Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common and conspicuous in its core winter range along the coasts of northeastern Asia from the Russian Far East to central China and Japan. Uncommon farther south, including Hong Kong and Taiwan, where confusingly similar species greatly outnumber it. In North America, it is fairly common from summer into fall around the Bering Strait, including Gambell and Nome, and uncommon but regular elsewhere around the Bering Sea, including the Pribilofs and Aleutians, and north to Barrow.

Vega Gull

Larus vegae

Breeds in northern Siberia; winters along temperate coasts of eastern Asia.

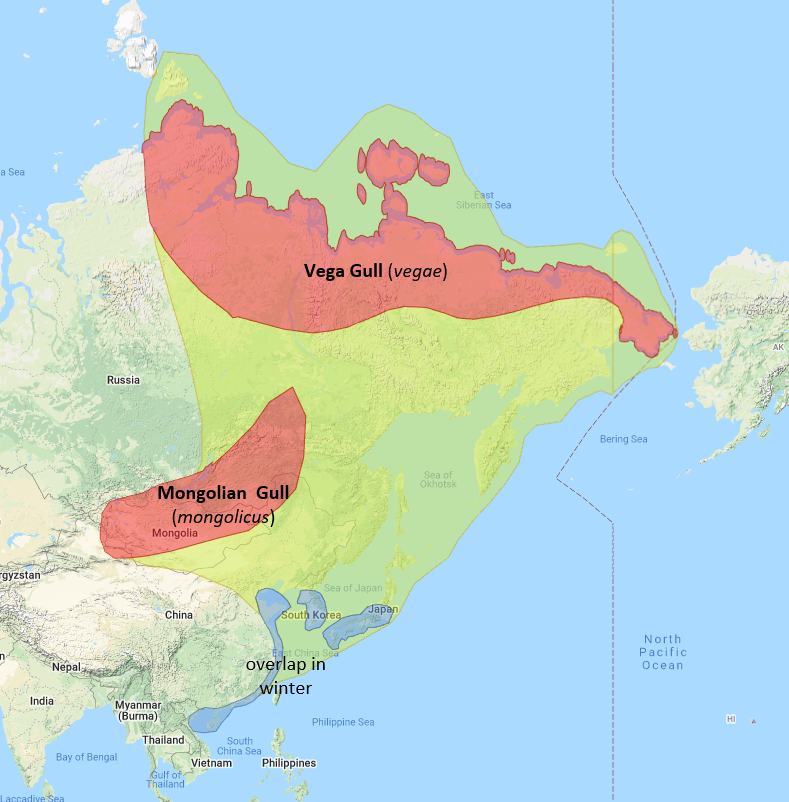

Approximate distributions of Vega and Mongolian Gulls, which are sometimes regarded as conspecific. © Xeno-Canto 2022

Breeding. Nests on Siberian tundra from the Lena River Delta east to the Gulf of Anadyr in Chukotka, and at least occasionally on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska.

Small numbers are generally present in summer and fall elsewhere along Alaska’s northern and western coasts.

Nonbreeding. Winters mainly along coasts from the Sea of Okhotsk and Kamchatka Peninsula south to the Yellow Sea and Japan. Small numbers winter south to Hong Kong and Taiwan, and more exceptionally to Luzon and Hawaii (where most records are from the Northwest Chain).

Fall and winter vagrants have been discovered at various locations in North America: several in California, and isolated individuals in British Columbia, Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, Ontario, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, etc. A few of these have returned to the same location year after year.

Identification

As a member of the Herring Gull complex, the Vega Gull is extremely similar to several closely related forms. Some authorities consider Vega to be a separate species, while others consider it conspecific with some combination of: Mongolian (mongolicus), American Herring (smithsonianus), and European Herring (argentatus). Among these pink-legged Herring Gulls, Vega is generally the darkest. In adult plumage, it usually has a slightly darker gray mantle and often has darker eyes than the others in this group.

Vega Gull, breeding adult. (Nome, Alaska; May 22, 2013.) © Ian Davies

Adult Plumages. Adults have a medium-gray mantle, usually darker than Mongolian and American Herring, but significantly paler than Slaty-backed (schistisagus), which often occurs with it.

