Birdfinding.info ⇒ Reportedly named by Marie Antoinnette—who was charmed by the elegance of a captive pair brought to her in Paris and likened them to young ladies of high society—the Demoiselle Crane is numerous and widespread, but decreasing and disappearing from some parts of its range. It remains common in summer on the steppes of Central Asia. In winter, large flocks can be found in Rajasthan and Gujarat, and seen especially well at Khichan (feeding station in the village) and the Tal Chhapar Sanctuary. In Europe it is very scarce, but can sometimes be found on migration in Cyprus—especially at Akrotiri in late March, early April, late August, and September.

Demoiselle Crane

Anthropoides virgo

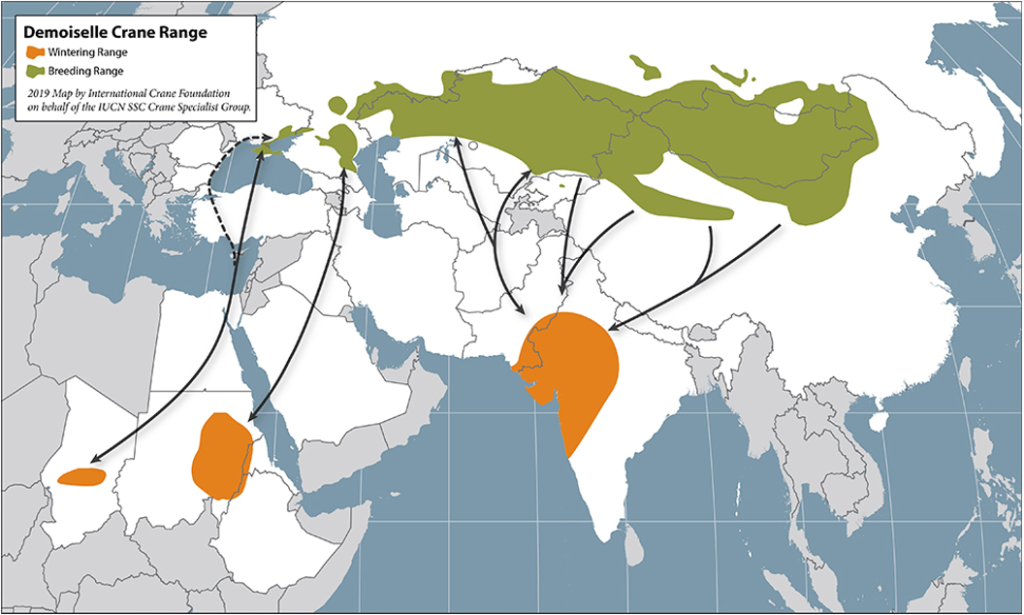

Breeds on steppes of Eurasia. Winters on dry plains of the Sahel and South Asia.

Approximate distribution of the Demoiselle Crane. © Xeno-Canto 2022

Breeding. Breeds on open plains and high plateaus—up to ~5,000 m elevation—usually within relatively close proximity to water: rivers, lakes, ponds, marshes, or irrigation canals. The climatic variability of the steppe region dictates a somewhat nomadic lifestyle, responding to the changing availability of water from year to year. In wet years, it may nest anywhere on the steppes, including deserts, as long as water is present nearby. In dry years, it shifts toward more heavily vegetated areas where water sources are more reliable.

The global population can be understood as three regional subpopulations: European; Central Asian; and East Asian. Each of these consists of four distinct breeding “flocks” (loosely speaking) or statistically convenient groupings.

Demoiselle Crane on its barren Mongolian breeding grounds. (Gun Galuut Nature Reserve, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; May 8, 2021.) © Jugdernamjil Nergui

The European subpopulation (~45,000-58,000) breeds from southern Ukraine to western Kazakhstan: (1) an estimated 540-600 individuals along the northern Black Sea and Sea of Azov coasts from the Dnipro River mouth east through Crimea to the Taman Peninsula and southwestern Rostov Oblast; (2) ~200-300 along the Middle Don River in eastern Rostov and southwestern Volgograd Oblasts; (3) ~30,000-40,000 on the plains west of the northern Caspian Sea in Dagestan, Kalmykia, Astrakhan, Stavropol, and southern Rostov Oblast; and (4) ~15,000-17,000 on the plains north of the Caspian Sea from the Volga River northeast to Samara Oblast in Russia and southeast to Atyrau in Kazakhstan.

