the expanse between them partly occupied by two different black-bellied populations, partly unoccupied, and partly ocean. A complex and fortuitous—and ultimately implausible—progression of range expansions and contractions would be needed for an initially isolated yellow-bellied population to bridge this gap naturally without being reabsorbed into the black-bellied majority. Human-assisted transport is a theoretically possible explanation, but the remoteness of both areas makes this seem highly unlikely as well.

Single split from yellow to black. A somewhat more plausible scenario is that the common ancestral stock was yellow-bellied and a black-bellied population developed. In this scenario, the development of black bellies could have occurred anywhere in the ancestral range—probably on the Indian subcontinent, in light of the Red Avadavat’s current distribution.

This hypothesis raises a different set of problematic issues, however, because it would mean that black-bellied populations displaced the yellow-bellies from an originally wider range, leaving two isolated remnants. This in turn implies that black-bellies outcompete yellow-bellies either genetically (through sexual selection) or ecologically (through some other trait).

While it is conceivable that black-bellies do in fact hold an evolutionary advantage over yellow-bellies, the existence of such an advantage, by itself, would not explain the current distribution. If true, this hypothesis implies that yellow-bellied populations require a physical or ecological barrier against invasion by black-bellies—which exists in one case but not the other.

Red Avadavat, black-bellied male in breeding plumage—photograph taken within the range of the putative “Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris. (Mae Jo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; September 4, 2018.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

The Lesser Sunda populations are naturally isolated by water: there are black-bellied populations on Bali and Lombok in the western Lesser Sundas, across the Alas Strait from Flores. But the continental Indochinese population is wedged between two black-bellied populations that occur in the same habitat and biome as the yellow-bellied, with no apparent isolating factor. In fact, they clearly are not isolated as black-bellied males occur together with yellow-bellied males in northern Thailand (and probably Myanmar, etc.).

Two independent splits from black to yellow. Lacking a plausible theory to explain how a single split progressed to the peculiar distribution pattern of yellow-bellied and black-bellied populations that prevails today, the straightforward explanation is that the yellow-belly trait emerged independently in northern Indochina and the Lesser Sundas.

A likely implication is that this difference in belly pigmentation is part of the natural variation within Amandava amandava. It may either be a latent trait or caused by a simple mutation that recurs from time to time, which in two extant cases became locally predominant. There is some evidence to support this—as some males in black-bellied populations have yellow bellies.

Red Avadavat, male in breeding plumage—photograph taken along India’s western coast, far from the range of the “Yellow-bellied Avadavat,” A. a. flavidiventris. (Ganeshghat, Dombivli, Thane, Maharashtra, India; November 22, 2018.) © Sujata Phadke

With this explanation it seems appropriate to regard the yellow-bellied populations as regional color morphs of Red Avadavat, pending the emergence of new information that supports separate status for either or both of them. Finally, if they are recognized as subspecies—i.e., separate lineages on the avadavat family tree—they would have to be two, not one, so the designation flavidiventris should not include both of them.

References

Anonymous. 2018. Amandava amandava (Linnaeus, 1758) – Red Munia. Birds of India Consortium (eds.). Birds of India, v. 1.56. Indian Foundation for Butterflies. http://www.birdsofindia.org/sp/1382/Amandava-amandava. (Accessed April 14, 2018.)

BirdLife International. 2016. Amandava amandava. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22719614A94635498. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22719614A94635498.en. (Accessed March 29, 2020.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Clement, P., A. Harris, and J. Davis. 1993. Finches and Sparrows: An Identification Guide. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed March 30, 2020.)

Hawaii Audubon Society. 2005. Hawaii’s Birds (Sixth Edition). Island Heritage Publishing, Waipahu, Hawaii.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

National Institute for Environmental Studies, Invasive Species of Japan, Amandava amandava. https://www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/detail/20260e.html. (Accessed April 14, 2018.)

Payne, R. 2018. Red Avadavat (Amandava amandava). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://www.hbw.com/node/61081. (Accessed March 30, 2020.)

Pratt, H.D. 1993. Enjoying Birds in Hawaii: A Birdfinding Guide to the Fiftieth State (Second Edition). Mutual Publishing, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii. http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Restall, R. 1997. Munias and Mannakins. Yale University Press, New Haven.