Vega Gull, winter adult showing white “string of pearls” between the black and gray in the wingtips. (Brownsville Landfill, Texas; February 21, 2015.) © Willie Sekula

Vega’s wingtips are extensively black with white “mirrors” near the tips of the outermost one or two primaries. The black on Vega’s wingtips typically forms a rough V or U, solid on the leading edge and broken on the trailing edge, with a mostly gray area in between, usually with two or three white “moons” (the so-called “string of pearls”) between the gray and black.

Vega’s irises vary from pale-yellow to olive-brown, and its orbital skin is reddish—darker than American and European Herring Gulls.

Vega Gull, showing brownish eye with reddish orbital skin. (Frank Rendon Park, Daytona Beach, Florida; March 1, 2017.) © Paul Hueber

Vega Gull, winter adult. (Half Moon Bay, California; December 8, 2021.) © Malia DeFelice

Adult Vegas in winter plumage often show extensive streaking around the neck—forming a “necklace”—and sometimes have noticeable streaking on the head and dark shadows around the eyes. The amount of head-streaking varies individually, but seems to average less than on American and European Herring, but more than Mongolian and “Taimyr” Gulls.

Vega typically enters winter plumage in September and goes back into breeding plumage around March.

Vega Gull, winter adult entering breeding plumage, with an American Herring Gull partly visible at the right. (Frank Rendon Park, Daytona Beach, Florida; March 1, 2017.) © Paul Hueber

Vega Gull, winter adult showing extensive dark streaking around the neck. (Salisbury, Maryland; January 2, 2009.) © Tom Johnson

Immature Plumages. As in other Herring Gulls, juvenile Vegas are brown with bold spots on the mantle and wing coverts. The bold spots usually wear off in September, leaving the upperparts pale-brown with narrow chevrons and anchors on most first-winter and first-summer birds.

Vega Gull, juvenile. (Southeast Farallon Island, California; October 7, 2014.) © Dan Maxwell

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Point Pinos, California; January 16, 2018.) © Blake Matheson

On the spread wing, first-year Vegas show the typical Herring Gull pattern: blackish primaries, primary coverts, and secondaries, with a distinctly paler “window” on the inner primaries.

Vega Gull, juvenile or first-winter. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 20, 2016.) © Cory Gregory

Vega Gull, juvenile. (Gulf of Anadyr, Russia; September 12, 2016.) © Christophe Gouraud

The tail feathers are mostly dark—varying from blackish to pale shades of brown. The rump, uppertail coverts, and the bases of the outer tail feathers are mostly pale with dark barring (resembling European Herring, unlike American Herring).

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Half Moon Bay, California; January 20, 2016.) © Alvaro Jaramillo

Vega Gull, first-summer. (Nome, Alaska; July 15, 2016.) © Bryce Robinson

Subadult Plumages. Subadults follow the typical progression of four-year gulls, replacing the mottled brown feathers of the wings and mantle with definitive gray feathers from the second winter molt into the third summer.

Notes

Monotypic species or form, of unsettled status. Genetic analyses indicate that vegae likely diverged from all other current gull populations more than two million years ago (Černý & Natale 2021)—longer ago than most widely accepted species within Larus—which appears to provide strong support for recognition of the Vega Gull as a separate, monotypic species.

Traditionally considered conspecific with the European Herring Gull (argentatus), American Herring Gull (smithsonianus), and various other forms, known collectively as the Herring Gull (argentatus). Starting around the 1990s, gull experts have increasingly recognized Vega as a separate species, or alternatively considered it to be conspecific with the Mongolian Gull (mongolicus), with the two together known as the Vega Gull (vegae), or conspecific with both Mongolian and American Herring, and known collectively as the Arctic Herring Gull (smithsonianus).

See below for comparisons of the Vega Gull with American Herring, Mongolian, and “Taimyr” Gulls.

Cf. American Herring Gull. Vega and American Herring Gulls have traditionally been regarded as conspecific, either as subspecies of the global Herring Gull or as the principal Asian and American components of the Arctic Herring Gull. They occur together regularly in western Alaska, and both have been found wandering much farther into one another’s ranges. This certainly occurs much more often than the records indicate, as the two forms are very similar and even well-observed individuals may be impossible to identify in the field.

Mantle Color: Their breeding plumages are essentially identical except that Vega’s mantle averages slightly darker than American Herring’s. Sometimes this difference is noticeable when the two occur together, which has resulted in some detections of Vega Gull in North America.

