Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common in its core winter and migratory range along the coasts, rivers, and lakes of eastern China and South Korea, and on its Mongolian and Daurian breeding grounds in summer. Uncommon as a winter visitor to Hong Kong and Taiwan, and rare but apparently regular as a winter vagrant to Japan and the Gulf of Thailand.

Mongolian Gull

Larus mongolicus

Breeds in east-central Asia; winters along coasts and rivers of eastern Asia.

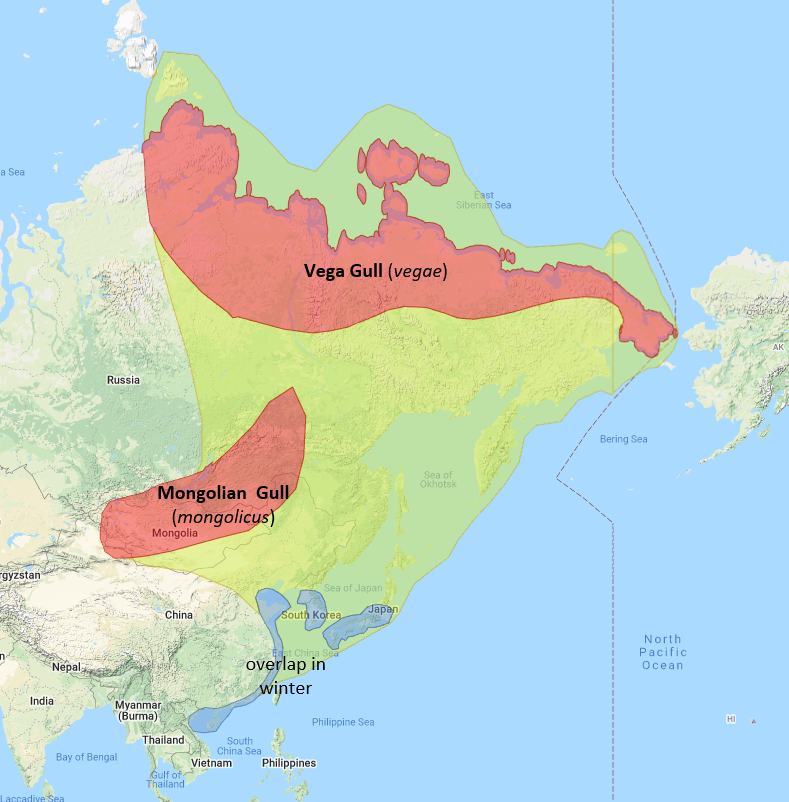

Approximate distributions of Vega and Mongolian Gulls, which are sometimes regarded as conspecific. © Xeno-Canto 2022

Breeding. Nests on islands in lakes of Mongolia and bordering regions of southern Siberia (mainly around Lake Baikal) and northeastern China (mainly around Hulun Lake).

Small, isolated populations breed much farther east along the border of Heilongjiang and Primorskiy Kray (Lake Khanka) and on islands along the Yellow Sea coast of South Korea.

Nonbreeding. Winters mainly along the coasts of the Korean Peninsula and China south to Fujian and Taiwan. A significant portion of the population winters at inland locations in eastern China along rivers and lakeshores, from Hebei south to the Yangtze River Valley in Hunan and Jiangxi. Small numbers winter east to Japan and south to the Gulf of Thailand.

Fall and winter vagrants have been recorded south to the Philippines, and southwest along the coasts of Myanmar and India (west to Goa).

Identification

As a member of the Herring Gull complex, the Mongolian Gull is extremely similar to several closely related forms. Some authorities consider Mongolian to be a separate species, while others consider it conspecific with some combination of: Vega (vegae), American Herring (smithsonianus), and European Herring (argentatus). Mongolian differs subtly, or by tendency, from other Herring-type gulls in wingtip pattern, leg color, immature plumages, molt timing, and other circumstantial factors.

Mongolian Gull in breeding plumage—note dull yellowish leg color. (Ongiin Khiid, Dundgovi, Mongolia; May 25, 2016.) © Frédéric Pelsy

Mongolian Gull in breeding plumage, showing typically extensive black on the wingtip. (Gaivoron, Primorskiy Kray, Russia; May 28, 2019.) © Pavel Parkhaev

Adult Plumages. Adults have a medium-gray mantle, generally paler than Vega, which often occurs with it. The legs vary from pale-pink to yellowish or pale-orange.

The wingtips are extensively black with white “mirrors” near the tips of the outermost one or two primaries. The black portion of the wingtip typically appears triangular with two narrow pale-gray lines projecting into it.

Mongolian Gull, winter adult, showing typically extensive black on the wingtips and limited streaking concentrated on the nape. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 13, 2022.) Anonymous

Mongolian Gull, winter adult, showing red orbital skin and faint streaking mainly on the neck. (Xuanwu Lake Park, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China; August 20, 2005.) © Pavel Parkhaev

Adult Mongolians in winter plumage usually show only limited streaking on the back of the neck.

