Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common to abundant and conspicuous across substantial portions of the Americas, Africa, western Europe, and the Middle East. Especially abundant in tropical and subtropical lowlands of the Americas, including the plains along the Gulf of Mexico from Texas to Florida, and generally throughout much of Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, and South America.

Western Cattle Egret

Bubulcus ibis

Family: Ardeidae

Africa, Europe, southwestern Asia, and the Americas.

Approximate distribution of the Western Cattle Egret. © Xeno-Canto 2022

Often associated with grazing livestock, but also occurs in other open terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Its range has expanded due to the large-scale development of open agricultural and urban spaces. Mostly resident overall, but local populations—most noticeably at the margins of its range—are partly migratory, nomadic, or dispersive.

Widespread in Africa except for its most barren deserts and densest forests. Also resident on most of the surrounding island groups: the Canaries, Cape Verde, São Tomé, Príncipe, Bioko, Socotra, Madagascar, the Comoros, and the Seychelles.

Western Cattle Egret on Bermuda, where it is a frequent vagrant. (November 3, 2021.) © Miguel Mejias

European range has expanded dramatically during the 1900s and 2000s. In the early 1900s it was localized in the southern Iberian Peninsula, and began spreading north and east, breeding in southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981, Italy in 1985, and England in 2008. As of 2022, it is resident throughout the most of western Europe from central England and the Netherlands south through the Iberian Peninsula and Italy, and on all large islands of the western Mediterranean, east to Sicily.

Its colonization of southeastern Europe appears to be proceeding more gradually. There are substantial populations in Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus, and a few localized outpost populations scattered north to Hungary and southeastern Romania.

Wanderers regularly stray deeper into central Europe, including all parts of Germany and Czechia, and southern Poland, and north to southern Scandinavia (to southern Finland). More exceptionally recorded north to Iceland, northern Norway, and central Finland.

Farther east, a local resident across the Trancaucasus to the Caspian lowlands of Iran, and south through the Middle East, in pockets of suitable habitat, to Yemen, Oman, and southern Iran (east to the Straits of Hormuz). Wanderers regularly stray north and east to southern Ukraine, the North Caucasus (to Kalmykia), Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

Breeding Bird Survey Abundance Map: Western Cattle Egret. U.S. Geological Survey 2015

The Western Cattle Egret’s colonization of the New World began sometime around 1877, when a flock was observed in Surinam. It spread rapidly north and west across northern South America, the West Indies, and Central America. The first North American colonists appeared in Florida around 1941, where breeding was first confirmed in 1953.

As of 2022, it is well-established throughout the West Indies, Middle America and southern North America north to northern California, North Dakota, the southern Great Lakes, and New Jersey. Regularly occurs in small numbers essentially throughout the rest of the contiguous U.S. and southern Canada, including Newfoundland. Exceptional vagrants have been recorded north to south-coastal Alaska, southern Northwest Territories (Fort Simpson), Lake Athabasca, and James Bay.

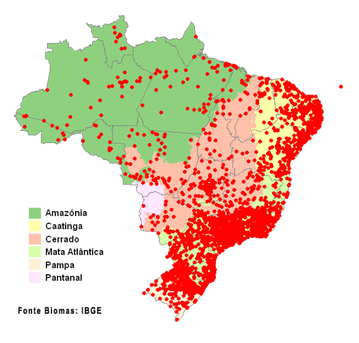

Brazilian records by municipality. © WikiAves 2022

Expansion southward in the Americas began more slowly but proceeded more rapidly. The first documented Brazilian record was in 1964 on the Ilha de Marajó, and the large-scale spread from the Caribbean lowlands south along the Pacific coast and into the Andes also began around the late 1950s and early ‘60s. By the 2000s, it was already either resident or a regular visitor throughout South America, wherever suitable habitat exists, up to 4,400 m elevation in the Andes, south to Tierra del Fuego, and west to the Galápagos.

Introduced to the Hawaiian Islands in 1959 to help control insect pests in livestock. Small flocks totaling 105 individuals were released at seven sites: two on Oahu, two on the Big Island, and one each on Kauai, Molokai, and Maui. It has increased to become one of Hawaii’s predominant bird species, present throughout the main islands and a frequent vagrant to the Northwest Chain.

Wanderers regularly appear on many distant offshore islands, including Bermuda, the Azores, Madeira, Fernando de Noronha, Ascension, St. Helena, Tristan da Cunha, the Falklands, South Georgia, Socorro, Cocos, Juan Fernández, Réunion, and Mauritius. It has colonized Midway Atoll on multiple occasions, but as an invasive species that predates native seabird nests, it has been subject to eradication efforts.

Identification

A small, compact, mostly terrestrial, white heron with a stout, orange or yellow, daggerlike bill. Strongly associated with large, grazing mammals, including cattle, which it often accompanies and sometimes rides. It specializes in capturing grasshoppers and other prey disturbed by mammalian companions.

Extremely similar to the closely related Eastern Cattle Egret. Eastern averages slightly larger and proportionately longer-billed than Western, but they are reliably distinguished only by differences in breeding plumage.

