Frontiers of Taxonomy: Preserve the Black-capped Petrel

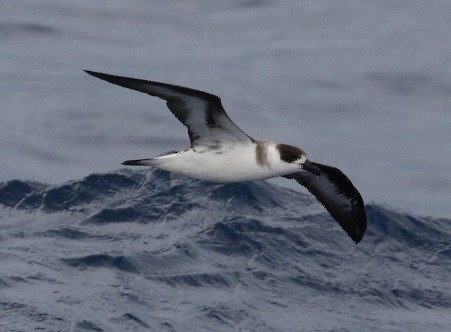

Black-capped (“White-faced”) Petrel © Peter Flood

In their 2019 book, Oceanic Birds of the World, Steve Howell and Kirk Zufelt provisionally recognize two species of Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata), which they dub “White-faced” (hasitata) and “Black-faced” (sp. nova). This treatment is based on indications that the lighter- and darker-faced petrels might represent separate populations that do not interbreed. The strongest evidence for this conclusion is a reportedly consistent difference in mitochondrial DNA markers, which seems to establish that the Black-capped Petrel includes distinct lineages that have not recently interbred.

The story remains confusing, however, because the two forms overlap widely in appearance and distribution. The overlaps are extensive enough that it is difficult to draw any line between them—either visible or geographical—and there is room to doubt that they are distinguishable forms or even discrete populations. Ongoing research and the accumulation of observations may eventually supply evidence that would enable us to reassess the internal taxonomy of P. hasitata. To be useful, such evidence would have to provide a basis to distinguish the forms by either field identification or geography:

“Black-faced Petrel,” at the black end of the spectrum. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 26, 2017.) © Irvin Pitts

“White-faced Petrel,” at the white end of the spectrum. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 29, 2019.) © Peter Flood

The Field Identification Problem: Intermediate Plumages: Black-capped Petrels show a wide spectrum of variation in key plumage features, especially the amount of black on the head. The palest individuals (“White-faced”) have an all-white face with a very limited black cap, and the darkest (“Black-faced”) have a full black helmet, while most appear to be somewhere in between, closer to the middle than to either extreme.

“Black-faced Petrel,” at the black end of the spectrum, with heavy gray partial collar. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 25, 2017.) © Steve Calver

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 24, 2019.) © Michael Todd

“White-faced Petrel,” typical plumage. (Offshore from Cape May, New Jersey; September 18, 2016.) © Jesse Amesbury

As a general rule, but with many exceptions, the extent of black on the head correlates to three other features: (1) a narrow or wide white collar on the nape; (2) a dark spur or partial collar on the side of the neck and chest; and (3) a wide or thin black carpal bar on the underwing. The clearest examples of “White-faced” have a small black cap, mostly white face, broad white nape collar, little or no dark gray on the side of the neck or chest, and a thin black carpal bar on a mostly white underwing. Conversely, the clearest examples of “Black-faced” have a large black helmet, mostly black face, narrow white nape collar (or, in rare cases, an all-dark nape), broad dark gray partial collars on the sides of the neck and chest, and a narrow white underwing lining bordered by a wide black carpal bar and black trailing edge.

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 20, 2008.) © Brian Sullivan

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate (or pale “Black-faced”?). (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; July 26, 2014.) © Nick Pulcinella

However, many individuals encountered in the field appear intermediate in some or all of these features. Judging from the hundreds of photographs published online, the “intermediates” could comprise the largest group and might be the majority, more numerous than the clear “White-faced” and “Black-faced” combined. Howell and Zufelt suggest that the “intermediates” could represent variation within one of the forms, or variation within both, or potentially a third form or species (call it “Middle-faced Petrel”?). The fundamental problem is that too much variation swallows the distinction. For any of the potentially diagnostic features, there appears to be a spectrum of clinal variation, with no clear place to draw a line of distinction.

In the mitochondrial DNA study (Manly et al. 2013), all of the specimens that the researchers deemed to be “intermediate” showed the same genetic markers as the “White-faced” specimens, whereas the “Black-faced” specimens were a discrete group. The significance of this result is difficult to interpret. It suggests that the “White-faced” population is diverse whereas the “Black-faced” is comparatively uniform. If this result is accurate and representative of the broader populations, it would affect field identification in a peculiar way: making “Black-faced” difficult to confirm. (The basic reasoning is this: “White-faced” would include all of the pale and “intermediate” individuals, so that form is highly variable. If so, it may also include some “dark” individuals. Now, are any observations of “Black-faced” still reliable?)

