Birdfinding.info ⇒ The eastern, high Arctic form of Heuglin’s Gull is little-known and widely dismissed as a hybrid instead of a valid taxon—but the studies conducted thus far appear to support recognition, possibly as a distinct species. From late October to late March, it can be found consistently in Hong Kong and Taiwan, where it may be the commonest large gull. During spring and fall migration, it becomes locally common in South Korea. Uncommon in winter in southern Japan, and apparently annual around Bangkok (e.g., Bang Pu Recreation Center).

“Taimyr Gull”

Larus heuglini taimyrensis

Breeds in northern Siberia; winters along Pacific coasts of Asia.

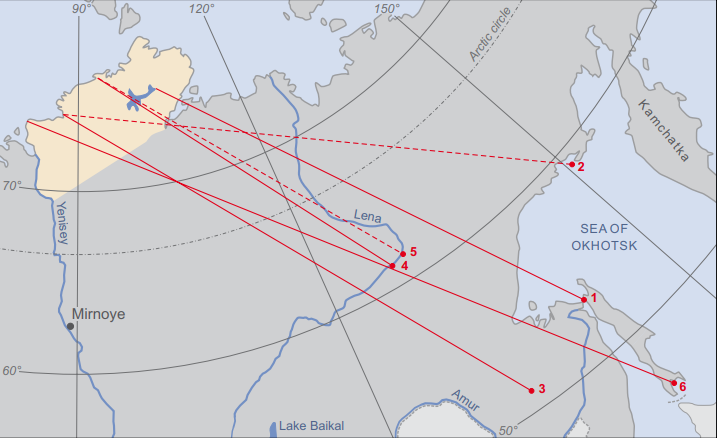

Approximate breeding range and overland migration route of the “Taimyr Gull”, with red lines connecting the locations where six individuals were banded on the Taimyr Peninsula to sites where they were detected during migration. © K. van Dijk et al. 2011

Breeding. Nests on the Taimyr Peninsula in northern Siberia, “in colonies on islands along the coast, in inland areas along rivers and near lakes with islands and rocky outcrops, and in low densities on the tundra near small ponds” (van Dijk et al. 2011).

In 1992, the total population was estimated at 10,000-12,000 pairs, with the largest colonies on islands near Mys Vostochny (~2,500 pairs) in the western Taimyr, and at the mouth of the Nizhnyaya Taimyra River (~1,200 pairs) in the northern Taimyr. Additional sites where smaller colonies have been noted include Medusa Bay, Middendorf Bay, and Pronchishcheva Lake.

Nonbreeding. The winter range is poorly understood due to identification challenges, but appears to comprise coastal waters from the Korean Peninsula and southern Japan south to southern China, Hainan, and Taiwan, with the majority of the population apparently wintering along the southern coast of China.

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, in the largest breeding colony. (Mys Vostochny, Taimyr, Russia; July 13, 2007.) © Gerard Müskens

Small numbers have been found regularly farther south at a few sites in Southeast Asia, especially around the Gulf of Siam, and in the Philippines.

Movements. “Taimyr Gulls” begin to depart their breeding grounds in late July, but most remain until mid-August, when the juveniles have fully fledged. They apparently fly southeast across the interior of eastern Siberia toward the Sea of Okhotsk and Sakhalin, then reorient south or southwest toward the South China Sea. Southbound migrants have been noted arriving in South Korea in September and increasing into October, with small numbers remaining into November and overwintering.

Northbound departures from southern wintering areas apparently occur during March. Numbers in South Korea increase from March into April, and peak in late April. Most arrive on their breeding grounds by late May.

Few cases of long-distance vagrancy have been clearly documented and reported. Records of vagrants identified as taimyrensis, at least tentatively, include one photographed at sea in the Northwest Chain of Hawaii (128 km from Gardiner Pinnacles) on October 9, 2010, and one with ambiguously orangish legs that spent the winter of 2020-21 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia.