The Central Asian subpopulation (~57,000-67,000) breeds from central Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan: (1) ~2,500-3,000 south of the Ural Mountains in Orenburg, Chelyabinsk, and Kurgan Oblasts; (2) ~4,000 in Russia’s Altai Republic; (3) ~50,000-60,000 across most of Kazakhstan; and (4) ~20-40 isolated in foothills of central Kyrgyzstan.

The East Asian subpopulation (~65,000-98,000) breeds from south-central Siberia to northeastern China: (1) ~3,000 in Krasnoyarsk and Khakassia; (2) ~12,000-15,000 in Baikal and Transbaikalia; (3) ~40,000-70,000 across most of Mongolia; and (4) ~10,000 in adjacent provinces of northern China: mainly in Inner Mongolia and northern Xinjiang; marginally in Qinghai, Heilongjiang, and Jilin.

Also bred historically on the Iberian Peninsula, north-central Morocco, and eastern Turkey, but those populations were last reported in 1924, 1984, and 2004, respectively.

Dense flock of an estimated ~7,000 Demoiselle Cranes at the famous feeding station in the village of Khichan. (Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; February 18, 2019.) © John Gregory

Nonbreeding. Winters on open plains, including grasslands, agricultural fields, and deserts, usually in association with water bodies. Typically feeds on dry ground and gathers to roost overnight on small islands, mudflats, or marshes.

The small Ukrainian breeding population winters mainly in Chad. The breeding populations of southwestern Russia and western Kazakhstan winter mainly in Sudan and adjacent parts of Eritrea and Ethiopia. On at least one occasion (1985-86) a small flock wintered in coastal Kenya.

Central and East Asian populations winter mainly in western India and adjacent Pakistan. Small numbers winter at scattered sites in central and southern India.

Movements. Northbound migration begins in early March, when the westernmost subpopulation departs from Chad. These birds generally follow the Nile Valley, then fly across the eastern Mediterranean or along its eastern coastline, through central Turkey and across the Black Sea to Crimea.

The flocks that winter in Sudan evidently fly directly over the Red Sea, stop briefly in western Saudi Arabia, then fly directly over the northern Arabian Desert and Iraq to the Aras River Valley in Azerbaijan and Lake Urmia in Iran before dispersing to the western steppes.

Approximate distribution of the Demoiselle Crane, showing partly circular migration routes in Asia. © International Crane Foundation 2019

The much larger flocks that winter in India migrate north through Pakistan, then slightly northwest across northeastern Afghanistan and into eastern Uzbekistan, then fan out across the vast expanses of Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and southern Siberia. Very few depart India directly over the Himalayas en route to Mongolia.

Southbound migration begins in mid-August. The western subpopulations largely retrace their springtime routes, with many congregating around Lake Manych-Gudilo in Kalmykia before heading south across the Caucasus, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.

Demoiselle Cranes occasionally overshoot their breeding grounds and reach Scandinavia. (Västmanlands Län, Sweden; June 13, 2014.) © Lars Petersson

Unlike their spring migration, most Central Asian breeders take relatively direct routes southbound, flying directly over the Himalayas. Flocks congregate at Torey Lakes in Transbaikalia, numerous sites in northern Kazakhstan and Mongolia, Bali Kun Lake in Xinjiang, and Qinghai Lake in Qinghai, before flying more or less nonstop over the Himalayas to western India.

Somewhat regular as a vagrant in East Asia, with records from several provinces of eastern China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan.

Spring overshots are occasionally reported from eastern Europe and Scandinavia. There are several isolated fall records from the full breadth of Europe—some are of known escapees, some are presumably wild vagrants.

In North America, an individual spent the winter of 2001-02 at Woodbridge Ecological Reserve in central California, then was seen on northbound migration in Smithers, B.C., and Gustavus, Alaska. This bird was widely regarded as a natural vagrant, but not accepted as such by the records committees.

