Birdfinding.info ⇒ Increasingly widespread and common in many parts of Europe. The largest concentrations occur in Spain and France from October to early March. In central Europe, the prime location is Hungary’s Hortobágy National Park, a favored migration stopover site where smaller numbers breed and winter. In China, the largest flock winters at Poyang Lake, among other cranes.

Common Crane

Grus grus

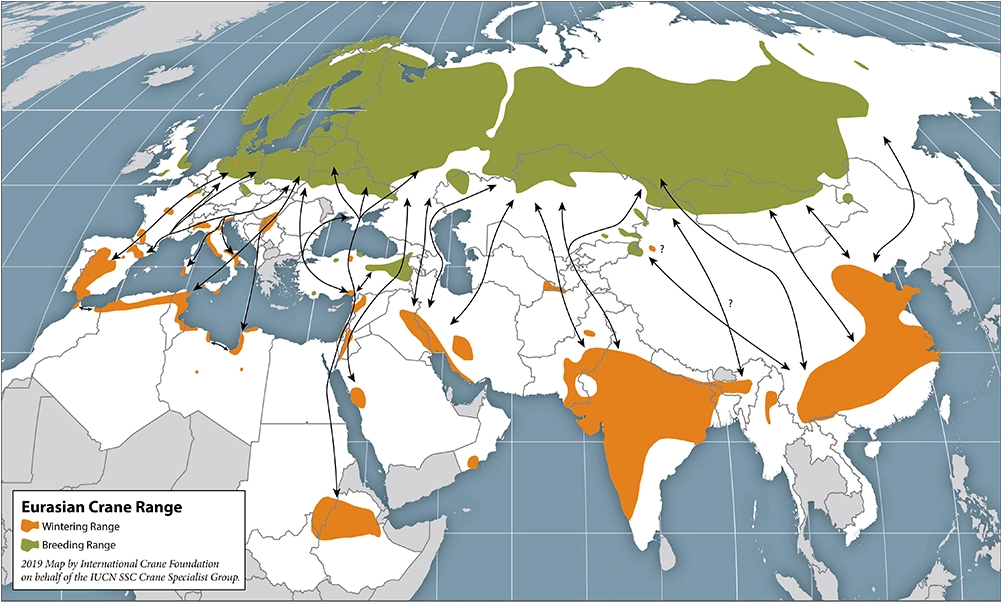

Breeds in northern Eurasia; winters in southern Eurasia and northern Africa.

Approximate distribution of the Common Crane. © International Crane Foundation 2019

Breeding. Nests in bogs and marshlands across a wide swath of northern Eurasia. In Europe, it breeds nearly throughout Scandinavia, Poland, and the Baltics, south to southern England, the Netherlands, northeastern France, northern Germany, Czechia, Hungary, and northern Ukraine, east across taiga belt and steppes of Russia, northern Kazakhstan, and Mongolia to northeastern China and the Kolyma River in Siberia.

The European breeding range has been expanding since the 1990s, with small populations recently established and growing in England, the Netherlands, France, and Hungary, reoccupying historical breeding grounds. In 2019, the total population west of the Ural Mountains was estimated at ~590,000 birds, steadily increasing. The total population east of the Urals was estimated at ~112,000, but decreasing.

The Common Crane (immature shown) returned to England as a breeding species in the 2000s, decades after it had been extirpated. (Wark, Northumberland, England; February 23, 2019.) © Paul Chapman

Two small southerly-breeding populations are sometimes recognized as separate subspecies. The “Transcaucasian Common Crane” breeds on plateaus and intermontane valleys of central and eastern Turkey, southern Georgia, Armenia, and Iran (near extirpation). The “Tibetan Common Crane” breeds in southeastern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and western Xinjiang. Both are endangered and generally decreasing, with 2019 estimates of 250-300 “Transcaucasian” and ~1,000 “Tibetan”.