Eyes and Orbital Skin: The American Herring Gull has pale-yellow eyes surrounded by somewhat pale orangish orbital skin. Vega Gull has much darker, reddish orbital skin, and its eyes vary from pale-yellow to brown.

Leg Color: Both Vega and American Herring Gull have pink legs. Vagrant Vegas found in North America sometimes appear to have deeper pink legs than the American Herring Gulls that they flock with, but this does not seem to be a reliable distinction.

American Herring Gull (foreground) with Vega Gull—note the differences in the gray tone on the mantle, eye color (darker on this Vega), and orbital skin (red on Vega, pink on American Herring). (Frank Rendon Park, Daytona Beach, Florida; March 1, 2017.) © Paul Hueber

Vega Gull (center) among American Herring Gulls—note this Vega’s slightly darker mantle amid variation in the mantle colors of the gulls around it. (Half Moon Bay, California; December 8, 2021.) © Malia DeFelice

Head and Neck Streaking (Nonbreeding): In winter plumage, both Vega and American Herring Gull develop variable dark streaking and blotches on the head and neck. Vega often shows proportionately more streaking on the neck, whereas American Herring tends to show more extensive dark streaking on the head—a tendency that has resulted in some detections of American Herring in Asia. However, this streaking is too variable to be a basis for confirming identification.

Juvenile Coloration: Juveniles of both forms vary widely in their coloration, but American Herring Gull tends to be much darker overall—often dark, chocolate brown, whereas juvenile Vega Gulls are pale-brown overall. This difference becomes less pronounced as they progress into first-winter plumage. American Herring Gulls tend to become paler on the head first, which can help in some identifications.

Rump and Tail Coverts (Immature): First-winter and first-summer Vega and American Herring Gulls appear to differ consistently in their rump and tail patterns. First-year American Herrings tend to have an all-dark tail and heavily barred rump and tail coverts. First-year Vegas are pale-brown on the rump, tail coverts, and the base of the outer tail feathers, with finer barring.

Cf. Mongolian Gull. Together, the Vega and Mongolian Gulls comprise the East Asian contingent of what was once globally known as the Herring Gull. In recent years, Mongolian (mongolicus) has been classified variously as an independent species or as a subspecies of Caspian (cachinnans), Vega (vegae), Arctic Herring (smithsonianus), or Herring (argentatus) Gull. Most taxonomic authorities still classify Vega and Mongolian as conspecific—but genetic analyses and differing life histories indicate that they are at least distinct forms. Their breeding ranges are widely separated: Mongolian breeds on lakeshores deep in the Asian interior at temperate latitudes, whereas Vega breeds on the tundra of northeastern Siberian. In migration and winter, they overlap widely along East Asian coasts from the Sea of Japan to Taiwan and Hong Kong—although the overlap is limited by habitat preferences, as Mongolian tends to favor lakes and estuaries, whereas Vega is more strictly coastal.

Physical differences between Vega and Mongolian are subtle and variable, depending on life-stage and season. Immatures are more readily identifiable than adults. Many individuals require multiple factors to identify, and some are borderline cases that cannot be confidently assigned to one or the other.

Wingtip Pattern: Adult Mongolian typically has more extensive black on the wingtips, forming an almost-complete triangle with two narrow pale tongues projecting into it. The black on Vega’s wingtips typically appears more like a V, solid on the leading edge and broken on the trailing edge, with a mostly gray area in between, usually with white “moons” or a “string of pearls” between the gray and black. (Note, however, that wingtip patterns are not entirely consistent, as some Mongolians have less extensive black than average, and have approximately the typical Vega pattern, including the string of pearls.)

Mongolian Gull in nonbreeding plumage, showing nearly complete black triangle on the wingtips and typically sparse streaking on the nape. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 18, 2022.) Anonymous

Vega Gull in nonbreeding plumage, showing V-shaped black wingtips with “string of pearls” (white spots between the gray and black in the wingtips), and extensive streaking on the head and neck. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 18, 2022.) Anonymous

Leg Color: Adult Mongolian’s legs vary from yellowish to dull orange to pink. Vega’s legs are more consistently pink—and usually more vivid than Mongolian’s. (Note that there are reports of Vega Gulls with yellowish legs, but such individuals appear to be exceptional and some of the reports may result from confusion among Mongolian, Vega, and “Taimyr” Gulls.)

