Frontiers of Taxonomy: Are We Splitting the Lesser Antillean Tanager?

In 2016, BirdLife International and the Handbook of the Birds of the World reclassified the Lesser Antillean Tanager (Tangara cucullata, or alternatively Stilpnia cucullata) as two species: the “Grenada Tanager” (cucullata) and the “St. Vincent Tanager” (versicolor). The 2019 field guide Birds of the West Indies also adopted the split, but as of 2021 the more conservative American Ornithological Society had not. For reasons explained below, a species-level split seems premature, and should probably be reconsidered pending more conclusive evidence that the two forms have in fact diverged, or that they have not.

The Differences Are Noticeable but Inconclusive. The Handbook based its determination on four cited differences in plumage plus a size difference. It stated that in comparison to “Grenada”, “St. Vincent” differs in having: (1) in males, a pale chestnut or rufous crown, rather than chocolate-brown; (2) more of a russet wash on its bluish underparts; (3) a buffier, less greenish tone on the hindcollar, mantle, back and rump; (4) a bluer tinge to its pale turquoise-green wing fringes and tail fringes; and (5) larger size, most notably of the bill. The authors prioritized the males’ crown color and bill size as more significant than the other differences.

“St. Vincent Tanager,” T. c. versicolor, male showing its rufous crown and blue wings. (Vermont Nature Trail, St. Vincent; February 23, 2014.) © Stephen Gast

“Grenada Tanager,” T. c. cucullata, male showing its chocolate-brown crown and turquoise-green wings. (Morne Jaloux, Grenada; February 21, 2020.) © Dennis S. Main

There is no uniform, universally agreed-upon standard for deciding when a set of observed differences or underlying genetic differences become sufficient to decide that two closely related forms such as these should be regarded as separate species, and the general consensus among taxonomists is undergoing a long-term shift toward recognizing more diversity. The outward differences between “Grenada” and “St. Vincent” fall somewhere in the marginal zone between ambiguous and definitive—making them at least recognizably distinct forms and plausibly separate species.

“Grenada Tanager,” T. c. cucullata, female showing maximally green coloration and crown appearing dark-brown (likely due at least in part to the lighting). (St. David, Grenada.) © Bela Lucia

The crown color of the males appears to be a consistent and observable distinction, perhaps the only distinction yet described that would be sufficient to confidently identify an individual as one form or the other outside of its expected range. The tones of the males’ body plumage, wings, and tail might also differ consistently, but a range of variation is noticeable within both forms and may exceed the distinctions between them. The reported bill size differential is not readily noticeable, and seems questionable as a distinction.

The Problem: Not Enough Separation for Speciation. Viewed through the lenses of biogeography and evolution, these forms appear to lack the historical conditions of long-term reproductive isolation that would lead them to diverge as separate species through genetic drift. Although St. Vincent and Grenada are separated by sixty miles of ocean, the Grenadine chain provides a stepping-stone bridge, and at least one—and possibly both—of the forms occurs either regularly or sporadically on some of the islands in between.

