Birdfinding.info ⇒ The Salmon-crested Cockatoo is a charming, charismatic species, which is therefore among most severely persecuted for the illegal cagebird trade, and is becoming endangered as a result. (See Notes below: Illegal Capture and Trade Threatens the Salmon-crested Cockatoo’s Survival as a Wild Species.) Sites where it has traditionally been present include Manusela National Park on Seram and the Hitu Peninsula on Ambon, but it may be now or soon extirpated from the latter. It reportedly remains locally common in remote valleys of eastern Seram. On Oahu, an escaped flock has inhabited the Lyon Arboretum and nearby Manoa Valley since the 1970s.

Salmon-crested Cockatoo

Cacatua moluccensis

Endemic to the southern Moluccas: Seram and its southwestern satellite islands, Ambon, Haruku, and Saparua. Apparently extirpated from Haruku and Saparua, and nearly eliminated from Ambon, so effectively endemic to Seram.

Occurs in all forest types, from lowlands up to around 1,200 m elevation. Most numerous in rainforest at lower elevations (<180 m).

A small flock of escaped cockatoos has inhabited Honolulu’s Manoa Valley, mainly around Lyon Arboretum, since the early 1970s. Of the six species reliably reported, this or Sulphur-crested have predominated at different times—the trend since 2000 has been toward Salmon-crested, reaching an apparent maximum of eight birds. Members of the flock have been observed breeding (and hybridizing) so it is at least partly self-sustaining.

Identification

A distinctive large white, or whitish, cockatoo with a luxuriant pink-and-white crest: a white shield with pink feathers behind it.

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; April 25, 2015.) © Colin Morita

The tone, extent, and vividness of the pink in its crest varies. At rest, the white shield mostly obscures the pink feathers, so it can appear all-white under some conditions.

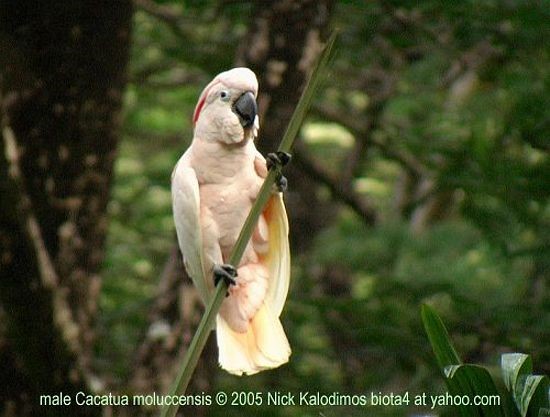

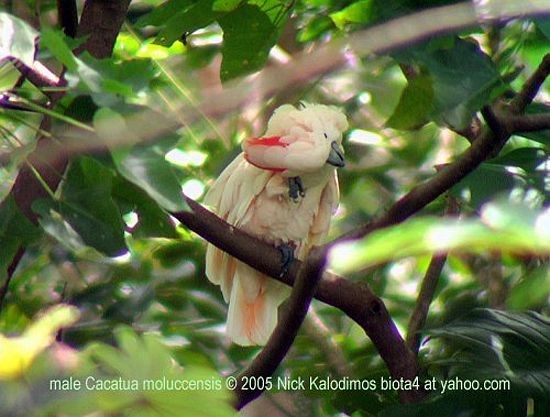

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Southern Moluccas, Indonesia; 2005.) © Nick Kalodimos

The body plumage in general is often suffused with a pinkish blush, which often shades to orange or yellow, especially on the belly and sometimes on the tail.

Salmon-crested Cockatoo—can appear nearly all-white under some conditions. (Southern Moluccas, Indonesia.) © Phillip Edwards

Salmon-crested Cockatoos, pair-bonding. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; August 19, 2019.) © Kimberly Jeffries

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, showing a generally pinkish blush throughout its plumage. © Giuseppe Mazza

Salmon-crested Cockatoo—an isolated feral individual—dorsal view in flight, showing a generally pinkish blush throughout its plumage. (Hong Kong Park, Hong Kong; March 9, 2008.) © Martti Siponen

The undersides of the wings and tail typically have a colorful wash that can be either pinkish-orange or yellowish.

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, ventral view in flight showing pinkish-orange wash. (Southern Moluccas, Indonesia.) © Phillip Edwards

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, ventral view in flight showing yellowish wash. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; November 17, 2006.) © Michael Walther

Voice. Typical calls are brief whoops, yelps, and yips that typically fall and fade out. Most calls have a quality that resembles electrical amplification: Seram, Indonesia; March 13, 1998. © Frank Lambert

A common variation is a reverberating trill: Seram, Indonesia; May 16, 1998. © Frank Lambert

Such trills sometimes rise to the level of screams: Solea Village, Seram, Indonesia; July 2, 1994. © Filip Verbelen

Sometimes gives individual notes and sometimes raises a raucous, insistent racket, often with multiple individuals, loud enough to be heard at a distance of >1 km: Seram, Indonesia; May 16, 1998. © Frank Lambert

Notes

Monotypic species.

