Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common to locally abundant and spreading in many parts of its range. A familiar, confiding garden bird that is easily found at most heavily visited sites on the Mexican Riviera, the ABC Islands, St. Lucia, Grenada, the Grenadines, Tobago, coastal Colombia, and the Llanos. Also common in eastern Brazil, where populations are heavily associated with coastal scrub—its Portuguese name, Sábia-da-praia, means “beach thrush.”

Tropical Mockingbird

Mimus gilvus

Middle America, islands of the southern Caribbean, and northern and eastern South America, where it occurs mainly in semiopen habitats: scrub, open woodland, dry forest, and settled and agricultural areas.

Comprises two distinct forms, which were formerly regarded as separate species:

“Tropical Mockingbird” (gilvus): widespread, discussed in detail below.

“San Andrés Mockingbird” (magnirostris): endemic to Isla San Andrés in the southwestern Caribbean, discussed in detail here.

In the West Indies, on: the ABC Islands; several Venezuelan islands including La Orchila, Tortuga, La Blanquilla, Los Testigos, and Margarita; the Lesser Antilles from Antigua to Grenada; Trinidad; and Tobago. Has also occurred at least sporadically on Barbuda and Barbados (where previously introduced but no longer resident).

In Middle America, widespread from the Yucatán Peninsula southward, extending west of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to central Veracruz and central Oaxaca. Also resident or sporadic on many adjacent islands, including Holbox, Contoy, Mujeres, Cozumel, Chinchorro Bank, the Belizean cayes, and Roatán.

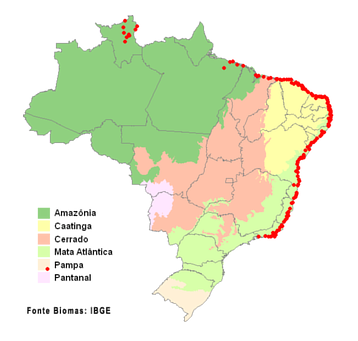

Brazilian records of Tropical Mockingbird, by municipality. © WikiAves 2021

In South America, from the Caribbean coast south to central Ecuador, the Llanos of Colombia and Venezuela, and the savannas of Roraima, east to French Guiana; and separately in the coastal zone of eastern Brazil from Pará to Rio de Janeiro.

Range Expansion. The large-scale clearance of humid forests has enabled dramatic range expansion in Central and South America. Until around 1990, it occurred naturally from southeastern Mexico to El Salvador and separately from northern and central Colombia eastward, while a small introduced population was established in central Panama. During the 1990s and 2000s, these populations spread to occupy all territories from Mexico to the Pacific lowlands of Colombia and northwestern Ecuador, and from the Llanos locally into Amazonian Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and northernmost Peru.

This Tropical Mockingbird was present at Lake Worth Beach Park in Palm Beach County, Florida for about three months in 2017, mated with a Northern Mockingbird. (July 9, 2017.) © Robert Qually

U.S. Records. Vagrants have been recorded twice in the U.S.: Port Arthur, Texas from April to June 2012, and Lake Worth, Florida from June to August 2017. Both individuals nested with Northern Mockingbirds, then vanished, and both were rejected by the respective state bird records committees on the basis of questionable provenance—i.e., the inferred likelihood that they had escaped from captivity instead of occurring naturally. (To the contrary, however, considering that both locations are near major ports and Tropical Mockingbird’s distribution entails regular dispersal over the sea, ship-assisted natural vagrancy would seem to be the presumptive default explanation for these records. Perhaps they will be reconsidered if this apparent pattern continues.)

Identification

Closely resembles its familiar North American relative, the Northern Mockingbird: gray overall with a long tail, often singing from low perches. (For a comparison of the two gray mockingbirds, see below.)

Tropical Mockingbird, showing typically pale-gray upperparts with blackish wings and tail. (Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, Mexico; January 7, 2021.) © Mark Goodwin

The upperparts are typically pale-gray with contrasting blackish wings and tail. Some are more medium-gray or brownish overall.

The underparts are whitish and mostly unmarked—but many have a few sparse blackish streaks on the flanks.

Tropical Mockingbird, comparatively brownish above and dingy below, with distinct streaks on the flank. (Parajuru, Ceará, Brazil; August 21, 2016.) © Caio Brito

The tail is mostly black with narrow white outer edges and broad white corners that are visible mainly when it is spread.

Tropical Mockingbird, showing mostly blackish, white-cornered tail and clean white underparts. (Mérida, Venezuela; January 31, 2015.) © Jose Ramon

Tropical Mockingbird, an atypically uniform-toned, washed-out individual. (Laguna Villa Royal, Sabana Grande, Honduras; December 17, 2015.) © Alfonso Auerbach

Facial markings vary from bold to subtle: a blackish eyestripe and whitish eyebrow. The bill is mid-sized (short compared to other thrashers), black, and slightly curved.

Tropical Mockingbird with dark upperparts, and showing streaks on the flank. (Baía Formosa, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; November 3, 2019.) © Roger Horn

Tropical Mockingbird with pale-gray upperparts, and showing white-cornered tail. (El Valle de Antón, Coclé, Panama; August 11, 2018.) © Paul Oehrlein

Immatures are usually browner or buffier than adults and have fine dark spots on the chest and flanks.

Tropical Mockingbird, juvenile showing fine streaking on breast and flank. (El Palmar, Panamá, Panama; March 23, 2014.) © Tim Avery

Tropical Mockingbird, juvenile showing fine streaking on breast and flank. (Camarones, La Guajira, Colombia; August 4, 2016.) © Neil Diaz

The highly localized “San Andrés Mockingbird” (magnirostris) averages about 10% larger than other subspecies and often has a proportionately longer and heavier bill.