Mantle Color: Vega’s mantle averages somewhat darker gray than Mongolian’s. There is enough variation within Vega that the tone of gray is an inconsistent feature for identification, but many Vegas stand out as dark, and Mongolians generally do not.

Head and Neck Streaking (Nonbreeding): Adults in winter plumage differ in the usual amount and distribution of dark streaks on the head and neck. Many Vega Gulls show extensive streaking all around the neck—forming a necklace—and often have noticeable streaking on the head. Mongolian typically has a partial collar of streaks on the nape, but usually remains clean white on the head and front of the neck. However, the amount of streaking varies widely in both, so this field mark is suggestive but not reliable.

Molt Timing: Mongolian Gull begins nesting in April, almost two months earlier than Vega, and accordingly enters breeding plumage earlier than Vega. Mongolians typically attain their clean, crisp breeding plumage by February, whereas Vegas molt in March and April.

Vega Gull, juvenile, showing mostly black tail with barring on the rump, uppertail coverts, and base of the outer tail feathers. (Southeast Farallon Island, California; October 7, 2014.) © Dan Maxwell

Mongolian Gull, juvenile, showing black tail-band, white rump and uppertail coverts, and fine barring on the base oof the tail. (Khar-Us Lake, Hovd, Mongolia; October 6, 2019.) © Silas Olofson

Rump and Tail Coverts (Immature): First-year Vega and Mongolian Gulls—from juvenile to first-summer plumages—appear to differ consistently in their rump and tail patterns. First-year Vegas tend to show a wider dark tail-band and more dark barring on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers. First-year Mongolians are mostly white on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers, with sparse, thin barring, and tend to show a narrower but darker tail-band. (Both can be black, but Mongolian’s is consistently blackish, whereas Vega’s varies from pale-brown to blackish.)

Cf. “Taimyr Gull”. The “Taimyr Gull” has been dismissed as a hybrid between Heuglin’s and Vega Gulls, but there are indications that it is a genetically distinct population with its own life history and migratory pattern—as the only member of the Lesser Black-backed Gull complex that winters on the Pacific. Whether of hybrid origin or not, and regardless of its taxonomic validity, the “Taimyr Gull” creates a difficult identification puzzle where it overlaps with the Vega Gull. The area of overlap apparently includes a large portion of Asia’s Pacific coasts and islands, from the Sea of Okhotsk to the South China Sea, where both occur during migration and winter. The extent of their overlap is poorly understood in part because they are so similar and identification criteria are poorly understood.

Leg Color: The majority of adult Vega Gulls show clearly pink legs and the majority of adult “Taimyr Gulls” show clearly yellow legs—so leg color can be a reliable clue to identification in many cases, but it is not always definitive. Confusingly, both populations reportedly include minorities with the other leg color, resulting in a spectrum of pink- and yellow-legged adults. It may be more accurate to describe both populations as including a minority of “orange-legged” individuals that can appear either yellowish or pinkish depending on lighting and other factors. (It also seems possible that at least some observations of unexpected leg color—i.e., pink in “Taimyr” or yellow in Vega—could be due to misidentification based on faulty assumptions, in light of their general similarity and geographical overlap.)

Wingtip Pattern: “Taimyr” typically shows more extensive black on the wingtips, forming a nearly complete triangle with two narrow gray tongues, and lacking white subterminal spots between the black and gray portions of the primaries. The black on Vega’s wingtips typically appears more like a V: solid on the leading edge and broken on the trailing edge, with a mostly gray area in between, usually with three white “moons” that form a “string of pearls” between the gray and black. However, the appearance of wingtip patterns varies individually, by molt-stage, and the spread of the wing, so even well-established distinctions are not always clear or consistent—for example, when “Taimyr’s” primaries are newly grown in, they sometimes show whitish subterminal spots.

Vega Gull—note partial “string of pearls”: white subterminal spots between the gray and black in the wingtips. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; May 28, 2016.) © Liam Singh

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis—note the absence of white spots between gray and black in the wingtips. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 10, 2021.) Anonymous

Mantle Color: Although the adult mantle color of both forms can be described as medium-gray, “Taimyr’s” averages somewhat darker than Vega’s. There seems to be enough variation within both—as well as uncertainty about the full extent of that variation—to make this difficult to apply consistently, but some portion of the “Taimyr” population appears noticeably darker than all Vegas (such that “Taimyr” appears closer to the typical coloration of Slaty-backed). Circumstantial factors such as feather age, feather-wear, sun-bleaching, and lighting can complicate comparisons of such similar shades of gray, so mantle color tends to be more indicative than conclusive.