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable.

See below for a comparison of Salmon-crested Cockatoo with White Cockatoo, and a note on its conservation status: Illegal Capture and Trade Threatens the Salmon-crested Cockatoo’s Survival as a Wild Species.

Cf. White Cockatoo. White and Salmon-crested Cockatoos are sibling species that are endemic to nearby island groups in the Moluccas—White to the Bacan Islands and Salmon-crested to Seram and its neighbors. They do not occur together naturally, but because both are popular cagebirds both have been found living ferally outside of their natural ranges, often in the same areas (e.g., Hawaii and Puerto Rico). Moreover, it appears that they may have hybridized at least once in Hawaii, potentially producing intermediate offspring.

They are approximately the same size, with similarly-shaped crests and similar coloration. The White Cockatoo is nearly all-white (with yellowish underwings and undertail) and Salmon-crested usually has a pinkish tone in its coloration (with pinkish, orangish, or yellowish underwings and undertail), but the tones of both species vary and viewing conditions make subtle differences in tone unreliable for identification. The only consistent difference is the presence or absence of pink in the crest—however, this is sometimes concealed, and hybrid offspring are also likely to show some pink in the crest, so even the crest coloration is somewhat unreliable for identification.

Salmon-crested Cockatoo (at left) with a White Cockatoo preening it—apparently a mated pair. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; August 16, 2018.) © Walter Oshiro

Illegal Capture and Trade Threatens the Salmon-crested Cockatoo’s Survival as a Wild Species. According to IUCN: “By the 1980s the species was being extensively and unsustainably trapped for the cage-bird market, with an estimated 74,509 individuals exported from Indonesia between 1981 and 1990, and international imports averaging 9,751 per annum between 1983 and 1988. Although reported international trade fell to zero in the 1990s, trappers have remained highly active and birds are openly sold within Indonesia. This illegal trade was prolific during religious riots in 2004, and baseline estimates suggest 4,000 birds are removed from the wild annually in domestic trade. Commercial timber extraction, settlement and hydroelectric projects, pose the other major threats through resultant forest loss and fragmentation. It is predicted that half the current population on Seram may be lost to conversion of forest in the next 25 years. Most forest has already been lost from Ambon and the coasts and lowlands of Seram. It has also been considered a harmful pest to coconut palms, and, historically at least, it was consequently persecuted.” (BirdLife International 2016 (internal citations omitted))

Additional Photos of Salmon-crested Cockatoo

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; September 10, 2018.) © Bradley Hacker

Salmon-crested Cockatoos, pair-bonding. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; February 22, 2019.) © Walter Oshiro

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, showing its pink crest from above. (Southern Moluccas, Indonesia; 2005.) © Nick Kalodimos

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, stretching and showing its underwing. (Southern Moluccas, Indonesia; 2005.) © Nick Kalodimos

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; September 10, 2018.) © Bradley Hacker

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; September 25, 2018.) © Kathryn Hart

Salmon-crested Cockatoo—an isolated feral individual. (Las Piñas-Parañaque, Luzon, Philippines; May 4, 2019.) © Robert Hutchinson

Salmon-crested Cockatoo—an isolated feral individual. (Las Piñas-Parañaque, Luzon, Philippines; March 14, 2021.) © Mike Lu

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; October 18, 2019.) © Scott Berglund

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; May 22, 2018.) © Walter Oshiro

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; May 10, 2018.) © Walter Oshiro

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; November 17, 2006.) © Michael Walther

Salmon-crested Cockatoo. (Lyon Arboretum, Honolulu, Hawaii; July 31, 2018.) © Walter Oshiro

Salmon-crested Cockatoo, ventral view in flight appearing orangish-brown—possibly an artifact of the lighting. (Sawai, Seram, Indonesia; August 1, 2009.) © Jon Hornbuckle

References

BirdLife International. 2016. Cacatua moluccensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22684784A93046425. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22684784A93046425.en. (Accessed May 31, 2020.)

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed May 30, 2020.)

Forshaw, J.M. 2010. Parrots of the World. Princeton University Press.

Juniper, T., and M. Parr. 1998. Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World. Yale University Press.

Michigan State University. 2020. AVoCet: Avian Vocalizations Center. https://avocet.integrativebiology.natsci.msu.edu/. (Accessed May 31, 2020.)

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.