“San Andrés Mockingbird”, M. g. magnirostris—in this view, showing the distinctive length and thickness of its bill. (Isla San Andrés, Colombia; October 15, 2014.) © Félix Uribe

“San Andrés Mockingbird”, M. g. magnirostris—in this view, showing proportions similar to other subspecies of Tropical Mockingbird. (La Laguna, Isla San Andrés, Colombia; November 2, 2017.) © Anthony Levesque

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of ten recognized subspecies, one of which was formerly classified as a separate species, the “San Andrés Mockingbird” (magnirostris).

See below for comparisons of Tropical Mockingbird with Northern and Chalk-browed Mockingbirds.

Cf. Northern Mockingbird. Northern and Tropical Mockingbirds overlap regularly across much of southern Mexico in Veracruz, Oaxaca, and Chiapas, and likely also in the Yucatán Peninsula and northern Central America—where recent records indicate that Northern probably occurs regularly but has been overlooked due to its similarity to Tropical. Occasional overlap is also possible in the West Indies, as their ranges approach one another in the Leeward Islands. Two U.S. records of Tropical Mockingbird in the 2010s suggest additional potential for overlap due to ship-assisted vagrancy.

Their vocalizations are essentially identical, so by sound alone a person who is familiar with either species would readily confuse them. In areas where both gray mockingbirds may occur, a clear look at the spread wing is necessary and sufficient for positive identification. Northern has large white wing-patches that flash conspicuously in flight, whereas Tropical has mostly dark wings that do not show white patches in flight.

Northern Mockingbird, taking flight, showing diagnostic white wing patches and white outer tail feathers. (Boul de l’Énergie, Beauharnois, Quebec; July 23, 2019.) © Lucien Lemay

Tropical Mockingbirds in combat, showing white-cornered tail and dark, unmarked wings. (San Pablo Hummingbird Retreat, Sangre Grande, Trinidad; May 9, 2019.) © Jason Fidorra

The tails also differ consistently, but less obviously than the wings. Northern’s two outer feathers are essentially all-white, so it shows broad white sides when spread. Tropical’s tail feathers are broadly tipped with white, more so on the outer feathers, so it appears white-cornered when spread.

Northern Mockingbird, with tail folded and appearing mostly black with a narrow white outer edge—not conclusively identifiable in this photo. (Franklin Mountains State Park, Texas; February 2, 2019.) © Juan Miguel Artigas Azas

Tropical Mockingbird, showing some white on the wings and narrow white outer edge on the tail—not conclusively identifiable in this photo. (Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo, Mexico; February 11, 2018.) © Joel Trick

Except for their wings and tails, adults of the two species can appear very similar. Northern tends to appear more neutral gray overall, whereas Tropical tends to show stronger contrast, with blacker wings and whiter underparts. But Tropical is more variable, with some populations or individuals that show richer shades of blue-gray and others that are paler or browner, and some that tend to show more or less pronounced eyebrows, eyestripes, wingbars, and streaks on the flanks.

Cf. Chalk-browed Mockingbird. Tropical and Chalk-browed Mockingbirds overlap widely in Brazil. Chalk-browed generally has a wider, more prominent eyebrow—for which it is named—but Tropical’s eyebrow varies so this feature alone is unreliable.

The most consistently observable distinction is the upperparts. Typically, Tropical is gray and unmarked, whereas Chalk-browed is brown and streaked—including the crown.

Additional Photos of Tropical Mockingbird

Tropical Mockingbird. (Grand Palladium Colonial Resort, Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, Mexico; November 28, 2021.) © Yves Darveau

Tropical Mockingbird, showing white terminal band on folded tail. (Mayan Palace Riviera Maya, Playa Paraiso, Quintana Roo, Mexico; February 3, 2018.) © Christopher Merke

Tropical Mockingbird. (Las Cruces, Petén, Guatemala; September 19, 2018.) © Carlos Echeverría

Tropical Mockingbird with almost pure-black wings. (San José, Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico; July 15, 2017.) © Amy McAndrews

Tropical Mockingbird, showing typically pale-gray upperparts with blackish wings and tail. (San Gervasio, Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico; February 4, 2014.) © Tim Avery

Tropical Mockingbird, taking flight, showing dark, unmarked wings. (Xelhá, Quintana Roo, Mexico; April 21, 2008.) © Tom Murray

Tropical Mockingbird, juvenile. (La Sabana Metropolitan Park, San José, Costa Rica; May 15, 2019.) © Daniel Martínez

Tropical Mockingbird—apparently an immature molting into adult plumage, resembling a grackle. (Christoffel National Park, Curaçao; September 20, 2014.) © Piet Grasmaijer

References

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2020. Mimus gilvus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22711029A139345947. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22711029A139345947.en. (Accessed December 27, 2021.)

Brewer, D., and B.K. MacKay. 2001. Wrens, Dippers, and Thrashers. Yale University Press.

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed December 27, 2021.)

Fagan, J., and O. Komar. 2016. Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garrigues, R., and R. Dean. 2014. The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (Second Edition). Cornell University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and G. Tudor. 1989. The Birds of South America, Volume I: The Oscine Passerines. University of Texas Press.

Stiles, F.G., A.F. Skutch, and D. Gardner. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2021. Sabiá-da-praia, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/sabia-da-praia. (Accessed December 27, 2021.)

Xeno-Canto. 2021. Northern Mockingbird – Mimus gilvus. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Mimus-gilvus. (Accessed December 27, 2021.)