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage, holding an anole. (Fulshear, Texas; July 6, 2020.) © Jamie B. Wagner

In breeding plumage, the otherwise plain-white plumage is augmented by shaggy, buffy-orange feathers on the crown, nape, and chest, and long, wispy, buffy-orange ornamental plumes on the back. Eastern’s breeding plumage differs in having more extensive buffy-orange plumage throughout the face and neck. Eastern also tends to attain richer shades of orange than Western—although the coloration of both varies seasonally and individually.

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage, displaying. (San Diego Zoo Safari Park, San Diego, California; April 9, 2021.) © Alison Davies

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage. (Whites Ranch Road, Chambers County, Texas; May 14, 2020.) © Brandon Nidiffer

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage with full flush coloration of the bill and facial skin. (Wellton, Arizona; May 9, 2020.) © Mary McSparen

In peak breeding flush, the bill and facial skin are multicolored: yellow-orange toward the tip, becoming red toward the base, then shading to purple on the lores, with orange or red eyes.

Nonbreeding plumages are all-white. The bill is yellowish.

Western Cattle Egret in nonbreeding plumage. (Maumee Bay State Park, Ohio; November 4, 2019.) © Darlene Friedman

In all plumages, the legs vary from orange to purplish to gray to black. Breeding adults often show orange or purplish legs, and nonbreeding birds more typically have black legs.

In flight, holds its head far back, creating a bulging, rounded keel when viewed in silhouette.

Western Cattle Egret in nonbreeding plumage. (Hammonasset Beach State Park, Connecticut; November 13, 2021.) © Jeremy Cohen

Notes

Monotypic species. Traditionally considered conspecific with the Eastern Cattle Egret (coromandus), known collectively as the Cattle Egret (ibis).

The status of these forms as either separate species or distinctive subspecies is debatable, but the trend since the early 2000s has been toward recognition as two species. They are highly mobile and have been observed to overlap regularly (on the Arabian Peninsula), yet their populations apparently remain distinct—readily detectable only in breeding plumage. Genetic markers reportedly indicate substantial, long-term divergence of their populations, which would be unlikely in this scenario unless they effectively distinguish between themselves as different.

See below for a comparison of the Western and Eastern Cattle Egrets with the Intermediate Egret.

Cf. Intermediate Egret. Western and Eastern Cattle Egrets overlap with the three forms of Intermediate Egret across most of Africa, southern and eastern Asia, and Australasia. Cattle Egrets are far more likely to be found in dry habitats, but both are found in aquatic habitats—especially in open marshes and rice fields. In their nonbreeding plumages, all have pale yellowish bills of approximately the same length, pale eyes, all-white plumage, and somewhat variable, usually blackish legs. The differences between them are subtle and mostly unreliable for identification.

Cattle Egrets are shorter and thicker, and tend to appear hunched, whereas Intermediate Egrets usually appear proportionately long, thin, and stretched. The Intermediate Egret’s head appears smaller in relation to its bill. With familiarity, such structural differences are often sufficient for quick field identification. However, in some postures the two can convey roughly the same impression.

Nonbreeding Intermediate Egrets often have a dark tip on an otherwise pale bill, which can be useful indicator as it is not typical of Cattle Egrets (they sometimes have a dark tip, but much less often).

More Images of the Western Cattle Egret

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage. (Princess Anne Wildlife Management Area, Virginia Beach, Virginia; April 17, 2018.) © Mary Catherine Miguez

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage. (Natchitoches, Louisiana; May 22, 2019.) © Charles Lyon

Western Cattle Egret entering breeding plumage. (Ohiki Road, Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, Kauai, Hawaii; January 1, 2019.) © Jim Merritt

Western Cattle Egret in breeding plumage. (Bono, Ohio; September 5, 2020.) © Andrew Simon

References

Ahmed, R. 2011. Subspecific identification and status of Cattle Egret. Dutch Birding 33:294-304.

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2019. Bubulcus ibis (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22697109A155477521. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22697109A155477521.en. (Accessed March 14, 2022.)

Borrow, N., and R. Demey. 2004. Birds of Western Africa. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed March 17, 2022.)

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Heinzel, H., and B. Hall. 2000. Galápagos Diary: A Complete Guide to the Archipelago’s Birdlife. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Martínez Piña, D.E., and G.E. González Cifuentes. 2021. Field Guide to the Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Porter, R.F., S. Christensen, and P. Schiermacker-Hansen. 1996. Field Guide to the Birds of the Middle East. T & A D Poyser, London.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press.

Redman, R., T. Stevenson, T., and J. Fanshawe. 2009. Birds of the Horn of Africa: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Socotra. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Sinclair, I., and P. Ryan. 2003. Birds of Africa South of the Sahara. Princeton University Press.

Sinclair, I., P. Hockey, W. Tarboton, and P. Ryan. 2011. Birds of Southern Africa (Fourth Edition). Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd. Cape Town, South Africa.

Svensson, L., K. Mullarney, and D. Zetterström. 2009. Birds of Europe (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2022. Garça-vaqueira, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/garca-vaqueira. (Accessed March 17, 2022.)

Xeno-Canto. 2022. Western Cattle Egret – Bubulcus ibis. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Bubulcus-ibis. (Accessed March 17, 2022.)