Vega Gull (left) with “Taimyr Gull”, both second-winter birds—very similar, but note “Taimyr’s” cleaner white head and neck. (Mai Po Nature Reserve, Hong Kong; March 21, 2021.) © Matthew Kwan

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, first-winter—note lack of pale “window” on inner primaries. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 10, 2021.) Anonymous

Molt Timing: The key difference used to support identifications of many “Taimyr Gulls” away from their breeding grounds is molt timing, which aligns with that of Heuglin’s rather than Vega. According to the molt-sequence information provided by Olsen & Larsson (2003), Heuglin’s retains its juvenile plumage two to three months longer (until November-December versus September), then both molt back into their summer plumages at approximately the same time (in March-April), but Heuglin’s keeps its summer plumage for about two months longer each year (until October versus August). So “Taimyr” and Vega Gulls may be detectably out of synch from approximately August or September until mid-winter—during a substantial portion of each year when they occur together along East Asian coasts.

More Images of the Vega Gull

Vega Gull, breeding adult—with a pale-yellow eye but dark reddish orbital skin. (Anadyr, Chukotka, Russia; July 9, 2018.) © Martin Rheinheimer

Vega Gull. (Beppu, Oita, Kyushu, Japan; November 1, 2009.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Vega Gull, winter adult, with “Taimyr” and Black-tailed Gulls in the background. (Beppu, Oita, Kyushu, Japan; November 1, 2009.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Vega Gull—with pale-yellow eye but dark reddish orbital skin. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 20, 2016.) © Cory Gregory

Vega Gull, winter adult, among American Herring Gulls. (Half Moon Bay, California; December 8, 2021.) © Chris Hayward

Vega Gull, winter adult. (Brownsville Landfill, Texas; February 21, 2015.) © Willie Sekula

Vega Gull. (Nome, Alaska; May 22, 2013.) © Ian Davies

Vega Gull, winter adult. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; February 27, 2021.) Anonymous

Vega Gull, winter adult. (Salisbury, Maryland; January 2, 2009.) © Tom Johnson

Vega Gull in worn breeding plumage. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 8, 2021.) © Buzz Scher

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Cape Nosappu, Nemuro, Hokkaido, Japan; December 27, 2013.) © Ian Davies

Vega Gull, juvenile. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 20, 2016.) © Cory Gregory

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Point Pinos, California; January 16, 2018.) © Blake Matheson

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Point Pinos, California; January 16, 2018.) © Blake Matheson

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Mai Po Nature Reserve, Hong Kong; March 21, 2021.) © Matthew Kwan

Vega Gull, first-summer. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, Alaska; September 2, 2021.) © Buzz Scher

Vega Gull, first-summer. (Nome, Alaska; July 15, 2016.) © Bryce Robinson

Vega Gull, juvenile or first-winter. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 20, 2016.) © Cory Gregory

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Point Pinos, California; January 16, 2018.) © Blake Matheson

Vega Gull, first-winter. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; March 2, 2021.) Anonymous

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International. 2019. Larus smithsonianus (amended version of 2018 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T62030590A155596462. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T62030590A155596462.en. (Accessed February 7, 2022.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

Cerný, D., and R. Natale. 2021. Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes). bioRχiv preprint: http://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.15.452585v1.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed February 7, 2022.)

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Howell, S.N.G., and J.L. Dunn. 2007. Gulls of the Americas. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Moores, N. 2011. Taimyr Gull Larus (heuglini) taimyrensis: an Update. BirdsKorea. http://www.birdskorea.org/Birds/Identification/ID_Notes/BK-ID-Taimyr-Gull.shtml.

Olsen, K.M., and H. Larsson. 2003. Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

van Dijk, K., S. Kharitonov, H. Vonk, and B. Ebbinge. 2011. Taimyr Gulls: evidence for Pacific winter range, with notes on morphology and breeding. Dutch Birding 33:9-21.

Xeno-Canto. 2022. Vega Gull – Larus vegae. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Larus-vegae. (Accessed February 7, 2022.)