Mongolian typically enters winter plumage in August and goes back into breeding plumage around February—earlier than Vega.

Mongolian Gull, worn juvenile. (Khar-Us Lake, Hovd, Mongolia; October 6, 2019.) © Silas Olofson

Mongolian Gull, juvenile, showing strong contrast between black tail-band and mostly white rump, uppertail coverts, and the base of the tail. (Olkhon Island, Lake Baikal, Russia; August 18, 2015.) © Vadim Ivushkin

Immature Plumages. Juvenile Mongolians are predominantly whitish or pale-brown with darker spots on the mantle and wing coverts, and mostly blackish flight and tail feathers. The spots usually wear off in September, leaving the plumage of most first-winter and first-summer birds mostly whitish overall with narrow chevrons and anchors on the upperparts.

Mongolian Gull, first-winter, showing mostly whitish plumage with black flight feathers. (Choshi, Chiba, Honshu, Japan; December 24, 2000.) © Yoshiki Watanabe

Mongolian Gull, first-winter, showing strong contrast between black tail-band and mostly white rump, uppertail coverts, and the base of the tail. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; December 6, 2020.) Anonymous

On the spread wing, first-year Mongolians show the typical Herring Gull pattern: blackish primaries, primary coverts, and secondaries, with a distinctly paler “window” on the inner primaries.

The tail of first-year Mongolians has a broad blackish terminal band and contrastingly pale base. On juveniles, the rump, uppertail coverts, and the bases of the tail feathers are mostly pale with fine dark barring. Starting with first-winter plumage, the rump and uppertail coverts appear essentially all-white.

Mongolian Gull, second-winter. (Offshore from Samut Songkhram, Thailand; February 7, 2021.) © Wich’yanan Limparungpatthanakij

Mongolian Gull, second-winter. (Bang Pu Recreation Center, Samut Prakan, Thailand; December 20, 2015.) © Pattaraporn Vangtal

Subadult Plumages. Subadults follow the typical progression of four-year gulls, replacing the mottled brown feathers of the wings and mantle with definitive gray feathers from the second winter molt into the third summer.

Mongolian Gull, second-summer—note yellow legs. (Bang Pu Recreation Center, Samut Prakan, Thailand; April 22, 2017.) © Ben Weil

Mongolian Gull, third-summer. (Ningxia Yuehai National Wetland Park, Yinchuan, Ningxia, China; March 8, 2018.) © Tommy Pedersen

Compared to other Herring-types, subadult Mongolians are generally paler at all stages, with more boldly contrasting flight and tail feathers. In particular, the contrast between the blackish tail band and otherwise white, mostly unmarked rump and coverts is a distinctive feature.

Notes

Monotypic species or form, of unsettled status. Has been classified variously as a separate species or as conspecific either with the Caspian Gull (cachinnans) or with some combination of the European Herring Gull (argentatus), American Herring Gull (smithsonianus), and Vega Gull (vegae), and sometimes other forms.

See below for a comparison of the Mongolian Gull with Vega Gull.

Cf. Vega Gull. Together, the Vega and Mongolian Gulls comprise the East Asian contingent of what was once globally known as the Herring Gull. In recent years, Mongolian (mongolicus) has been classified variously as an independent species or as a subspecies of Caspian (cachinnans), Vega (vegae), Arctic Herring (smithsonianus), or Herring (argentatus) Gull. Most taxonomic authorities still classify Vega and Mongolian as conspecific—but genetic analyses and differing life histories indicate that they are at least distinct forms. Their breeding ranges are widely separated: Mongolian breeds on lakeshores deep in the Asian interior at temperate latitudes, whereas Vega breeds on the tundra of northeastern Siberian. In migration and winter, they overlap widely along East Asian coasts from the Sea of Japan to Taiwan and Hong Kong—although the overlap is limited by habitat preferences, as Mongolian tends to favor lakes and estuaries, whereas Vega is more strictly coastal.

Physical differences between Vega and Mongolian are subtle and variable, depending on life-stage and season. Immatures are more readily identifiable than adults. Many individuals require multiple factors to identify, and some are borderline cases that cannot be confidently assigned to one or the other.

Wingtip Pattern: Adult Mongolian typically has more extensive black on the wingtips, forming an almost-complete triangle with two narrow pale tongues projecting into it. The black on Vega’s wingtips typically appears more like a V, solid on the leading edge and broken on the trailing edge, with a mostly gray area in between, usually with white “moons” or a “string of pearls” between the gray and black. (Note, however, that wingtip patterns are not entirely consistent, as some Mongolians have less extensive black than average, and have approximately the typical Vega pattern, including the string of pearls.)