Identification

A confusingly intermediate gull that resembles several other members of the Lesser Black-backed and Herring Gull complexes. Some authorities consider it to be a hybrid population between adjacent populations of the two complexes: Heuglin’s (heuglini) to the west and Vega (vegae) to the east. Adult “Taimyr” typically differs from Vega in having yellow or yellowish legs, a slightly darker gray mantle (on average), and little or no white on the inner portion of the wingtips (i.e., no distinct “string of pearls”). Its mantle averages paler gray than on typical Heuglin’s.

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, in breeding plumage. (Bird Islands, Mys Vostochny, Taimyr, Russia; July 8, 1991.) © Jan van de Kam

Adult Plumages. Adults have a medium-gray mantle, usually darker than Vega and Mongolian (mongolicus), but paler than Slaty-backed (schistisagus).

“Taimyr’s” wingtips are extensively black, usually with a single white “mirror” near the tip of the outermost primary. The black on “Taimyr’s” wingtips typically forms a neat triangle on the spread wing, with two narrow gray tongues.

“Taimyr” usually lacks distinct white subterminal spots (i.e., little “moons” that form a “string of pearls” on many gull wings) between the gray and black in the primaries—but note that freshly grown primaries may briefly show narrow whitish spots, which can cause confusion.

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, showing typical wingtip pattern: a black triangle with two gray tongues and one large spot on the outermost primary. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; February 27, 2021.) Anonymous

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, spread wing of individual captured for banding study, showing single white “moon” on outermost primary. (Medusa Bay, Taimyr, Russia; June 25, 2001.) © Leon Peters

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, facial close-up of individual captured for banding study, showing red orbital skin and spotted iris. (Bird Islands, Mys Vostochny, Taimyr, Russia; July 22, 2008.) © Jim de Fouw

“Taimyr’s” irises vary from pale-yellow to olive-brown, and its orbital skin is reddish (like Vega).

Its legs are usually yellow, sometimes dull-yellowish, and in some cases either orangish or too dull to specify a color.

Adult “Taimyrs” in winter plumage usually show some dark streaking on the head and neck—sometimes pronounced and extensive, but usually less than on Vega and most other Herring-type gulls (but similar to Mongolian).

“Taimyr” typically enters winter plumage in November or December (synchronous with Heuglin’s, two months later than Vega) and goes back into breeding plumage in March or April.

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, with a relatively pale-gray mantle and yellowish-orange legs, entering nonbreeding plumage. (Beppu, Oita, Kyushu, Japan; November 1, 2009.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, still in breeding plumage in late fall. (Fukuoka, Kyushu, Japan; October 25, 2007.) © Peter Mackenzie

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, in nonbreeding plumage. (Guryongpo Beach, Kyongsangbuk-do, South Korea; January 24, 2021.) © Elizabeth Skakoon

Immature Plumages. As in other Lesser Black-backed and Herring-type Gulls, juvenile “Taimyrs” are brown with bold spots on the mantle and wing coverts. The bold spots usually wear off in October or November (later than Herring-types), leaving the upperparts pale-brown with narrow chevrons and anchors on most first-winter and first-summer birds.

On the spread wing, first-year “Taimyrs” show blackish primaries, primary coverts, and secondaries. The inner primaries often appear somewhat paler than the other flight feathers, but this “window” effect is usually less pronounced than on Vega and other Herring-type gulls.

The tail feathers are mostly black, whereas the rump, uppertail coverts, and the bases of the outer tail feathers are mostly pale with sparse barring—rapidly transitioning to white with little or no barring.

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, second-winter. (Mai Po Nature Reserve, Hong Kong; March 9, 2021.) © Bart De Schutter

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, third-winter. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 18, 2022.) Anonymous

Subadult Plumages. Subadults follow the typical progression of four-year gulls, replacing the mottled brown feathers of the wings and mantle with definitive gray feathers from the second winter molt into the third summer.