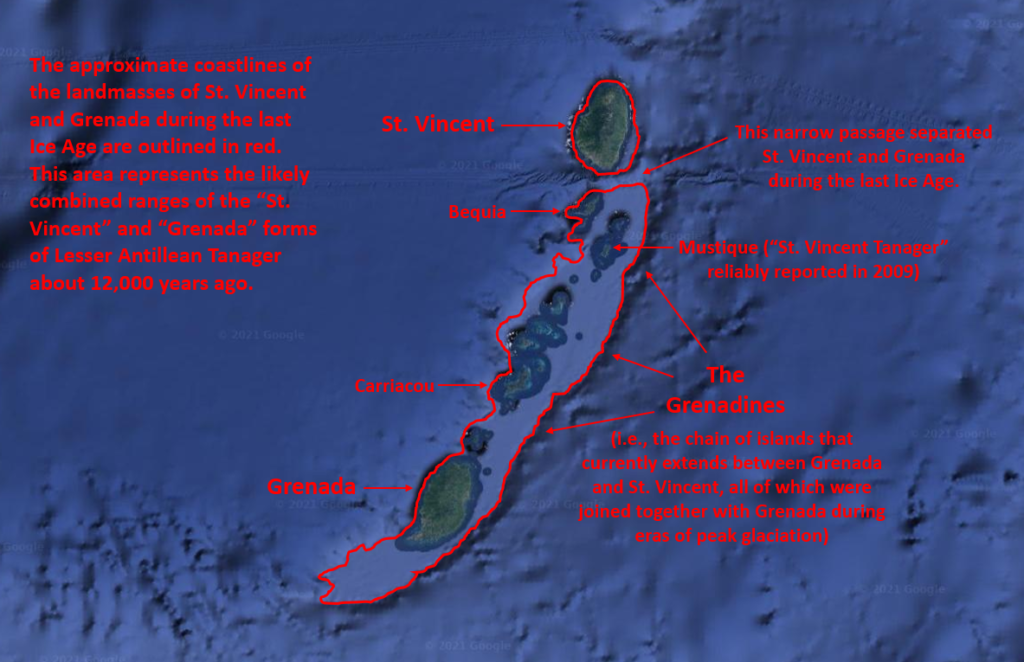

Within the past 12,000 years, at the latest peak of glaciation, the Grenadine land-bridge was almost completely dry, with a gap of about three miles between St. Vincent and what is now known as Bequia (but was then the northern end of a much larger Grenada).

In recent years, the “St. Vincent” form has certainly occurred on both sides of that gap, as a mated pair was reliably reported on Mustique in 2009, and there is a 2014 record from the northern end of Bequia, approximately six miles from St. Vincent. Recent sightings reported from the central Grenadines (Union in 2015 and Mayreau in 2017) could refer to either form—note that the Union record was reported as a flock of eight.

Presumably a “Grenada Tanager” female, based on the location and its rufous crown, but with the buffy body plumage of a male (or could this instead be this a male “Grenada Tanager” with atypical crown coloration, or either a male or female “St. Vincent Tanager” that wandered to the “wrong” island?). (St. David, Grenada.) © Bela Lucia

Both forms are habitat generalists that regularly occur at sea level and do not seem averse to island-hopping, so it is reasonable to infer that they were effectively a single population at least as recently as the last Ice Age. This suggests that the interruption of gene flow between the St. Vincent and Grenada populations is geologically recent—probably too recent to result in speciation through genetic drift.

Future Research Could Help Resolve This. There is an opening for research that would tend to support or refute the reclassification. In particular, it seems likely that a robust mitochondrial DNA analysis would corroborate—or possibly disprove—the biogeographical inference that their divergence began in the Holocene.

Secondarily, a potentially helpful field research project would be to experiment with playback of vocalizations. The results might have limited value, considering that the two forms have generally similar voices (compare recordings from Grenada, St. Vincent, and another from St. Vincent), and that Tangara tanagers elsewhere readily assemble into mixed-species flocks. Nevertheless, if both populations were found to exhibit clear, consistent responses or unresponsiveness to vocal triggers from the other population, such results could constitute strong evidence for one conclusion over the other.

The Handbook’s split of these closely related forms might be justified on grounds of recognizing and preserving biodiversity, and might ultimately be vindicated, but that assessment will require further research and analysis to account for the circumstantial indications that their divergence apparently began too recently to support reclassification as separate species.

References

BirdLife International. 2017. Tangara cucullata (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T103848963A119556420. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T103848963A119556420.en. (Accessed June 26, 2021.)

BirdLife International. 2017. Tangara versicolor (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T103848974A119558904. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T103848974A119558904.en. (Accessed June 26, 2021.)

del Hoyo, J., N. Collar, and G.M. Kirwan. 2019. Grenada Tanager (Tangara cucullata). In Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D.A. Christie, and E. de Juana, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://www.hbw.com/node/61700. (No longer available. Accessed November 19, 2019.)

del Hoyo, J., N. Collar, and G.M. Kirwan. 2019. St Vincent Tanager (Tangara versicolor). In Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D.A. Christie, and E. de Juana, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://www.hbw.com/node/1344199. (No longer available. Accessed November 19, 2019.)

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed June 26, 2021.)

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Text © Russell Fraker / June 26, 2021