Nonbreeding. Winters mainly on fertile plains with extensive wetlands. The winter range extend the full breadth of the Old World from western Europe and northwestern Africa to eastern China.

The European wintering range was historically concentrated in the central Iberian Peninsula and locally in France and Italy, but has expanded nearly throughout the continent north to southern England, Denmark, southern Sweden, and Lithuania, south to the major islands of the western Mediterranean, and east to southern Romania, Bulgaria, and northern Greece. The vast majority—more than half of the global population—winters in Spain (~266,000 estimated in 2014) and France (~160,000 estimated in 2015), with substantial flocks also in Germany (~20,000), Hungary (~20,000), Italy, and Portugal (~8,000), and smaller flocks elsewhere.

Over one-third of the global population of Common Cranes winters on the Spanish plains. (Fuente de Piedra, Málaga, Andalucía, Spain; November 21, 2018.) © Santiago Caballero Carrera

In northwestern Africa, small and decreasing numbers winter in scattered areas between southwestern Morocco and northeastern Libya. In East Africa, a substantial subpopulation winters in northern and central Ethiopia.

In the Middle East, winters mainly near the eastern Mediterranean coast from southern Turkey to Israel—the majority in this region winters in Israel (~50,000). Smaller flocks also winter locally in northern and central Turkey. Much smaller and decreasing numbers winter in eastern Iraq and and western Iran, and at scattered sites along the Red Sea and southern Oman.

In South Asia, the largest portion (~70,000) winters in Gujarat Province, western India. Smaller numbers winter in adjacent lowlands of Pakistan, locally across central and northern India east to Arunachal Pradesh, and south into the central lowlands of Myanmar. Starting in the 1990s, substantial numbers have remained to winter in central Asia: ~30,000 in the Amu Darya River Valley on the borders of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, and ~1,500 in the Tejen River Valley of southern Turkmenistan.

In East Asia, ~12,000 winter locally in a few areas scattered across central and eastern China north to Beijing and south to northern Hunan, Jiangxi, and Shanghai. Very small numbers winter farther east, among other cranes in South Korea and southern Japan (Kyushu).

The Common Crane is a rare but increasingly regular vagrant to North America. (Bow, Washington; April 28, 2021.) © Kenneth Trease

Movements. Well over half of the global population migrates through western Europe along a broad front from the Iberian Peninsula to Scandinavia. Three smaller, but substantial subpopulations migrate through central Europe (most funneling through eastern Hungary), eastern Europe (from Ethiopia through Israel, then either across or east of the Black Sea), west-central Asia (between Gujarat and western Siberia).

The northbound migration begins in late February or early March, and large flocks accumulate at favored mid-route stopover sites in late March and early April, before continuing to their main breeding areas.

The southbound migration is more protracted, with departures from high arctic breeding grounds beginning in mid-August and last arrivals on wintering grounds in December.

Occasional but apparently increasing as a vagrant to Iceland and Macaronesia, where it has been recorded on the Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands.

Also apparently increasing as a vagrant to North America, where it has been recorded in migratory flocks of Sandhill Cranes in many parts of the continent: from Alaska to Quebec and south to several western and midwestern states, from California to Indiana. Many records refer to particular individuals that are detected in multiple locations during migration and return to the same sites in successive years.

Identification

A gray crane with a predominantly black head and neck, a broad white stripe that extends back from the eye down the nape, and a small red patch on the crown.

Common Crane. (Slano Kopovo, Vojvodina, Serbia; March 7, 2022.) © Василий Калиниченко

The red crown patch is bare or nearly bare skin. The bill is horn-colored, and the legs are blackish.

Common Crane, facial close-up showing small central crown-patch of bare red skin. (Lake Agamon, Israel; December 6, 2021.) © דויד סבן

The plumage is almost entirely gray, but often stained rusty or brownish on the back as a result of preening with soil—apparently used as camouflage during the nesting season.

When seen in flight, the spread wings show black flight feathers that contrast with pale-gray coverts.