Identification

An elegant gray crane with a predominantly black head, neck, and breast, and long white facial plumes that extend back from the eye down the nape. The smallest of all cranes, but still a large bird, and possible to mistake for other crane species when seen at long range.

Demoiselle Crane. (Chuya Steppe, Altai Republic, Russia; June 9, 2018.) © Pavel Parkhaev

The black feathers on the breast are elongated. The gray tertials are also elongated and extend far past the tip of the tail.

The eyes are a vivid blood-red; the bill has a horn-colored or slightly greenish base and a variably reddish tip.

Demoiselle Crane, facial close-up showing blood-red eye and reddish-tipped bill, in flock at feeding station. (Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; December 29, 2016.) © Ritvik Singh

When seen in flight, the spread wings show black flight feathers that contrast with pale-gray coverts. Seen from below, the black of the neck extends far down the chest.

Demoiselle Crane in flight, ventral view showing black extending down the chest. (Vijaysagar Lake, Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; December 26, 2016.) © Oscar Campbell

Demoiselle Crane in flight, dorsal view showing small gray wedge on the leading edge of the primary coverts. (Tal Chhapar Sanctuary, Churu, Rajasthan, India; January 12, 2016.) © Lars Petersson

As on the Common Crane, the upperside of the wing typically shows an isolated pale-gray wedge or notch on the leading edge of the otherwise-black primary coverts (but this pattern is usually stronger on the Common Crane).

Immatures resemble adults overall, but often have an all- or mostly-gray head, lacking the long white facial plumes.

Demoiselle Crane, immature with all-gray head. (Hulimangala, Bangaluru, Karnataka, India; December 24, 2015.) © Albin Jacob

Demoiselle Crane, immature with mostly dark head. (Budgam, Jammu & Kashmir, India; October 10, 2021.) © Sheikh Riyaz

Cf. Common Crane. Common and Demoiselle Cranes occur together over large expanses of Eurasia and northern Africa. They are unlikely to be confused if seen at rest, but in flight they can be difficult to distinguish. Their overall coloration and patterns in flight are nearly identical when viewed at long range. If the coloration is seen clearly from below, the extent of black on the neck differs significantly—on Common it is confined to the neck, whereas on Demoiselle it extends down past the chest.

Common Crane, above, with Demoiselle Crane, showing near identical appearance when viewed in flight at long range. (Tranitsa, Shumen, Bulgaria; April 23, 2011.) © Daniel Mitev

Common Crane in flight, ventral view showing all-gray breast, with black limited to the neck. (Hrabanovská Černava Nature Reserve, Středočeský Kraj, Czechia; February 19, 2022.) © Michala Sůvová

More Images of the Demoiselle Crane

Demoiselle Crane. (Vijaysagar Lake, Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; February 17, 2015.) © Rofikul Islam

Demoiselle Crane. (Vijaysagar Lake, Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; February 2, 2018.) © Amarendra Konda

Demoiselle Crane flock at feeding station. (Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; March 2, 2018.) © Justin Peter

Demoiselle Crane flock at feeding station. (Khichan, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India; February 18, 2019.) © John Gregory

References

BirdLife International. 2018. Anthropoides virgo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22692081A131927771. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22692081A131927771.en. (Accessed November 30, 2022.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed November 30, 2022.)

Ilyashenko, E.I. 2019. IUCN SSC Crane Specialist Group – Crane Conservation Strategy, Species Review: Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo). In Crane Conservation Strategy (C.M. Mirande, and J.T. Harris, eds.), 383-396. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Howell, S.N.G., I. Lewington, and W. Russell. 2014. Rare Birds of North America. Princeton University Press.

Hughes, J.M. 2008. Cranes: A Natural History of a Bird in Crisis. Firefly Books, Richmond Hill, Ontario.

International Crane Foundation. 2022. Species Field Guide: Demoiselle Crane. https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/demoiselle-crane/. (Accessed November 30, 2022.)

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Xeno-Canto. 2022. Demoiselle Crane – Grus virgo. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Grus-virgo. (Accessed November 30, 2022.)