Notes

Monotypic form, of unsettled status, but the apparently growing consensus is to classify it as one of three distinct forms of Heuglin’s Gull (heuglini). Recognition of the “Taimyr Gull” as a formally described taxon remains controversial, as some gull experts have been skeptical of its validity, on the basis that it appears to be a localized population of hybrid origin, wedged between purer populations of Heuglin’s Gull to the west and Vega Gull (vegae) to the east, with features that are intermediate between those populations.

Despite its outward appearances of hybrid origin, van Djik et al. (2011) have presented a persuasive case that the “Taimyr Gull” shows objective indicators of being a genetically distinct, self-contained population with a unique life history, and possibly a separate species. The evidence includes a genetic analysis indicating that “Taimyr” is differentiated from other populations with no signs of recent introgression, and the fact that the “Taimyr” population appears to have a distinct migratory pattern—as the only member of the Lesser Black-backed Gull complex that winters on the Pacific.

The status of Heuglin’s Gull as a species or subspecies group also remains unsettled, as it has traditionally been considered conspecific with the Lesser Black-backed Gull (fuscus).

See below for comparisons of the “Taimyr Gull” with Vega, Mongolian, and “Steppe” Gulls.

Cf. Vega Gull. The “Taimyr Gull” has been dismissed as a hybrid between Heuglin’s and Vega Gulls, but there are indications that it is a genetically distinct population with its own life history and migratory pattern—as the only member of the Lesser Black-backed Gull complex that winters on the Pacific. Whether of hybrid origin or not, and regardless of its taxonomic validity, the “Taimyr Gull” creates a difficult identification puzzle where it overlaps with the Vega Gull. The area of overlap apparently includes a large portion of Asia’s Pacific coasts and islands, from the Sea of Okhotsk to the South China Sea, where both occur during migration and winter. The extent of their overlap is poorly understood in part because they are so similar and identification criteria are poorly understood.

Leg Color: The majority of adult Vega Gulls show clearly pink legs and the majority of adult “Taimyr Gulls” show clearly yellow legs—so leg color can be a reliable clue to identification in many cases, but it is not always definitive. Confusingly, both populations reportedly include minorities with the other leg color, resulting in a spectrum of pink- and yellow-legged adults. It may be more accurate to describe both populations as including a minority of “orange-legged” individuals that can appear either yellowish or pinkish depending on lighting and other factors. (It also seems possible that at least some observations of unexpected leg color—i.e., pink in “Taimyr” or yellow in Vega—could be due to misidentification based on faulty assumptions, in light of their general similarity and geographical overlap.)

Wingtip Pattern: “Taimyr” typically shows more extensive black on the wingtips, forming a nearly complete triangle with two narrow gray tongues, and lacking white subterminal spots between the black and gray portions of the primaries. The black on Vega’s wingtips typically appears more like a V: solid on the leading edge and broken on the trailing edge, with a mostly gray area in between, usually with three white “moons” that form a “string of pearls” between the gray and black. However, the appearance of wingtip patterns varies individually, by molt-stage, and the spread of the wing, so even well-established distinctions are not always clear or consistent—for example, when “Taimyr’s” primaries are newly grown in, they sometimes show whitish subterminal spots.

Vega Gull—note partial “string of pearls”: white subterminal spots between the gray and black in the wingtips. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; May 28, 2016.) © Liam Singh

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis—note the absence of white spots between gray and black in the wingtips. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 10, 2021.) Anonymous

Mantle Color: Although the adult mantle color of both forms can be described as medium-gray, “Taimyr’s” averages somewhat darker than Vega’s. There seems to be enough variation within both—as well as uncertainty about the full extent of that variation—to make this difficult to apply consistently, but some portion of the “Taimyr” population appears noticeably darker than all Vegas (such that “Taimyr” appears closer to the typical coloration of Slaty-backed). Circumstantial factors such as feather age, feather-wear, sun-bleaching, and lighting can complicate comparisons of such similar shades of gray, so mantle color tends to be more indicative than conclusive.