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 24, 2019.) © Michael Todd

The Geography Problem: No Separation: Currently available information provides no basis to distinguish the proposed “White-faced” and “Black-faced” forms geographically. This is peculiar because geography is usually the easiest basis to differentiate closely related, similar species. Speciation usually results from a geographical separation of populations, which prevents interbreeding and allows genetic drift to differentiate the population. Without geographical separation, interbreeding tends to occur and prevent the genetic drift needed for speciation—so a theory of separation (usually geographical) is fundamental to a distinction between closely related. Curiously, however, the Black-capped Petrel “complex” lacks a theory of geographical separation that correlates to the two recognized forms.

Black-capped Petrels are extremely difficult to observe on their breeding grounds. They nest on remote, steep mountain slopes, where their activity is nocturnal, and they are rarely seen clearly enough to distinguish “White-faced” from “Black-faced” from “intermediates.” The locations of their breeding grounds are not fully known—new ones have been discovered in the 2000s, and some sites are suspected but uncertain. Currently, four breeding colonies (all on Hispaniola) have been confirmed, at least two more are near-certain (on Cuba and Dominica).

With at least six nesting areas on at least three islands, the breeding range of P. hasitata is obviously large enough to accommodate multiple populations. So, which form/population nests on which island(s)?

Howell and Zufelt note that “White-faced” presumably nests on Dominica and possibly elsewhere in the Caribbean, and that “Black-faced” nests on Hispaniola. But the hypothesis that “White-faced” is Lesser Antillean and “Black-faced” is Greater Antillean does not comport with the (concededly scant) available evidence.

“Black-faced Petrel,” typical plumage. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 25, 2017.) © Tom Benson

“Black-faced Petrel,” at the dark end of the spectrum. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 29, 2019.) © Frank Hawkins

“Black-faced Petrel,” typical plumage. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 7, 2018.) © Brian Sullivan

“Black-faced Petrel,” lacking a white nape. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 20, 2008.) © Brian Sullivan

Published photographs from Hispaniola show what appear to be both “White-faced” and “Black-faced”: e.g., a photograph of an individual killed by fire, apparently at Morne Vincent in southeastern Haiti, is unambiguously “White-faced” (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2018); and a photograph from a burrow at Morne Vincent shows a fledgling and adult that both appear to be “Black-faced” (Simons et al. 2013)—although this identification could be inconclusive, as discussed above. Photographs of birds that collided with structures on Hispaniola show apparently “intermediate” individuals (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2018). Meanwhile, sightings around a likely Cuban breeding site have been attributed to “the pale morph” (which, if accurate, must refer to the “White-faced” form).

This mixture is not surprising in light of the basic accounting of observations. As discussed above, most observations away from breeding areas are attributed to “White-faced” (especially if this form truly includes most or all “intermediates”) but the vast majority of Caribbean observations and all of the confirmed breeding sites are in the Greater Antilles, and there are few recent observations in the Lesser Antilles (most of which are likely but unconfirmed radar detections over Dominica). The numbers of observations at sea and at or near the breeding areas suggests that both forms nest in the Greater Antilles, and the photographs indicate that they overlap on Hispaniola.

“White-faced Petrel,” typical plumage. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 8, 2018.) © Brian Sullivan

“White-faced Petrel,” at the white end of the spectrum. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 29, 2019.) © Peter Flood

Alternative Explanation: A Merger of Two Forms: The 2013 genetic study found evidence for a long-term divergence of two populations. However, that divergence does not appear to correlate with an ascertainable difference between separable forms, nor with a specific geographical division. One possible, but inconspicuous explanation is that the history of the Black-capped Petrel may have taken a recent twist that has led long-diverging populations to merge.

During the colonial period, human populations on Guadeloupe and Dominica hunted nesting petrels to the point of eradication (or perhaps only near-eradication on Dominica). It seems likely that many of the initial survivors lost their mates, and perhaps some portion of them wandered and eventually paired with members of the Hispaniolan and Cuban populations. This is purely speculative, of course, but it would account for the detected differences in sampled specimens (a legacy of prior divergence) and the apparent inseparability of modern populations

Our current information about the Black-capped Petrel is patchy, skewed toward observations at a few locations. It is obviously not sufficient to answer every question. The status of “White-faced” and “Black-faced” Black-capped Petrels as possibly discrete populations, forms, or species, will likely remain speculative unless differing appearances can be distilled to visible identification criteria correlated with different breeding areas. Until that or other clarifying information becomes available, there seems to be no basis to subdivide the Black-capped Petrel.

References

Howell, S.N.G., and K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press.

Manly, B., B.S. Arbogast, D.S. Lee, and M. van Tuinen. 2013. Mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals substantial population structure within the Endangered Black-capped petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). Waterbirds 36:228-233.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Black-capped petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). Version 1.0. April 2018. https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/156416. Atlanta.

Text © Russell Fraker / July 25, 2020