Common Crane in flight, dorsal view showing isolated gray wedge or notch on the leading edge of the primary coverts. (Hornborgasjön, Sweden; April 3, 2021.) © Jan Andersson

Common Crane in flight, ventral view. (Hrabanovská Černava Nature Reserve, Středočeský Kraj, Czechia; February 19, 2022.) © Michala Sůvová

The upperside of the spread wing has peculiar details in the pattern: beyond the wrist the coverts are mostly black with a small, isolated gray wedge or notch on the leading edge of the primary coverts.

Common Crane, juvenile. (Groß Mohrdorf, Germany; October 6, 2011.) © Holger Teichmann

Juveniles are mostly gray with a cinnamon tinge that is most pronounced on the head, less so on the neck and back. The juvenile’s bill is orangish.

On older immatures, the cinnamon tinge disappears from the neck and back, and is more incrementally replaced by black and white on the head. The last noticeable change is the loss of feathers on the crown, leaving bare red skin exposed.

Common Crane, immature, facial close-up showing transition to adult coloration, but still lacking bare red central corwn-patch. (Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, U.A.E.; January 16, 2020.) © Peter Arras

Notes

Usually regarded as a monotypic species, but some researchers (e.g., Prange and Ilyashenko 2019) have proposed up to four subspecies: the “Western” (grus); “Eastern” (lilfordi); “Transcaucasian” (archibaldi); and “Tibetan” (korelovi).

See below for a comparison of the Common Crane with the Demoiselle Crane.

Cf. Demoiselle Crane. Common and Demoiselle Cranes occur together over large expanses of Eurasia and northern Africa. They are unlikely to be confused if seen at rest, but in flight they can be difficult to distinguish. Their overall coloration and patterns in flight are nearly identical when viewed at long range. If the coloration is seen clearly from below, the extent of black on the neck differs significantly—on Common it is confined to the neck, whereas on Demoiselle it extends down past the chest.

Common Crane, above, with Demoiselle Crane, showing near identical appearance when viewed in flight at long range. (Tranitsa, Shumen, Bulgaria; April 23, 2011.) © Daniel Mitev

Demoiselle Crane, showing black extending down the breast. (Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; February 10, 2010.) © Garima Bhatia

More Images of the Common Crane

Common Crane in flight, dorsal view. (Maña, Nitriansky Kraj, Slovakia; May 26, 2022.) © Radovan Václav

Common Crane, juvenile in flight, apparently a representative of the endangered “Transcaucasus” population or subspecies (proposed as G. g. archibaldi). (Eksisu Grass, Erzincan, Turkey; August 21, 2019.) © Michael Bokämper

References

BirdLife International. 2016. Grus grus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22692146A86219168. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22692146A86219168.en. (Accessed November 22, 2022.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed November 22, 2022.)

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2018. Birds of the Canary Islands. Christopher Helm, London.

Prange, H., and E.I. Ilyashenko. 2019. IUCN SSC Crane Specialist Group – Crane Conservation Strategy, Species Review: Eurasian Crane (Grus grus). In Crane Conservation Strategy (C.M. Mirande, and J.T. Harris, eds.), 397-423. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Hollom, P.A.D., R.F. Porter, S. Christensen, and I. Willis. 1988. Birds of the Middle East and North Africa. T & AD Poyser, Calton, England.

Howell, S.N.G., I. Lewington, and W. Russell. 2014. Rare Birds of North America. Princeton University Press.

Hughes, J.M. 2008. Cranes: A Natural History of a Bird in Crisis. Firefly Books, Richmond Hill, Ontario.

International Crane Foundation. 2022. Species Field Guide: Eurasian Crane. https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/eurasian-crane/. (Accessed November 22, 2022.)

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Redman, R., T. Stevenson, T., and J. Fanshawe. 2009. Birds of the Horn of Africa: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Socotra. Princeton University Press.

Xeno-Canto. 2022. Common Crane – Grus grus. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Grus-grus. (Accessed November 22, 2022.)