Vega Gull (left) with “Taimyr Gull”, both second-winter birds—very similar, but note “Taimyr’s” cleaner white head and neck. (Mai Po Nature Reserve, Hong Kong; March 21, 2021.) © Matthew Kwan

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, first-winter—note lack of pale “window” on inner primaries. (Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 10, 2021.) Anonymous

Molt Timing: The key difference used to support identifications of many “Taimyr Gulls” away from their breeding grounds is molt timing, which aligns with that of Heuglin’s rather than Vega. According to the molt-sequence information provided by Olsen & Larsson (2003), Heuglin’s retains its juvenile plumage two to three months longer (until November-December versus September), then both molt back into their summer plumages at approximately the same time (in March-April), but Heuglin’s keeps its summer plumage for about two months longer each year (until October versus August). So “Taimyr” and Vega Gulls may be detectably out of synch from approximately August or September until mid-winter—during a substantial portion of each year when they occur together along East Asian coasts.

Cf. Mongolian Gull. While the “Taimyr Gull” is most closely associated with Vega Gull due to their extensive geographical overlap and similar adult plumages, “Taimyr” also overlaps widely with the Mongolian Gull, and the share several features in common. Both have more southerly winter ranges overall than Vega, both migrate inland across parts of eastern Asia (which Vega is not known to do), both typically have yellowish legs (unlike Vega), both have more complete black triangles on their wingtips than Vega, and their immature plumages are more similar to one another than to Vega’s.

Mantle Color: The “Taimyr Gull’s” mantle is typically a darker shade of gray than that of any of the Herring-type gulls. Vega is the darkest of the Herring group, so it is the closest to “Taimyr’s” typical coloration. In most cases, Mongolian would be noticeably paler and “Taimyr” noticeably darker. Mantle color is often the most immediate factor in differentiating gulls, especially when they are seen together in the same lighting, so adult Mongolian and “Taimyr” may be most readily distinguished by their general coloration.

Molt Timing: The Mongolian Gull begins nesting in April, almost two months earlier than “Taimyr”, and accordingly tends to enter breeding plumage earlier. Mongolians typically attain their clean, crisp breeding plumage by February, whereas “Taimyr” goes through this molt in March or April. First-year “Taimyrs” hatch much later than Mongolians and generally retain their juvenile plumage two to four months later (until November-December versus August-September). Even allowing for wide individual variation within each population, in general, “Taimyr” and Mongolian Gulls should be detectably out of synch during much of the year.

Rump and Tail Coverts (Immature): First-year “Taimyr Gulls” have some features that are intermediate between Vega and Mongolian Gulls. First-year Vegas tend to show a wider dark tail-band and more dark barring on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers. First-year Mongolians are mostly white on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers, with sparse, thin barring, and tend to show a narrower but darker tail-band. Like Vega, first-year “Taimyrs” tend to show a wide dark tail-band, but more like Mongolian, the tail-band is consistently blackish and they typically show little barring dark barring on the rump, tail coverts, and outer tail feathers—though “Taimyr” retains its barring later into the fall and winter, so it may resemble Vegas whose molt is more advanced at the same time of year.

Cf. “Steppe Gull”. “Taimyr” and “Steppe” Gulls are both widely suspected of having descended from Heuglin’s Gull through a history of hybridization with other populations—Vega (vegae) and Caspian (cachinnans) Gulls, respectively. Both are difficult to identify with confidence outside of the core areas where each is known to occur regularly. In general, “Taimyr” breeds in the high arctic and winters along Pacific coasts of East Asia, whereas “Steppe” breeds in central Asia and winters along Indian Ocean coasts of southwestern Asia. They are not known to overlap, but both have sometimes been suspected of occurring on the other’s wintering grounds, and records from Southeast Asia and Europe are difficult to evaluate without a geography-based presumption.

Identification criteria for both “Taimyr” and “Steppe” remain imperfectly understood, but a few factors appear to be clear enough to be useful in resolving some ambiguous cases.