Mongolian Gull in nonbreeding plumage, showing nearly complete black triangle on the wingtips and typically sparse streaking on the nape. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 18, 2022.) Anonymous

Vega Gull in nonbreeding plumage, showing V-shaped black wingtips with “string of pearls” (white spots between the gray and black in the wingtips), and extensive streaking on the head and neck. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 18, 2022.) Anonymous

Leg Color: Adult Mongolian’s legs vary from yellowish to dull orange to pink. Vega’s legs are more consistently pink—and usually more vivid than Mongolian’s. (Note that there are reports of Vega Gulls with yellowish legs, but such individuals appear to be exceptional and some of the reports may result from confusion among Mongolian, Vega, and “Taimyr” Gulls.)

Mantle Color: Vega’s mantle averages somewhat darker gray than Mongolian’s. There is enough variation within Vega that the tone of gray is an inconsistent feature for identification, but many Vegas stand out as dark, and Mongolians generally do not.

Head and Neck Streaking (Nonbreeding): Adults in winter plumage differ in the usual amount and distribution of dark streaks on the head and neck. Many Vega Gulls show extensive streaking all around the neck—forming a necklace—and often have noticeable streaking on the head. Mongolian typically has a partial collar of streaks on the nape, but usually remains clean white on the head and front of the neck. However, the amount of streaking varies widely in both, so this field mark is suggestive but not reliable.

Molt Timing: Mongolian Gull begins nesting in April, almost two months earlier than Vega, and accordingly enters breeding plumage earlier than Vega. Mongolians typically attain their clean, crisp breeding plumage by February, whereas Vegas molt in March and April.

Vega Gull, juvenile, showing mostly black tail with barring on the rump, uppertail coverts, and base of the outer tail feathers. (Southeast Farallon Island, California; October 7, 2014.) © Dan Maxwell

Mongolian Gull, juvenile, showing black tail-band, white rump and uppertail coverts, and fine barring on the base oof the tail. (Khar-Us Lake, Hovd, Mongolia; October 6, 2019.) © Silas Olofson

Rump and Tail Coverts (Immature): First-year Vega and Mongolian Gulls—from juvenile to first-summer plumages—appear to differ consistently in their rump and tail patterns. First-year Vegas tend to show a wider dark tail-band and more dark barring on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers. First-year Mongolians are mostly white on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers, with sparse, thin barring, and tend to show a narrower but darker tail-band. (Both can be black, but Mongolian’s is consistently blackish, whereas Vega’s varies from pale-brown to blackish.)

More Images of the Mongolian Gull

Mongolian Gull in breeding plumage. (Gaivoron, Primorskiy Kray, Russia; May 28, 2019.) © Pavel Parkhaev

Mongolian Gull, first-winter. (Jiahe River, Yantai, Shandong, China; January 27, 2018.) © Kyle Price

Mongolian Gull, second-winter. (Bang Pu Recreation Center, Samut Prakan, Thailand; December 20, 2015.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Mongolian Gull, third-winter. (Bang Pu Recreation Center, Samut Prakan, Thailand; December 8, 2016.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Mongolian Gull, winter adult. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; February 12, 2022.) Anonymous

Mongolian Gull in breeding plumage. (Olkhon Island, Lake Baikal, Russia; August 18, 2015.) © Vadim Ivushkin

Mongolian Gull, first-winter. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; March 14, 2021.) Anonymous

Mongolian Gull, first-winter. (Offshore from Samut Prakan, Thailand; January 23, 2022.) © Sarawin Kreangpichitchai

Mongolian Gull, second-winter. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; February 12, 2022.) Anonymous

Mongolian Gull, third-winter. (Bang Pu Recreation Center, Samut Prakan, Thailand; January 16, 2017.) © Woraphot Bunkhwamdi

References

BirdLife International. 2019. Larus smithsonianus (amended version of 2018 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T62030590A155596462. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T62030590A155596462.en. (Accessed February 15, 2022.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

Černý, D., and R. Natale. 2021. Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes). bioRχiv preprint: http://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.15.452585v1.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed February 15, 2022.)

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Moores, N. 2011. Taimyr Gull Larus (heuglini) taimyrensis: an Update. BirdsKorea. http://www.birdskorea.org/Birds/Identification/ID_Notes/BK-ID-Taimyr-Gull.shtml.

Olsen, K.M., and H. Larsson. 2003. Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia. Princeton University Press.

van Dijk, K., S. Kharitonov, H. Vonk, and B. Ebbinge. 2011. Taimyr Gulls: evidence for Pacific winter range, with notes on morphology and breeding. Dutch Birding 33:9-21.

Xeno-Canto. 2022. Vega Gull – Larus vegae. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Larus-vegae. (Accessed February 15, 2022.)