Nonbreeding Adult Bill Pattern: In winter, adult “Steppe” typically develops a partial black ring near the tip. This seems to be unknown in “Taimyr”, so its presence may be diagnostic of “Steppe”.

Nonbreeding Adult Head Pattern: In winter, adult “Taimyrs” typically develop dark streaks on the head and neck, mostly on the nape, but often a full necklace and sometimes on the head as well. “Steppe” rarely develops substantial streaking—perhaps only in subadults or in the transition to definitive adult plumage (i.e., third- and fourth-winter plumages), and it is typically limited to fine streaks on the nape.

“Steppe Gull”, L. h. barabensis, in nonbreeding plumage, showing black ring near the tip of the bill and fine streaks on the nape. (Abu Dhabi, U.A.E.; November 14, 2019.) © Bird Explorers

“Taimyr Gull”, L. h. taimyrensis—a notably pale-mantled individual identified by the observer as taimyrensis, early in the transition into nonbreeding plumage, with streaks beginning to appear on the head and no black on the bill. (Beppu, Oita, Kyushu, Japan; November 1, 2009.) © Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

Wingtip Pattern: Although their wingtips probably do not differ consistently enough for reliable identification, one fairly consistent difference is the extent of their white “mirrors.” “Taimyr” typically has a single white mirror near the tip of the outermost primary (P10), whereas “Steppe” usually has the P10 mirror plus a smaller white spot adjacent to it on the next primary (P9).

Adult Mantle Color: On average, “Taimyr” tends to appear darker-gray than “Steppe”; however, both vary enough internally that the overlap between them might effectively overwhelm the difference.

Adult Leg Color: “Steppe” has yellow legs. “Taimyr’s” legs are usually yellow, but sometimes orangish and reportedly pink in some cases.

“Steppe Gull”, L. h. barabensis—judging from the black markings on the bill, and supported by the small white mirror spot on P9 and the lack of streaking on the head and neck. (Chao Phraya Shipping Channel, Samut Prakan, Thailand; January 26, 2022.) © Andaman Kaosung

“Taimyr Gull”, L. h. taimyrensis, in nonbreeding plumage, showing heavy streaking on the nape and smudges on the head, lacking distinct black near the tip of the bill. (Aogu Wetlands and Forest Park, Dongshi, Chiayi, Taiwan; January 10, 2022.) Anonymous

Molt-Stage: “Steppe” arrives on its breeding grounds in late March and nests in April, whereas “Taimyr” arrives on its breeding grounds in late May and nests in June. The timing of their molts and the stages of seasonal feather-wear are therefore likely to differ by an average of about two months.

More Images of the “Taimyr Gull”

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, in nonbreeding plumage. (Goseong-gun, Gangwon-do, South Korea; March 17, 2021.) © Jugdernamjil Nergui

“Taimyr Gull”, L. f. taimyrensis, as identified by a consensus of experts, showing orangish legs that appeared either yellowish or pinkish in various photos. (New Glasgow, Nova Scotia; January 5, 2021.) © Ken McKenna

References

Babbington, J. 2013. Large Gull ID Help. Birds of Saudi Arabia. https://www.birdsofsaudiarabia.com/p/large-gull-id.html. (Accessed April 20, 2022.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed April 20, 2022.)

Moores, N. 2005. Steppe Gull barabensis in South Korea: A Step Closer To Identification? http://www.birdskorea.org/Birds/Identification/ID_Notes/BK-ID-Steppe-Gull.shtml.

Moores, N. 2011. Taimyr Gull Larus (heuglini) taimyrensis: an Update. BirdsKorea. http://www.birdskorea.org/Birds/Identification/ID_Notes/BK-ID-Taimyr-Gull.shtml.

Olsen, K.M., and H. Larsson. 2003. Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

van Dijk, K., S. Kharitonov, H. Vonk, and B. Ebbinge. 2011. Taimyr Gulls: evidence for Pacific winter range, with notes on morphology and breeding. Dutch Birding 33:9-21.